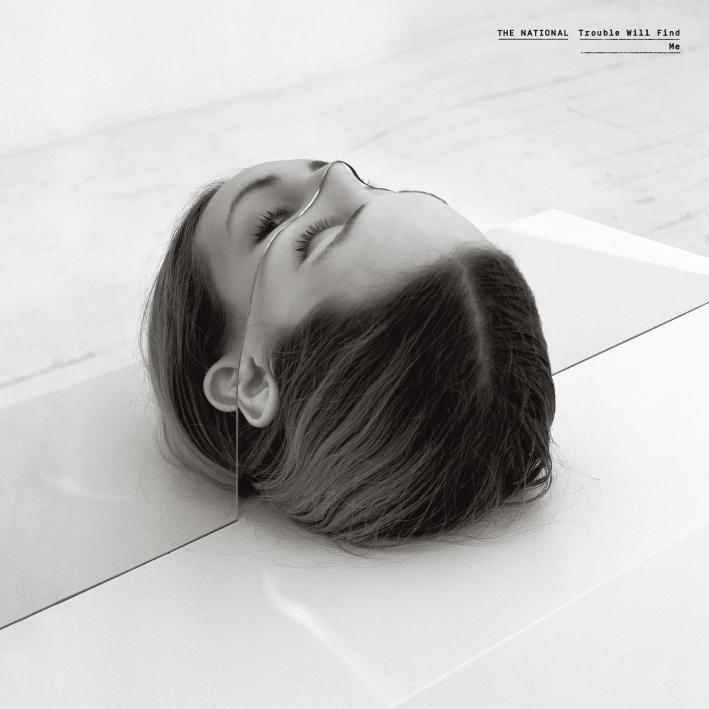

In 2010 The National went for broke with High Violet, and in the face of improbably high expectation, they pulled it off. The album – their fifth – took an exhausting two years to complete ("We fight over everything", explained guitarist Aaron Dessner in an interview with The Guardian), but by furnishing their songs with less streamlined, texturally dense arrangements, it thrust the Brooklyn-based quintet way up festival bills and end-of-year lists without sacrificing any of the weary, bruised romanticism that made them such a special prospect in the first place.

A 22-month world tour followed, which you imagine would have felt like an extended victory lap for the band, who had spent a decade gamely shaking off comparisons with their peers and gradually accumulating enough goodwill to be recognised purely on their own terms.

Not so. "We enjoyed it, but it was never easy," says singer, lyricist and bandleader Matt Berninger of the experience. "We always reminded ourselves that all of this is really fragile – that if we don’t deliver in, say, some festival show in Europe somewhere, we could start to slide."

Nevertheless, they were sufficiently emboldened by their success that Trouble Will Find Me came surprisingly quickly and easily. Berninger references their collective insecurities in the album’s accompanying press release, allowing that it wasn’t until after the High Violet tour that they were finally able to relax – "not in terms of our own expectations, but [because] we didn’t have to prove our identity any longer."

The group have long-eschewed reinvention in favour of a steady, satisfying progression that is evident from one release to the next and, with that in mind, their sixth LP succeeds precisely because it is what we have come to expect of The National at this point. Aaron and Bryce Dessner’s piano and guitar lines alternately weave delicate shapes around each other or come on with intuitive force, Bryan Devendorf’s drumming (likened, brilliantly, by filmmaker D.A.

Pennebaker to "rain falling through the leaves on a tree") is ceaselessly assured and inventive, and Berninger deploys his familiar baritone to stirring effect (though some of his best performances here arrive in a notably higher, brighter register). The record further shades the band’s sound by way of the fullest, most confident instrumentation they have yet put to tape, replete with strings, synth, woodwind and harmonies that spiral into haunting outros and unexpected breaks, and while the presence of some Sufjan Stevens-provided drum machines doesn’t exactly constitute a leap into unchartered waters, the Krautrock shimmer of ‘Humiliation’ and urgent pulse of ‘Sea Of Love’ showcase a group of musicians whose sense of adventure is very much alive.

Michael Stipe once suggested to the band that they needed to write a "pop song," and ‘I Should Live In Salt’ is feasibly the sound of his advice being taken to heart: all twinkling, ascending guitars set against a positively cavernous Devendorf beat. It is anchored, though, by a set of lyrics written about Berninger’s younger brother Tom, and the sibling relationship presumably explored at length in Mistaken For Strangers, a documentary the latter made in an ill-fated stint accompanying the band on tour. "I should leave it alone, but you’re not right," Berninger sighs, detailing the exasperation, affection and increasing concern he feels for his younger brother (lines that many, many siblings will be able relate to), before admonishing himself in the chorus: "I should live in salt for leaving you behind."

It makes for a big, emotional start to the record, albeit one immediately offset by the churning pitter-patter of ‘Demons’ and ‘Don’t Swallow The Cap’. Here and elsewhere, though, the gloom that underpins much of Berninger’s output is tempered with moments of levity. "We’ll all arrive in heaven alive," he asserts amid a stream of hazy non sequiturs in ‘Heavenfaced’, while he has rarely come on as directly as he does on ‘Fireproof’ or the gorgeous ‘Slipped’.

Perhaps not even the most ardent fan would have envisioned a song named ‘I Need My Girl’, but they will certainly recognise the sincerity which Berninger invests in the line here. Imagery taking in swamps, floods and ever-rising water levels continues to manifest itself in these songs, which are also strewn with references to friends, accomplices and iconic acts (a character named Jenny hovers in the background, echoing the presence of a Karen on 2005’s Alligator; Morrissey, Nirvana, Elliott Smith and The Beatles are all alluded to).

"Am I the one you think about when you’re sitting in your fainting chair, drinking pink rabbits?" Berninger asks in ‘Pink Rabbits’, evoking all manner of Fitzgeraldian heartache and excess. It is a gauzy, beautiful high point of an album not lacking for them; an intimate reflection on Los Angeles strung together by malaise and memorable lines. "You didn’t see me, I was falling apart / I was a television version of a person with a broken heart," he later notes. Yet, for all its weariness and sorrow, the song glimmers with a sense of affection and triumph; of a battle or love or ideology that was – and is – worth fighting for.

In an interview with Canada’s Q TV a few years ago Berninger conceded a tendency to dwell on dark themes (song titles like ‘Graceless’, ‘Demons’ and ‘Humiliation’ more or less speak for themselves), but also expressed the belief that his band’s songs contain a "pretty healthy balance between tenderness, optimism, humour and melodrama." The National have arguably never struck that balance quite as sweetly or persuasively as they do on Trouble Will Find Me, a layered, resoundingly human work that extends their winning streak without so much as breaking a sweat.