Despite the worn out idiom that Americans just don’t do self-deprecation, there’s a slab of US-born culture that has grown fat off its ability to look at itself in a scathing manner. In recent years, a strain of bands have mutated from the vapid ooze of skate punk, leaving behind the endless summer of American Pie and keg parties, and have grown up in an America of vastly disparate wealth and social opportunities. Blue-collar America, squatting behind the zirconian glitz of the States’ coastal wealth, got lost somewhere in youthful utopia of the millennium and the tubby consumerist media that came grunting out of it. Punk rock, its origins formed in the grit and subversion of 70s New York, was re-appropriated, its music turned into a fast, screaming celebration of America’s never-ending party.

Around 2007, when all of the wheels came falling off the supposedly invincible financial machine and the party abruptly ground to a halt, frat-boy rock started to sound archaic, tired, and horribly ill-suited to a country that had just had its banking industry disembowelled. For bands like Make Do and Mend, Cheap Girls and The Menzingers, acts that moreover focussed on the day-to-day grind of living as opposed to the anarchic gild of Against Me!, punk, once more, became about justified anger at dazzling unfairness.

The Menzingers, over their four album career, have made no frills about what it is to creep towards the dependencies and pressures of middle-age. Their albums, and most notably 2012’s magnificent On The Impossible Past, blaze with nostalgia and anger at their own inability to achieve, set deeply within a subversive Americana that smacks of Rad Bradbury or Stephen King. The diners and muscle cars, settings for the transient, hopelessly optimistic American personal quest, are instead receptacles for overripe dreams and disenchantment.

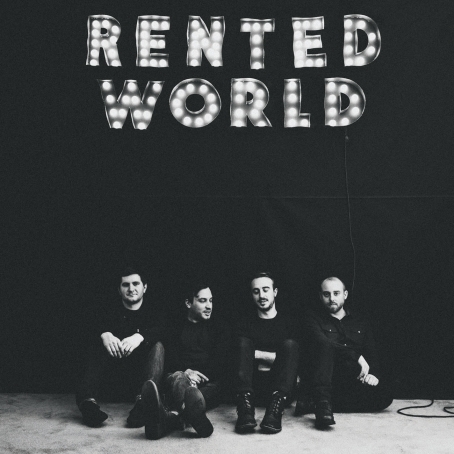

Rented World, their fourth full-length, initially seems like an extension of On The Impossible Past. Its settings are still the tired symbols of middle American capitalism, its subjects are buried in heartache, left wondering about the future and mortality, and always yearning for a time that’s now unreachable. Their ‘Rented World’, a phrase taken from a Philip Larkin poem about waking during that dark, still time just before dawn, is still too big for us all to understand; instead The Menzingers continue to seek out the snapshots of hope before our lease on this planet runs out.

Yet this album, for all of its sharp musicianship and the ever-brilliant play-off between vocalists Greg Barnett and Tom May, just doesn’t capture the gravity of its predecessor. This is partially due to the increased immediacy of the music, and in part down to the loss of lyrical nuance. It’s almost as if the band’s huge touring cycle after their last album prompted the fourpiece to swap in live-friendly heavier riffs for the ebb and flow of their deft lyric-led approach. The Menzingers of Rented World, as the almost banal opener ‘I Don’t Want To Be An Asshole Anymore’ proves, are much closer to the wasteful, fist-pumping punk of the early naughties.

The opening barrage, thankfully, doesn’t set the scene for the rest of the record. ‘Nothing Feels Good Anymore’ roils with thoughts of inadequacy and the dreamlike desperation of trying to run through molasses. The final two tracks, ‘Sentimental Physic’ and ‘When You Died’ are respectively the heaviest and softest tracks on the record, pitching fury against a Bob Dylan-like, distant meander through a deeply personal topic.

As the ending to Rented World goes to show, The Menzingers clearly haven’t lost the knack to talk universally in personal tones. The process behind this record is most likely the greatest cause behind the somewhat-tired themes that push Rented World away from the strength of its forebears, favouring an immediate sound that shuns the storytelling ebb and flow of what they’ve done before. However, for a band that’ve become the mouthpiece for a generation buried by expectation and social pressures, this album is a disappointment.