Rock & roll is where you find it. Likewise, the exotic. Which may explain why The Clientele, a band as unmistakably of the southern part of England as any, ever, have fared better in America than in their own country. They are one of those acts whose music captures so completely a sense of time and place, it might almost have been painted rather than played. The time is autumn and the place the leafy suburbs of the home counties. The Clientele infuse what is, to most who live here, ordinary terrain with the kind of mystique we would more traditionally attach to, say, the landscapes of Americana or Springsteen’s New Jersey.

To me, however, southern England isn’t ordinary terrain. I’m not from here, and even though I’ve long called it home, it has never ceased to feel peculiar to me. Perhaps The Clientele’s American audience feels the same. Perhaps they hear the exotic in this music just as I do. But then, The Clientele themselves are from here, and they, too, evidently find it a numinous and uncanny place. Uncanny in Freud’s sense, of being at once familiar and eerie. “Stranger than known,” as the Byrds described the England by which they were inspired at a distance and bewildered up close.

I’ve avoided learning more about The Clientele than I need to – I don’t even know what they look like – because I find their records so evocative I don’t want faces, biographies, personalities coming between me and that feeling. But I do know they emerged from Hampshire and that their founding duo bonded at school over a love of Felt; and that they sound exactly the way a band of whom this is true ought to. Their last album, Bonfires On The Heath, is eight years old now. It is a beautiful thing, pliant and warm and faintly sinister all at once, with something atavistic, something pagan, stirring in its moonlit branches, creaking gently in the wind, and moving, slow and whispered, over the darkened pathways below. I was almost afraid to listen to their comeback, Music For The Age Of Miracles, not because I feared it would spook me but because I worried it wouldn’t. I needn’t have. It’s every bit as magical as its forerunner.

When I first heard The Clientele, their shimmering harmonic languor put me in mind of Pink Floyd; specifically, the pastoral-psych Pink Floyd whose Cambridgeshire summers were as exactly realised as are The Clientele’s Hampshire autumns. They still do, but there is a vital difference. Floyd’s sunlit Grantchester Meadows, their church bells heard along the Long Road and on down the Causeway, are profoundly nostalgic, a wistful mainline to childhood. The Clientele’s vividness lies in the present, or in a present; and far from finding innocence and safety therein, the songs of Alasdair MacLean – lovely, elegant and mysterious songs – always convey a subtle menace. Its fur brushes past you in the dark, softly enough, but there are teeth there somewhere and you tense and hold your breath.

Snippets of the lyrics reach out and coil themselves around my memory after each song is over. Such as the first words heard on the album, on ‘The Neighbour’, which glides along swan-like on strings – guitar, plucked and violin, bowed: “Evening’s hymn / Conjures the park / And now, out of the dark / In a dream I followed you home.”

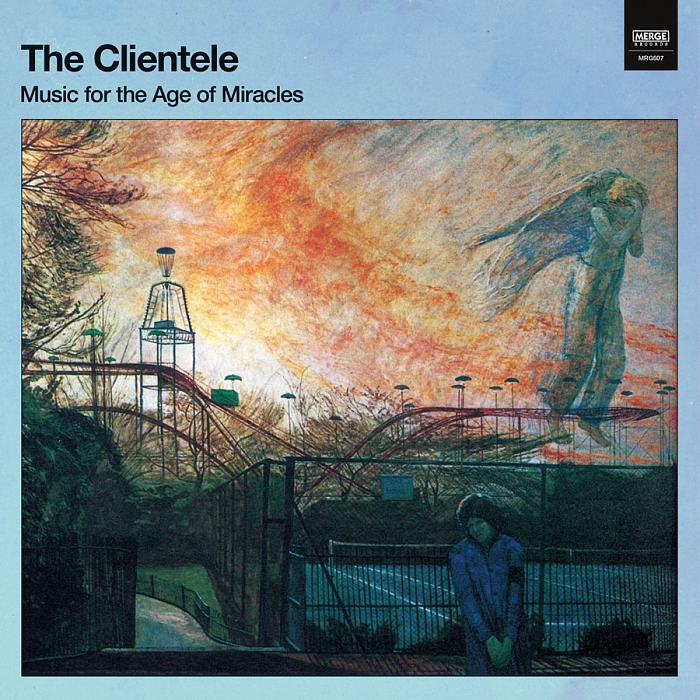

Just as the hour is always dusk, so the atmosphere is one of hypnagogia, that state when wakefulness drifts into sleep and dreams are as real as the world they replace. The Clientele grasp this is how these places are. I don’t know how many times I’ve walked through such parks, past tennis courts just like those on the album cover, along lamplit streets, and felt that same slight thickening in the air, that same frisson of not quite knowing. I never realised there was music precisely for that feeling until I heard this band.

This, then, from the delicate, rolling ‘Lunar Days’: “So, I walked along the street with no one home / Lamps no one lit, roads no one drove… / This is the year that the monster will come.”

A premonition echoed in ‘The Neighbour’, which warns – or celebrates – that “the old Gods are returning.” What The Clientele recognise (or perhaps what I read into this record, in today’s ugly and hopeless political climate) is that here in cosy England, there is serenity and there is enchantment, but there are also malevolent spirits stirring, which if given their freedom will swarm across the land. Powell and Pressburger, perhaps England’s greatest film-makers, were English in just the way The Clientele are English (and MacLean was born Scottish, just as Pressburger was Hungarian), and they understood this; their 1944 film A Canterbury Tale has just that air to it.

Not everything here is so fraught with omens, but most of it is fraught with something. Not that you would know if you put it on to play and let it float over you, which it will when you don’t pay attention. It has that ease to it, augmented by new member Anthony Harmer, an old pal of MacLean’s whose santoor (an Iranian dulcimer) and string/brass arrangements add a further layer of resonance to the group’s haunted sound. But keep even half an ear open, and you will be repaid many times over; something will catch it in passing, some phrase or image perfectly redolent of a moment, a feeling you have known yourself.

Three ambient instrumentals by drummer and pianist Mark Keen aside, the one track that breaks the pattern is ‘The Museum of Fog’, which falls into that curious subgenre of spoken-word indie to which Pulp and Tindersticks have made definitive contributions. Its narrative is as direct as those on the other songs are oblique, and its tale of being strongly affected by chance attendance at a pub gig somehow fits just-so with the mood of the album. The narrator experiences there what the listener, or at least this listener, experiences here: a connection to something within himself from the music, one not fully explicable.

Those American fans, most of whom have surely never set foot in the places The Clientele invoke, are onto something here. This album, more than any punk tune, is the sound of the suburbs; rather than being from the suburbs, it sounds like the suburbs. If you think that’s no recommendation, just hear it. There is beauty here, and sadness, and peril, and deep, deep soul.