Back in autumn 1977, I sat and watched Kay Carroll, Fall manager and girlfriend of Mark E Smith, as she Biro-ed the finishing touches to the sleeve of the band’s sprightly second single, ‘It’s The New Thing’. As I watched Kay’s indelicate evocative artwork, sitting in the chaotic interior of the couple’s Prestwich Flat (Rectory Road, if you must know), I imagined The Fall ploughing through the years in a lo-fi heaven. And now I sit here running my fingers across the lovely high-end gloss of this Beggars reissue.

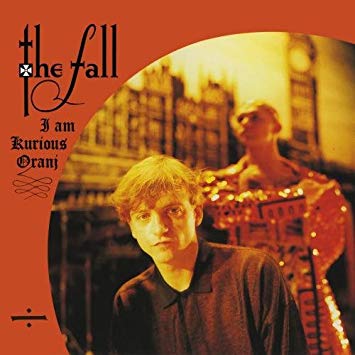

It is a beautiful product. Always the loveliest of sleeves, with the orange arch framing Mark in his curiously beautiful pomp. You open the gatefold to discover a stunning collection of photographs, by Richard Haughton and Kevin Cummins, which perfectly capture The Fall’s unlikely foray into Sadler’s Wells Theatre, thrillingly accompanied by absurdist dance troupe Michael Clark & Company. Just to further push this fact, the programme of the 18-day run is slipped into the gatefold. A lovely touch. In the climate of 2018, this reissue might be worth the purchase price before you even play it.

For die-hard Fall fans, this period – 1988 – proved both thrilling and unsettling. What the hell was going on? As we filed into The Royal Northern College of Music to see The Fall, Michael Clark and Slovenian art punks Laibach, we seemed an awful long way from The Squat Club in 1977. Fellow gig attendees now tended to be bearded Guardian readers loudly pondering the impact of what author Dave Thompson called “cross-cultural terrorism”. I guess that remains the best way to view this.

The ballet/play(?) itself – rather like the preceding and similarly detached Hey! Luciani, made little sense and will not be challenging Harold Pinter. It was casually based on the Dutch Prince William of Orange and his fervent Protestant hope to conclude the ‘curious’ period by usurping Papist James II as British monarch in 1687. But don’t look too far into this; the scenario was used as little more than a backdrop to Clark & Co’s exotic and bottomless dancing and a new batch of Fall songs which fully included the still-evolving musical and visual presence of Brix Smith.

That is the balance maintained here. The dark heavy undertone of an ongoing protestant/Catholic battle is somewhat belied by a stage set that sees Brix wheeled in on a giant hamburger and a carton of french fries which spills over, killing the dancers dead.

Fall fans complained about the pretentious nature of Clark & Co while the dance fans complained, perhaps not unreasonably, that The Fall’s music was basically un-danceable and fronted by a man incapable of singing or taking his hand out of this trouser pocket.

Well, once the paraphernalia has tumbled out of the gatefold, we are left with a Fall album that is eternally divisive. A typically Fall-esque patchwork emerges and, as ever, the ironies stack up. Arguably, this is the album where Brix Smith’s musicality – and sheer glamour – begin to shine. The lovely fat guitar of ‘Overture from I Am Kurious Oranj’ is a mighty Fall-esque tower of strength; same goes for the primitive echo of ‘Big New Prinz’ and the hilarious ‘Wrong Place, Right Time’, an infectious chant which got firmly lodged into mid-period Fall’s live sets.

The greatest irony is that I Am Kurious Oranj, from ballet to album, also showcases the breakdown of the marriage between Brix and the band’s truculent leader, as she worked on her side-project/escape route – The Adult Net – and he apparently wrote lyrics that were personal attacks draped in ambiguity. (A trick that Morrissey also conquered around the same time.) Nothing is frustrating in quite the same way as the knowledge that a song is about you, although no one else would ever know it. Such is the case with ‘Bad News Girl’ and Brix who, to this day, is not 100 per cent sure it’s about her. (It is, though. Of course it is.)

And so, we have drifted far from the album’s original concept, and there is a messy element here that appears to fight against Ian Broudie’s slick production. Perhaps that was another internal struggle used to add essential angst; there is certainly the sense that Mark wrote most of this on the back of beermats in The Forester’s Arms.

There is a Mark E Smith mural now, clasped to the side of his favourite Prestwich chippy. This new landmark – a mystery to most locals – probably wouldn’t exist had the Fall never produced moments such as this, where absurdity and day-to-day minutiae clash to such vivid effect. A true hinge moment of the late 80s, and 30 years later there is still no other band quite like The Fall.