The Dwarfs of East Agouza is a trio that bridges myth and daily life. Through improvisation and genre-blending, they challenge expectations for music tied to a specific place. The group features Maurice Louca (known for Lehkfa, Karkhana, and his solo-ensemble projects), Alan Bishop (of Sun City Girls and Sublime Frequencies), and Sam Shalabi (of Land of Kush and Karkhana).

The band’s name evokes a fairy tale, so listeners may expect fantasy instead of music grounded in post-improvisation, contemporary folk and electronica. However, the name refers to the Agouza neighbourhood in central Cairo. The musicians were neighbours there and began playing together with no set outcome in mind. This irony is central: their music cannot be reduced to a single genre, nor should it be. The intention (or rather, no intention at all) is to cross musical boundaries.

Shalabi, who also plays the oud (but not on this record) and brings a unique approach to guitar, was influenced by punk rock as a teenager. He admired The B-52’s Ricky Wilson, who used a guitar with two strings removed. For months, Shalabi played a similar four-string guitar. Later, he discovered the oud, which requires more skill because it lacks frets. This experience transformed his fingerpicking. It enabled him to play guitar with both rawness and subtlety, combining oud techniques with punk energy in The Dwarfs of East Agouza.

Maurice Louca’s rhythms are made with drum machines, but they sound natural, not synthetic. Sometimes, it feels as if a percussionist is playing live, even though all the beats are programmed. The sound shifts between organic and machine-like at different times. The band’s name connects them to a location, but musically, the group is three distinct individuals. Alan Bishop might seem less visible than his bandmates, but his contributions stand out. He switches between guitar, quiet saxophone lines, and atmospheric vocals. Sometimes these vocals are haunting and feel supernatural.

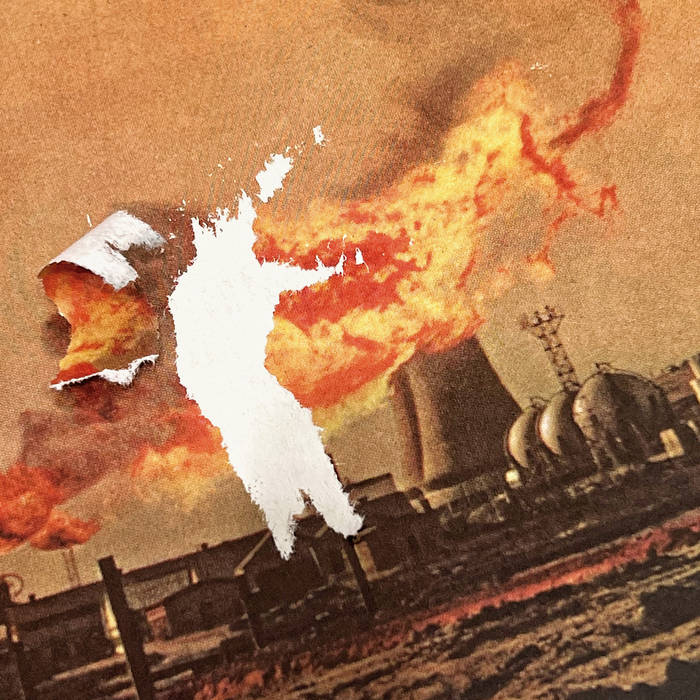

Sasquatch Landslide, their eighth album, further refines this approach. Here, the songs are shorter and more tightly focused than on earlier records like Bees, Rats Don’t Eat Synthesizers, or The Green Dogs of Dashour. Yet time inside these tracks remains flexible: concise without feeling compressed, letting heavier moments unfold gradually. The winding guitar lines deepen the dreamlike mood. With Sasquatch Landslide, the band condenses improvisation into a compact space, keeping their energy open and inventive. This album reinforces their reputation for innovation and experimentation.

This music is rhythmic and trance-like, but it avoids simple patterns, favouring loops, unexpected changes and surprises. ‘A Body to Match’ feels like a surreal painting in which you try to focus on the new elements, but the edges fade into a kind of quasi-desert blues.

‘Double Mothers’ flows next, evoking turntable effects – slow spins, loops, irregular beats, and a broken tape quality – layered with saxophone and fragmented guitars. Though not deconstructed, the music can feel that way during improvisation. ‘Goldfish Molasses’ follows, defined by unusual rhythms, sharp guitar, and Bishop’s whispering voice, as the track dissolves into a chanting, meditative mood. ‘Neptune Anteater’ highlights percussion, soon joined by a rough guitar for contrast. ‘Swollen Thankless’ builds from a subtle melody into an immersive trance, while psychedelic guitars, keyboards, and electronic percussion create music that feels ever expansive. Finally, ‘Saber Tooth Milipede’ unfolds from a basic rhythm, letting guitars shape a tense, hypnotic space.

The Dwarfs of East Agouza craft music freed from specific places. Their ironic titles and playful band name contrast with their serious focus on sound. They offer listeners a psychedelic experience that defies simple labeling. You can hear them improvising and being open to whatever happens. Their collective playing has a fresh aspect – inviting you to lose yourself in a trance, hypnotic textures, and a range of unusual sounds. The music started with a chance meeting in Cairo, but it now feels like it maps a place that does not exist. It seems to lead you nowhere – and that is the point.