You get these people, don’t you, normally sort of pop-savvy without actually being ‘pop’ and very keen on iconoclasm, who really like to get their hardman on about the subject of youthfulness and endurance in music. As in, not benign "well you know, it’s for the kids really innit" type rhetoric but your grandstanding and frothy "ALL MUSICIANS OVER THIRTY SHOULD BE EXECUTED" throwdowns. The two that spring immediately to mind for me are the Manic Street Preachers and Ian Svenonius, especially when he was in his first band The Nation Of Ulysses. In both cases, the people involved have now been releasing records for at least twenty years without any long gaps. It’s almost as if the whole idea is built on sand and fails to hold up to scrutiny or, especially, the pleasures of finding yourself in a world where people give you metaphorical or literal blowjobs just because you’re you.

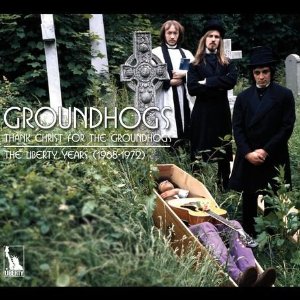

So yeah, the Groundhogs. If you listened to any/all of the five albums that are crammed into this three-CD remastered collection, without really knowing anything about the band, and someone told you that after 1972 they imploded in frazzled fury, never to make music again, and are now being fed mashed swede in a Gloucestershire care home in lieu of decent motor skills, that would seem pretty feasible, I think. This is totally not what happened, however: the Groundhogs, who formed in 1963, are still regularly touring now. You still chance on reports of how they energetically smash it as a live band, too. Technically they broke up in 1974 for a year, and not much went on from the late 70s to early 80s, and the band now is basically Tony McPhee (frontman and guitarist) plus a carousel of supplementary band members. But this crud sounds ELECTRIC in a fashion that goes way beyond just being blues played using electricity. It sounds damaged and speeding and sort of angry, but only because it knows life can bring great and profound joy (this is what I take from their famous album title Thank Christ For The Bomb); they sound counterculture because they were, even when they appeared on Top Of The Pops or toured with the Stones. I don’t know if this collection is aimed at old soaks who fancy re-sucking on their youth but can’t be shagged getting the LPs out of the attic, or younger and hyper-aware consumers of music who have glommed on to the fact the ‘Hogs get lauded as underground hero prototypes along the lines of Blue Cheer and Sir Lord Baltimore and a hundred ‘nother bands Julian Cope dickrides.

Got to say that the way the album tracks have been split (tragically, no pun intended) across the CDs is a bit of a fud. You get Scratching The Surface and side one of Blues Obituary on CD1; side two of Blues Obituary, Thank Christ For The Bomb and half of Split on CD2 and the rest of Split and Who Will Save The World? on the third coaster. If you found the clump of italics and capital letters that made up that sentence annoying to read, think what it’s gonna be like when you forget what the deal is here and unexpectedly have to walk across the room to change the CD so you can get ‘Cherry Red’ flamethrowing out of the speakers. It will suck! The irony is that half the time you were taking all that Mandrax that fucked up your short-term memory, it was at ‘happenings’ where the Groundhogs were on the bill. Wasn’t it? Okay, let’s move on if this doesn’t apply to you.

I don’t know of any infallible litmus test that bearded sorts might use to distinguish ‘blues’ from ‘blues-rock’, but on Scratching The Surface, the Groundhogs’ 1968 debut album, they move as much air as almost anyone else on the circuit at that time. A pretty big chunk of it are hand-me-down blues numbers, granted, but anyone decrying Cream or The Yardbirds’ right to be classified ‘rock’ would be looked at pretty danged cock-eyed, so that settles it in regard to McPhee and posse, if you ask me. And that’s after we’ve ploughed through the spittle-caked harmonica honk and disgruntled John Lee Hookerisms (the band had backed John Lee on his UK tour in 1964, when they were still in their infancy), and before the forbidding, concrete-boots plod of the closing track, Muddy Waters’ ‘Still A Fool’ lays some proto-Iommi note-bending on you.

It takes, oh, about two minutes of ‘B.D.D.’, the first track on 1969’s Blues Obituary (featuring a sleeve that is not only hall of fame biz, but also a non-sexist precursor to Witchfinder General’s Death Penalty), to confirm that the Groundhogs were keen to kick out their primordial soup music in a thoroughly modern way. Specifically, this means McPhee razing you with solos which inform you why he was sometimes considered a British equivalent of Hendrix. Increased self-confidence and flamboyance is evident over the album’s seven songs: rarely do they lean on blooze chestnuts, Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Natchez Burning’ one exception, and there’s a jazz-like telepathy to the players’ improvisation when they take the pace down on ‘Daze Of The Weak’. Ken Pustelnik, conversely, begins to make with the swinging rolls of a consummate hard rock drummer, especially central to ‘Express Man’ (as is the fact it sounds like the Addams Family theme tune to start with). As for ‘Light Was The Day’, the album’s finishing move, it seems safe to assume that it unglued the conceptions of many horny-handed rockpigs of the era. It sounds nothing like blues, little like rock and if Thurston Moore has intentionally bit McPhee’s tunings on this I would not be shocked.

Although I intend to end this review by telling you to just buy this collection, Thank Christ For The Bomb is the one Groundhogs album you no-foolin’ NEED. It catches them edging further away from the blues, not out of embarrassment but because they keep discovering other things with which they can knock down walls. The sawing boogie-rock riffs which power ‘Strange Town’ and ‘Darkness Is No Friend’, the album’s first two cuts, are utter earworms; there was always something ineffably British about the ‘Hogs, even when they were cranking out trad blues nuggets, but nevertheless this resonantly high-fives Grand Funk across the ocean.

This album is also the first one where McPhee doles out polemic, of the anti-war kind. The title track, a summary of WWII in 24 lines, seems to be riffing on the post-Woody Guthrie protest folk scene; ‘Soldier’, too, profits lyrically from that folkist tactic of singing from the perspective of the bastard enemy. "Soldier, when you see 8,000 climbin’ up on you / Don’t see them as men – just see them as enemies of the king, y’know." For the closing triple whammy we take a fairly logical diversion into class… warfare would be a strong word, but maybe some light sabotage, of the walking-through-Belgravia-slashing-some-tyres kind. ‘Status People’, ‘Rich Man, Poor Man’ and ‘Eccentric Man’ ("If ever I want to I can have the comfort of my country home; but until that time I’m quite content to have walls made of gravestones, a carpet of moss, a ceiling of sky and a brown rat for a watch-dog") are about choosing to live inside of society, or outside… or having no choice in the matter. You wonder if this might have been something that concerned McPhee on a personal level; his band might have not claimed rock star status at the time, but they could touch their hems (via a Stones support slot, for example).

This brings us neatly – and speculatively, I’ll grant you – to Split. The fourth Groundhogs album is probably their heaviest – not necessarily measured by the lowing of their low end, but in terms of the mood and subject matter. McPhee became a troubled figure between the previous album and this one – insular to the point of silence. "My mind and body are two things, not one," from ‘Split: Part Three’ (the first side of the LP was a four-part title track) is perhaps the crucial lyric in what amounts to a damn notepad of couch confessions. The doomy intro to ‘Split: Part Three’ shares consecrated ground with ‘Black Sabbath’, the song, and musically you get the impression the lads might have seen some potential in their high drama; likewise, the disassembled blues of Captain Beefheart. The arrangements get ever more tricksy over these 40 minutes or so, the slide guitar outbursts more wailing – ‘Split: Part Four’ exemplifies this even before the free-rock guitar detonation at the end. (It also has a verse where McPhee attempts to hedge his bets by adhering to Islam and Christianity at the same time.)

‘Cherry Red’, with which Split side two kicks off, is one of those songs that you probably know better than you think you do. It isn’t empirically obvious why it’s become their best known song, but there’s definitely something to be said for getting a bit aled up and nodding, nodding dog-like, to a cyclical bassline which pays no attention to the guitar doing its wrecking ball act over the top. ‘A Year In The Life’ (was everything that sounded a bit like a Beatles songtitle assumed to be a Beatles reference at the time, I wonder to no-one in particular?) is more of that prototypical Sabbathian gloomery; ‘Junkman’ is a genuinely weird shift between pensive jangle and antisocial FX buggery which Julian Cope has accurately described as "like the flushing of an electric toilet". Their old mucker John Lee Hooker is hat-tipped at the end via a wheeze through his ‘Groundhog Blues’, the source of their name. It’s faithful but fugly, sounding uncomfortably close and distorted; if written music was the written word, this would be full of missed apostrophes and unnecessary full stops. A fitting enough ending for an album that consistently prickles you one way or another.

It is 1972, and ‘progressive rock’ is a term being used in earnest by many. Until now, the Groundhogs have issued records which have had a peculiar relationship with this genre, insofar as they have explicitly paraded their love of and debt to early/mid-century black music (prog, in most cases, was about exorcising the blues from rock as much as possible). On the other hand, each ‘Hogs album has showcased an increased virtuosity and weird-ass time signatures and suchlike, and if you snoop around today you can find plenty of people holding up Thank Christ… and Split as sterling examples of the fringe of British prog. The fact that there’s also a strong case made for our boys being punk rock prototypes (a la The Deviants, Third World War or Stackwaddy) is grist to the mill of those who have been tirelessly and for years pointing out that the notion of prog/punk polarity was 98% bogus horseshit. It is 1972, and the fifth Groundhogs album has loads of sweet-as Mellotron bits on it which help to make things even more jumbled than was already the case.

‘Earth Is Not Room Enough’ sounds pretty fancy-free and upbeat, as openers go, until you get to listening for the lyrics. "Cyanide pills dropped in an acid bath / Froth forms a cloud as deadly as death’s own staff / Lungs start to burst trying to hold your breath" – hey, Eighties thrash metal was great, wasn’t it? Overall, the mood isn’t quite as toxically bleak as Split, largely because McPhee has got his sense of humour back. Who Will Save The World? – The Mighty Groundhogs! has a comic book-style sleeve drawn by Neal Adams, a giant of the form who worked for both DC and Marvel, and a song entitled ‘Bog Roll Blues’ in which McPhee considers the rarely-pondered plight of public lavatory paper. He thinks about cottaging quite a bit during this song. That said, the album title alludes to its broad theme, that of a planet heading for man-made destruction due to the greed and myopia of its inhabitants. An instrumental guitar churn through ‘Amazing Grace’ is pitched with the same heavy irony of Hendrix’s ‘Star-Spangled Banner’.

Musically speaking, much light shines through the despair thanks to the keyboard parts and McPhee’s electric-folksy fingerpicking, used winningly on ‘Wages Of Peace’ and ‘Death Of The Sun’, whose guitar breaks remind me of the earlier REM albums. Then there’s ‘The Grey Maze’, which ends the album and lasts over ten minutes. It is upbeat, starting off at a boogie-ish tempo, but the guitar yowl and cro-magnon drumming quickly start to sound so fried – if only through repetition – that a sort of darkness falls. Actually, I’ll tell you exactly what this pretty much blueprinted: ‘Reoccurring Dreams’, the frighteningly OTT 14-minute instrumental on Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade. ‘The Grey Maze’ isn’t quite as fucked as that, but it’s close; you suspect that the Groundhogs had wanted to put something like this on wax for a while.

There is a large back catalogue after these five albums: some credited to Groundhogs, some to Tony McPhee or some variation thereof. (The sixth, 1976’s Solid, is accurately named.) However, it’s not just the convenience of the band leaving the Liberty label after Who Will Save… that make this a choice encapsulation. It was the last album featuring Ken Pustelnik’s drumming, a lineup switchup which began a procession of dozens of member alterations; from here on in, it’s McPhee’s gig even more than it was before, unless you’re talking about Pustelnik and bassist Pete Cruikshank’s time as The Groundhogs Rhythm Section, with various folks filling in for McPhee. They might have needed it for bill-paying purposes, but no-one else does. This here is what they need.