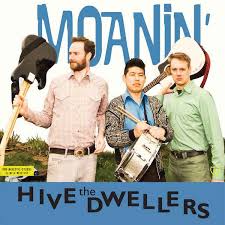

It would be impossible to cite every band and project Calvin Johnson ever got involved in since the early 1980s. Beat Happening, The Go Team, Dub Narcotic, Halo Benders… Calvin Johnson never stopped. For now, The Hive Dwellers (his latest band, formed in 2010) is all that matters. They are a rather elusive three-piece collective, with no stable line-up. Last April, Johnson was touring Europe to promote Moanin‘, their second album. He was traveling by himself, mostly by train, carrying with him a small acoustic guitar, one clean suit and a case brimming with K Records memorabilia.

Johnson stopped playing traditional venues a few years ago. I purchased Moanin‘ after he did a gig in the chapel of a private school, in Bordeaux, and spent the following days listening to the LP. It felt so incredibly, so absurdly alive. Moanin‘ is an album of nonchalant love songs and electric guitars, of sunny serenades and silly ecstasies. ‘Baby Be Mine’, the opening track, is one of Johnson’s more melodic moments. Over the years his voice has somehow mellowed, becoming less cavernous; it now has a tender, velvet patina to it. On ‘Baby Be Mine’ and ‘Love Will Come Back Again’, a woman – Lindsay Scheif – bemusedly sings along, echoing his every word. Her bright, clear voice makes Johnson’s seems even deeper by contrast. Every now and then, the roughness so characteristic of his earlier recordings suddenly surfaces again. ‘Moanin’ and ‘Daughters Of The Revolution’ are declamatory, unpolished preaching. They are closer to the bare, nearly-acapella style that Johnson developed on his solo albums.

The songs of The Hive Dwellers carry with them glistening echoes of early rock’n’roll. They have something of the magic energy of Buddy Holly, something of the beautifully raw, rapping racket of Eddie Cochran. The Hive Dwellers play straight, fast love songs with final twists. Moanin’ feels like childhood regained, mixed with a lingering taste of lemonade and heartbreak. Johnson mostly sings about relationships, journeys and the twisted geography of love. As Jonathan Richman before him, he is the poet of one city. His name and songs have become entirely entwined with the story of Olympia, the independent pop network and K Records (which he co-created with Candice Pederson in 1982). In ‘The Streets Of Olympia Town’, he describes the intricate, changing heart of the city.

Although they are charged with reminiscences and souvenirs, the ten songs of the album are more than autobiographical sketches. In the particular events of his own life, Johnson seems to be seeking broader, more general meanings. I like to think of his songs as small stages, continually traversed by characters absorbed in their own, everyday dramas.

What makes the songs so touching is not solely the simplicity of the recording (the minimal, direct warmth of the guitar, the primitive drum patterns, the defiantly lo-fi aesthetics) – but the palpable sense that The Hive Dwellers care deeply about what they play, and share their music unconditionally. Though he is cult figure, Johnson seems too impatient, too fretful, too undisciplined an artist to become a statue. He does not really look back. He plays old songs along with new ones; the past is within his music – he revisits ‘Love Will Come Back Again’, a song which was originally featured on his first solo album What Was Me – but it does not impede it. He keeps rewriting himself and, without fully reinventing anything, produces a music which is, at once, abruptly alive and untimely.