There’s a common analogy that paints dub artist as alchemist or laboratory technician, spending anxious hours hunched over esoteric pieces of equipment in an effort to crack the magic formula that turns base sound into reverb-drenched gold. It’s there even in their names: King Tubby’s protege Scientist, for example, or London’s prolific Mad Professor. He might lack the accompanying moniker, but throughout his tenure in Techno Animal, The Bug and King Midas Sound, Kevin Martin’s weird science has opened up a sonic space just as bass-heavy and idiosyncratic as dub’s most revered names.

Martin’s great skill is in making ostensibly well-known motifs feel thrillingly unfamiliar. From the perspective of a Londoner, the city streets he portrayed on London Zoo and King Midas Sound’s Waiting For You were packed with instantly recognisable references to place, community and atmosphere. However, in his hands they were chemically enhanced, sometimes to near-grotesque extents, to highlight aspects that might previously have gone undetected: the bleak humour in chilling murder ballad ‘Skeng’, or Waiting For You‘s freakily lonely portrait of headphone-clad urban alienation. He’s also become increasingly enamoured with the classic dub trope of the version, inviting different vocalists to voice a single riddim and in doing so drastically transform its contours and overall mood. In King Midas’s Kiki Hitomi’s hands, for example, the ‘Skeng’ riddim was stripped of its bulging aggression and left serotonin-depleted, its vague sense of menace delivered via jackhammer pressure that pounded on the temples like a pneumatic drill.

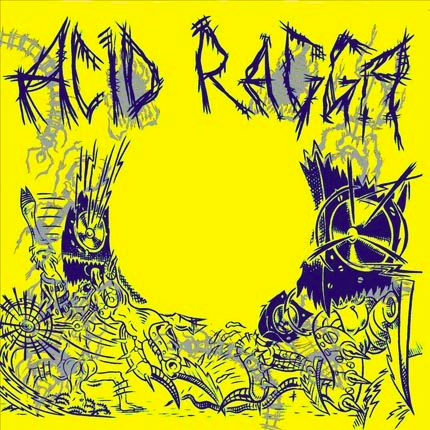

His latest project – the first ‘proper’ new Bug material since 2008’s London Zoo – is another scientific endeavour: an exercise in genetic recombination, triggered by a long-unanswered question that’s apparently been burning in Martin’s mind for years: "What happens if I cross acid house with ragga?" Leading up to the release of his long-awaited new Bug album proper Angels & Devils, his Acid Ragga 7" series attempts to answer that question via a series of gene splices that transfer traits from each test subject into a new and virulent third form, a sort of Frankenstein’s monster of the electronic dub world that roars along at breakneck speed. Its artwork, by Zeke Clough (generally known for his distinctive designs for Skull Disco and Shackleton sleeves), portrays these experiments as giving rise to a cybernetic nightmare zone, where bodies jack directly into the mains, hunks of flesh and splattered blood interface with archaic weaponry, and the MC’s brain receives instructions via flexible tubes plugged into his skull.

Still, on ‘Can’t Take This No More’ Daddy Freddy does a good job of ignoring – in fact, actively resisting – the influence of those infernal forces. A scathing commentary on a world sinking deeper into economic turmoil, he delivers its chorus in a throat-shredding roar – "Me can’t take this no more / Rich a’ get a’ richer and poor a’ get poor" – above a bounding dancehall rhythm. Disembodied voices form a dissonant serenade somewhere in the middle distance, pinned in place between zig-zagging bass scrawls and occasional snare drum cracks.

The same track backs B-side ‘Rise Up’, again furthering Martin’s love for re-versioning existing music. His treatment of Inga Copeland’s vocals is similar to her music with Hype Williams – they’re turned into half-obscured thoughts, smeared with enough reverb and delay to cloak their lyrical content. She’s a far more ambiguous presence than Hitomi, to whom her vocals bear a superficial resemblance. Though Copeland’s delivery might be blunted it’s far from placid or saccharine, and the track’s sense of overwhelming dread is heightened by the sense that beneath her calm exterior she’s seething with passive aggression.

In tone and subject matter, Daddy Freddy’s turn especially is reminiscent of London Zoo opener ‘Angry’, which serves as a reminder that it’s been quite a while since that album was released. At the time its portrayal of a crumbling capital was brutal enough in its realism. Four years down the line and the economic crisis, which was just beginning to make its presence known as London Zoo was released, is crushing downwards with far greater weight than most could have predicted, accompanied by a widespread political swing towards the right and brutal ideological reforms dressed up as emergency contingency plans. Given the sheer rage of this opener, the prospect that Angels & Devils may prove even more caustic than its predecessor is tantalising indeed.