"…We’ve been rockin’ an’ rolling in your arms / rockin’ an rolling in your arms…" It’s a sentiment we’re all familiar with. A line we must’ve heard more than a dozen times. Here sung in four part harmony with no discernible back-up instrumentation. But there’s something not quite right about the melody. It’s closer to the rootsy American folk of Pete Seegar than the good rockin’ of Elvis, Chuck, or Jerry Lee. And the verses are enunciated by turns in the declarative style of a Southern preacher. What was that last line of the chorus again? "Rockin’ an’ rolling in your arms / In the arms of Moses" closing on a great ‘Amen’ of a plagal cadence.

This track isn’t a recording of some 1980s trendy vicar or televangelist, nor is it a rare cut from the mid-50s, one of the King’s more devout contemporaries. The record we’re describing is from 1916. It’s called ‘The Camp Meeting Jubilee’ and it’s by an unknown male vocal "quartette". Unknown because Little Wonder, the label which originally released it, was not in the habit of identifying the performers on their records. This one comes in at just shy of two minutes because that was about all you could fit on the five and a half inch shellac discs they sold through the Sears and Roebuck catalogue at ten cents a pop.

Little Wonder Records had a studio on one of the floors of the Woolworth Building, that 792 foot cathedral of commerce that was then the tallest building in the world. It was most likely in that studio that the anonymous singers of ‘The Camp Meeting Jubilee’ laid down the first known recording to employ the phrase ‘rock and roll’, just a few floors down from the studios owned by Little Wonder’s parent company, the Columbia Phonograph Company. Few people at the time knew that Little Wonder was owned by Columbia – that arrangement was kept secret by contract, so perhaps Little Wonder was the first boutique indie label.

If it comes as some surprise that this first mention of rocking and rolling had very little to do with teenage sex (indeed, the teenager would not even be invented for another quarter of a century), then be reassured by what may be the phrase’s second recorded iteration. The sly innuendo and boozy slur of Trixie Smith’s ‘My Man Rocks Me (With One Steady Roll)’ should leave its audience in little doubt exactly what is referred to by the "tricks" which give the singer "a smile . . . night and day".

More than just a slip in moral fibre had changed between the 1916 of the first and the 1922 of the second of these two contenders for the self-consciously impossible title of ‘the first rock and roll record’. Technological and economic changes which would provide the conditions of possibility for the emergence of rock and roll as a genre and, ultimately, hegemonic force in popular music; thus creating the possibility of retrospectively seeing Trixie Smith and the four singers employed by Little Wonder as unconscious precursors.

Firstly, and perhaps foremostly, radio. The first regular broadcast from a commercial station in America had begun in 1920 in Detroit. By the end of 1922, radio stations had spread from Texas to Maine, and from Florida to Oregon.

Secondly, the music business had witnessed a power shift from songs to records. In 1916, advertisements in the entertainment section of the newspaper were still dominated by publishers pushing their latest songs, pointing out as a matter of fact that such and such a popular ditty was available on a number of different labels and by a number of different artists. By 1922, everything had changed, and the same ads were being placed by record companies, trumpeting the greatness of their performers. An ad placed by the Black Swan label in the 16th of December issue of the Chicago Defender, for instance, proudly declared that Trixie Smith had recently received the silver cup in a blues singing contest at the Inter-Manhattan Casino in New York, "presented by Mrs. Vernon Castle."

Black Swan, who had released ‘My Man Rocks Me’ earlier in the year, was perhaps the first widely distributed label that could claim to be "of, by and for colored people" as put by another ad, placed in that same year, in The Crisis, the W.E.B du Bois edited journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

By the end of 1923, both Black Swan and Little Wonder will have been declared bankrupt, but "rock and roll", the fertile ideational pollen they had helped release into the world, was just making its first flutters upon the breeze, seeking fresh flora to inseminate.

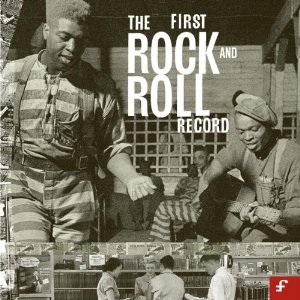

There are essentially two methods being put to use by this delightfully packaged first release from the Famous Flames Recording Company. The first is etymological, tracing, as we have seen, the earliest uses and conjunctions of the words "rock" and "roll" as well as associated terms, such as "mess around" and "shake that thing". The second is more genealogical, seeking out family resemblances in "RnB combos, black vocal groups, honking saxophonists, blues belters and several white artists, playing in the authentic RnB style". In these respects, the compilers follow rock and roll’s own contemporary self-understanding, following DJ Alan Freed, who both popularised the term and adumbrated the foregoing criteria.

In his (1996) book on the Aesthetics of Rock, Theodore Gracyk argued that the term rock and roll was gradually adopted over the course of the 1950s as replacement for "rhythm and blues" in order to indicate that the music was performed by black and white alike. When Elvis Presley (represented here by two of the last tracks on the compilation) was first interviewed on a Memphis radio station, the DJ made sure to ask Elvis which school he had attended in order to make clear to the local audience what colour his skin was.

Freed’s sleight of hand is brought into sharper relief on the evidence of those tracks here included by dint of semantics: evangelical gospel singer, Sister Rosetta Tharpe; the sweet close harmonies of the Boswell Sisters (referring to the "rolling and rocking rhythm of the sea"); a Judy Garland number from George Sidney’s MGM musical, Thousands Cheer. Rock & roll sounded safe.

In fact the history of black and white musical cross-pollination is as old as American music. Earlier in the century, Sidney Bechet had blamed white northerners for the change in nomenclature from "ragtime" to "jazz", and Elijah Wald has suggested that already jazz, like rock & roll, was "a new name that signified white dancers catching up with black styles rather than a new music."

The crystallisation of the sound we now recognise as rock & roll can be traced back to the struggles over royalties in the late 30s and early 40s. Two successive quarrels, first between the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) and the radio networks, followed by the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) recording strike of 1942-4, would ultimately lead to the system of royalties from radio play and recordings for composers and performers that sustained the livelihoods of most musicians and composers throughout the rock era.

They would also result in a great deal more airtime for so-called "race" and "hillbilly" records whose authors were represented by neither ASCAP nor the AFM. For that sector of the radio audience too young to go to war, these records seemed to offer a fresh, raw sense of real, lived experience that was miles away from the culinary pop of the time. When they grew up, they made, and listen to, rock & roll. Listening to rock & roll, then, is to cross a kind of sonic picket line.

But, my word, there are some delightful cuts spread across these three discs. The gruff exultation of Clarence ‘Pinetop’ Smith on ‘Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie’ ("That’s what I’m talkin’ bout!"); the thunderous rhythms of Gene Krupa backing up Benny Goodman on ‘Sing! Sing! Sing! (With a Swing)’ (last heard at the beginning of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive); the squealing freeform sax of Illinois Jacquet’s ‘Blues Pt.2’; the sass and schtick of Ella Mae Morse and Freddie Slack ("Well, Baby, you’re play gives my wig a solid flip / You snap the whip, I’ll make the trip") on the ‘House of Blue Lights’; the earthquaking explosions of tremolo guitar on Hardrock Gunter’s ‘Gonna Dance All Night’; the deep velvet tones of Bill Brown’s lead vocals on The Dominoes’ ’60 Minute Man’ like a big, rich full-butter cake of sex.

Thanks to a delightful small print sleeve-note informing the listener that "we abhor the overuse of such [noise reduction] techniques by some other labels with appalling results" there is also a delightful layer of crackle and hiss, providing such tracks as ‘The Camp Meeting Jubilee’ with almost Philip Jeck levels of fizzing, coddling surface noise. Sufficient to delight fans of Ghost Box’s spectral electronics easily as much as those in search for the authentic roots of the rock myth. This record is not interested in exploding mythologies or demystifying legends, but nor does it seek to conceal their status as myth.