"I knew I would leave you with babies and everything…" – ‘Disintegration’.

It was the end of the 80s, and the end of our youth. We had been goths, if you like; certainly, we had grown up listening to The Cure, and bands like them, bands that wore black and sang songs about existential dread that you could dance to, swoon to, drink to, fuck to. Bands that knew about glamour, knew that dressing up and painting your face, primping your hair and striking a pose, were as valid a reaction to the futility of everything as close-cropped, serious sobriety or a drunken nervous breakdown.

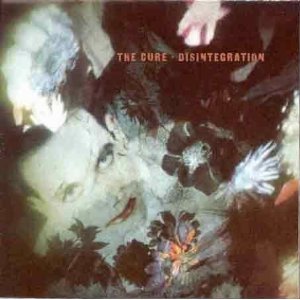

It was the end of the 80s, the end of our youth. For some of us there would be new friends in a new town, and new bands to be listened to as we realised that describing yourself as a Cure fan marked you out as the most narrowly and naively provincial of first year students; for others there were shit jobs and dole queues. Actually, there were shit jobs and dole queues for all of us, eventually. But first, there was one last album; one last great record of the gothic age. After the sprawling, multi-faceted Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, Disintegration was the kiss-off; the last swim in those deep dark waters before we too fragmented, took on responsibilities and families, or didn’t, and lost ourselves in the swirling undercurrents as drugs and drink and mental illness ceased to be our playthings and took control instead. Whatever, after 1989, The Cure weren’t the same, and neither were we. Neither were any of their peers, for that matter; The Banshees, The Sisters, The Cult, The Mission… all broke up or suddenly seemed incapable of making a decent record once the decade that defined them was over.

Some people say that the Cure aren’t a goth band. They’re wrong. Robert Smith’s drum machine-driven, instrumental demo of ‘Prayers for Rain’, which opens disc two here, could almost be a retroactive blueprint for the whole genre; certainly, you could lay a Siouxsie Sioux or an Andrew Eldritch vocal over the top without either artist leaving their comfort zone. I see no shame in this, as you may have gathered; but it’s The Cure’s undeniable gothiness, their melodrama and purple passages, all that hair and lipstick, that means they can never quite be taken seriously. As good as they are, there’s still a whiff of patchouli about Seventeen Seconds and Faith that stops them being in quite the same league as, say, Unknown Pleasures or Metal Box.

There’s something a little bit gauche and adolescent about The Cure. They’ve written some brilliant songs that mean a great deal to a large number of people, but at the same time they’re seen as a band that you grow out of. And by and large, this is all true; Disintegration however, is the exception. I don’t know if it’s their best album, but it’s certainly their most mature: the last of the 80s, and the last of their classic period. Reflecting on the life journeys of the past decade, it doesn’t deny the follies and passions of youth, but absorbs them, dignifies them, sums them up and lays them aside, without too much regret. Disintegration is essence of Cure, perfected, refined; after this, there was nowhere else for them to go. They were never this good, never mattered this much, ever again. But Disintegration remains the Cure album you can still listen to, twenty-one years on; without embarrassment, and with a great deal of bittersweet pleasure.

"Whenever I’m alone with you / you make me feel like I am home again" – ‘Lovesong’.

And now it’s back, reissued in this deluxe, re-mastered three-CD format. Disc two, misleadingly titled ‘Rarities,’ is largely a load of ropey old rehearsal tapes, and is utterly inessential; disc three is a remixed and expanded version of the previously available Entreat live album, and consists of the whole of Disintegration played, in order and pretty much note-for-note, at Wembley Arena in 1989. Fine as far as it goes. But it’s disc one, the original album, that we’re really here for. Scrubbed up nicely, Disintegration still sounds simple and perfect, conjuring up emotional depths and rich autumnal colours with a few deft brushstrokes. Every instrument does no more than is strictly necessary; the bass and drums setting up a steady, unhurried groove for a three-note keyboard melody, the guitar wandering unobtrusively between, setting up resonances, counter-rhythms and counter-melodies, but never crowding, merely suggesting the possibilities inherent in so much space. Smith’s vocals seem to settle on one of a near-infinite number of possible tunes, stepping lightly through the structure, dodging the beat, yet making each room they pass through their own.

Disintegration has been described as a sequel to 1982’s wrist-slitting fan favourite, Pornography. Yet the two albums are very different. Pornography is dense, claustrophobic and virtually tuneless- in the best possible sense. Turgid and deliberately ugly, drowning in self-pity and occasionally lashing out with bursts of savage loathing, Pornography sounds like depression feels: sucking all positive energy into a black hole of utter negativity. But Disintegration is spacious and melodic, and filled with moments of great beauty. Its pace is stately and elegiac. Bells twinkle like stars in the midnight sky; melodic basslines weave their way through the gentle sadness of sighing guitars and keyboards that rise up like glaciers. Certainly, to the unaccustomed ear, there is doom and gloom aplenty; the abyss is never far away. But this is the Cure we’re talking about, after all. These things are relative. Disintegration is a melancholy record, but not a depressed one.

"Sometimes you make me feel like I’m living at the edge of the world. It’s just the way I smile, you said." –Plainsong.

‘Pictures of You’ deals with heartbreak and regret, but it’s wistful; there is still love and admiration for the one that got away, the lover that the narrator could never be equal to. ‘Lovesong’ is just that- no edge, no irony, just Smith’s wedding present to his long-term partner Mary. The spindly funk of ‘Lullaby’, tripping on the offbeat, anticipated the dark, English hip-hop of Tricky long before it was sampled by the likes of Just Jack and Rachel Stevens. It’s ‘Love Cats’ turned inside out, creepy-kooky, bad dreams on Top of the Pops and that video scarring a generation of kids on Saturday morning’s The Chart Show. And then ‘Fascination Street,’ the American hit, the epic intro with that churning bassline moving through a dark desert landscape lit with neon flashes of keyboards and guitar, images strobing into view as the drugs take hold, finally pulling into the city limits- "oh it’s opening time down on Fascination Street…" And one last dance, one last drink, one last messy fuck before we say goodbye forever… chiming shining arpeggios flash like knives in alleyways.

On the original vinyl, side one had the hits, but side two hid the darkness. Side one was for dancing in the clubs, partying on snakebite and cider with your painted friends, but side two is what happened back at yours, though both of us can barely remember, or barely want to. "A hold on me so dull it kills, you stifle me, infectious sense of hopelessness," spits Smith on ‘Prayers for Rain,’ as layers of treated keyboards drone sickeningly, and guitars circle like bad habits, repeating the same pattern over and over. A narrative about being buried alive in a destructive relationship, stagnating, trapped, and having to cut yourself free from the other, the one you wanted to help but who only ended up dragging you into their own cycles of misery. It’s hard not to see this song as Smith’s shout of frustration with his once-close friend, the soon-to-be-sacked Lol Tolhurst; by this stage a hopeless lush whose only contribution to the band he helped form was to be the designated scapegoat and butt of cruel jokes- a more valuable role, it turned out, than anyone realised, as after he left the band tore itself apart on the subsequent Prayer world tour. Smith was praying for something to break, and eventually it did.

Tolhurst’s sole musical contribution comes in the form of one-note keyboard stabs on ‘The Same Deep Water As You,’ another song about mirrors and drowning, about losing it, allowing the sirens to call you to slowly slide under and slip away. The title track is another song about endings and break-ups, its fast, unrelenting beat letting the bitterness of the lyrics pass without comment, keeping you from breaking down, keeping everything sharply spiteful and sardonic. A sound like breaking glass recurs in the background, and the backing vocals are queasily high-pitched, like the aural equivalent of funhouse mirrors. And finally the bittersweet, reflective ‘Untitled,’ the perfect ending; music for walking away. "Never quite said what I wanted to say… and now the time has gone."

It was all over- the 1980s, our youth, the context for records like this, and indeed The Cure as a vital, creative force. In interviews at the time, Smith said that this would be the band’s last album; that he thought of it as such while he was writing it. He was turning thirty, and believed that it was impossible to make a great rock record after that age, so this was his last chance. He was right. The Cure would return, of course; becoming the stadium band Smith always feared they would, with creaking, gargantuan world tours, and a new album with a new line-up once every four years. But they were irrelevant dinosaurs from 1992 onwards. The world had changed; we all had to grow up, move on, and mostly, we left The Cure behind. But we found, to our surprise, that we could take Disintegration with us.