“Then, one day in very early January we found ourselves slipping and sliding around Hampstead Heath in the mud, with the low-lying sun blinding us as we talked about ourselves and our lives. Something about Rose’s good humour and bright mischief made me feel a certain kinship toward her.

“Within a week we were recording. Our work was exploratory. Two people asked questions of each other, and as a consequence the void became less yawning. Music was created, and these two voices in the songs became two people: Rose and I.”

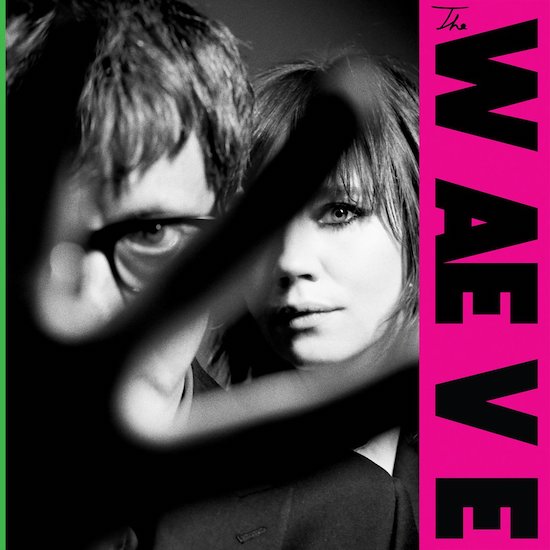

“Rose” is Rose Elinor Dougall, an indie-pop staple formerly of the Pipettes fame, with three solo albums released between 2010 and 2019. “I” is Graham Coxon, the indie, lo-fi side of Blur – among many other projects – writing about his newest music outlet, the Waeve, in his recent memoir, Verse, Chorus, Monster!. A new musical adventure deemed redeeming in light of the 2020 lockdown and subsequent social and human bewilderment

However, the duo’s self-titled debut is as far as possible from the covid-core tide that submerged the past couple of years’ music releases. It began as a remote exchange but quickly evolved into a close, in-person, personal and professional acquaintance. They discovered their mutual love for folk music and shared musings on their rough love for British cultural identity. They soon found themselves in Coxon’s home studio, with a finished album. The Waeve was born.

Listening to the self-titled debut record’s ten tracks gives the impression of watching two people fall in love in real life (as opposed to the way two people fall in love in a romantic film), beginning with their first, careful questions to each other and gradually progressing to the wilful construction of a new life together.

A path led by the track’s titles, starting from the opening ‘Can I Call You’, beating as fast as a heart approaching a new feeling, and ending with the sensual tenderness of ‘You’re All I Want to Know’.

“I’m not interested in the twee side of folk,” Dougall told NME. “We’re dealing with life and death and all that kind of thing. There’s a brutality to nature. It’s not all pastoral. Those are the visual things I feel that our music summons up.”

And there is blood pulsing all through the tracklist, empowering the smokey nightclub mood of Dougall’s voice over Coxon’s saxophone and warming Coxon’s raspy, high-pitched singing and sharp guitars as they encounter Dougall’s synth or piano lines. Their yearning for earnestness has been fulfilled with their songwriting, creating slow tunes that expose the duo’s scars, healed after life’s wounds.

The alchemy between the two musicians is palpable and electric. They couldn’t be further removed from the genres that made them famous – from pop’s gleaming, detached lights – and they fit in with confidence and raw honesty in this new environment. Finally, their long-desired quest for their true selves might have come to an end.