With the benefit of hindsight, it’s with a sense of amusement that one considers the howls of derisory laughter that met the release of The Cult’s second album, Love, in 1985. In the eyes of a music press that had regarded heavy metal as the idiot half-brother of all that was supposedly hip and tasteful, The Cult had made the verboten move of stepping backwards into the world of classic rock in order to move forward.

But it wasn’t just the music press that recoiled in revulsion at The Cult’s calculated repositioning. In much the same way that New Order lost the support of a sizeable number of the overcoat brigade in the wake of the sleek electronic beats of ‘Blue Monday’, so The Cult were rejected by those who’d backed singer Ian Astbury from the off in his darker previous incarnation fronting Southern Death Cult. Yet, looking back after a gap of 24 years, Love is more of a transitory album than the quantum leap it was perceived as at the time.

While not quite swan-diving into the decadent swamp of unfettered plank-spanking pleasures, The Cult nonetheless looked to the then-unfashionable spectre of Led Zeppelin and any number of British blues-based rock bands from the (to early-80s eyes) terminally unhip period of the late 1960s. Not that The Cult gave a shit. Like The Sisters of Mercy before them, they knew the value of hanging a guitar suggestively around the hips rather than using it to keep the nipples warm. Rock was something to be celebrated, a form of communion that arrived with all the force of a liberating army for those who’d been forced to hide their Led Zep albums down the back of the sofa since the last days of the punk wars.

The funny thing about hearing the first chimed shards of ‘Big Neon Glitter’ tumble from the speakers almost a quarter of a century after they first offended post-punk sensibilities is that they sound more akin to the delayed pluckings of U2’s The Edge than the riffing of Jimmy Page. Indeed, The Cult themselves had attempted to secure the services of the Dubliners’ erstwhile producer Steve Lillywhite, but instead found themselves under the auspices of one-time Wham! knob-twiddler Steve Brown. It proved to an astute pairing. Brown gave The Cult a muscularity that had been missing from their previous long-player, Dreamtime, and in doing so plotted a new course for a band hungry for success on a worldwide scale. Within seconds of the needle hitting the groove, The Cult had drawn a deep line in the sand. Inevitably, they ostracised a large part of their constituency by marking themselves out as patchouli-stinking hippies embracing the glorious pomp of something called ‘Nirvana’. This was nothing short of sacrilege in the battlefields of Thatcher’s Britain, to a generation raised to believe that hippydom was little more than pot-smoking, flares and lentils thanks to Nigel Planer’s portrayal of Neil in the seminal comedy The Young Ones.

But there was more to The Cult than dreams of hitting the hippy trail and speaking to elders from a distant race. In Ian Astbury they possessed a frontman who revelled in the ludicrous nature of rock, providing a preening, cock-thrusting alternative to the pretty boy ponces who’d happily to bought into the materialistic bullshit of the day. At his side was Billy Duffy, a guitarist who knew the value of drones and eastern scales as well as the killer riff; he had enough hooks to reel in the ears of those hungry for something with power but unwilling to compromise with the spandex brigade. That’s why ‘She Sells Sanctuary’ proved to be such a floor-filler then and remains so to this day. Only a churl would complain that ‘Rain’ was the same song but played slower; The Cult had a hit a groove and they were going to go deeper. The passage of time also reveals the wah-wahed, plank spanking ‘Phoenix’ to be a slinky little mover of the finest calibre.

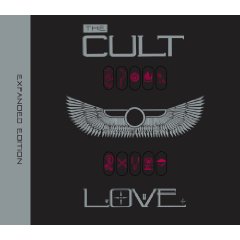

This omnibus edition tells the tale of Love in great detail — it’s a lavish and lovingly packaged box-set including extra discs of 12” singles, B-sides and pre-production demos — and may prove to be something of a shaggy dog story for some. But the remastering of the original album gives the songs a hefty dose of bollocks, showing where The Cult where headed to next. Indeed, the fourth disc, a live recording of The Cult from the Hammersmith Odeon in late 1985, finds the band already chomping at the bit in their desire to increase their — ahem — heaviosity. It wasn’t long before The Cult abandoned work on Love‘s follow-up with Steve Brown and teamed up for the truly magical pairing with Rick Rubin on Electric . . . but that’s another story for another day.