A History of The Future. The Future becomes the present. The present becomes past. The past turns into a succession of years. Every, say, five of those years becomes an anniversary. Until we’re left looking and listening to – at what was very much at the time – The Future. This future sounded nice, interesting, a bit mad – all good. It also had a lot of the past re-shaped. This was what The Future was going to sound like: Fragments of the past chopped up, played about with, thrown into new forms. We had become accustomed to shock and wonder over the first half of the 1980s, and here, around about the midway point, was a new album. A manifesto (they were named after a 1913 Futurist manifesto). A new beginning (all the players had done time in showbiz – super-producer Trevor Horn, music journalist and ‘ZTT tea boy’ Paul Morley, composer Anne Dudley, engineer Gary Langan and programmer J J Jeczalik). Most of them had already worked together on Yes’ 90125, ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love and Malcolm McLaren’s Duck Rock.

Thrillingly inventive, reasonably danceable and full of interesting bits to laugh, love and dance to. Wrapped up in an enigmatic cloak of masks and spanners, essays about art and sculpture – a slightly sinister shroud for the people behind the curtain.

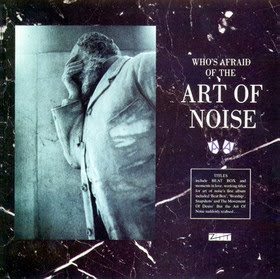

The fivesome were initially keen to be a non-group, hence the pictures of statues and the press shots with masks in scrap yards. There was no front-person, no lead singer to focus your attention on. Essentially the front for new technology, it allowed that old muso adage of letting the music talk for itself (man) and leaves it free of being carbon dated by whatever haircuts or snoods were du jour back then.

It was an extraordinary moment in pop music in general. Few people had harnessed the true potential – or could even afford – the Fairlight synth, with the likes of pop-boffins such as Peter Gabriel, Thomas Dolby, Herbie Hancock and Kate Bush being a handful of the early adopters, however within a matter of months there was cheap home keyboard samplers ahoy that allowed you to say “Bum” and repeat it annoyingly in different keys, and it would also lead to an influx of uses from the likes of the dance set, inspired by the cut-up nature of sampling and before long the like of M/A/R/R/S and S’Express were owning the charts.

Art Of Noise, or in particular, Who’s Afraid Of The Art Of Noise, inspired a whole generation of dance acts that followed in the next decade or so – The Prodigy (who even share a writing credit with the band on ‘Firestarter’ after sampling the “HEY!” off ‘Close (To The Edit)’), Chemical Brothers, Underworld, Leftfield etc. It was also a key album for anyone interested in making music but couldn’t sing or because guitars hurt your hands. This was serious play. Excitement. Demented giddy anything-can-go excitement.

Of the nine tracks here, three key ones – ‘Beat Box (Diversion One)’, ‘Close (To The Edit)’ and ‘Moments In Love’ stand out. ‘Beat Box’ and ‘Moments In Love’ had their origins in the first release by the band, 1983s EP Into Battle With The Art Of Noise. ‘Beat Box’ had been originally recorded around the same time as the team worked on Duck Rock, and its monstrous crushing beat has since gone on to be something of a hip hop touchstone, and the single also claimed the No.1 spot on the American Dance Chart.

‘Moments In Love’ was a sumptuous elegant showpiece for Anne Dudley, engaging her classically trained skills for the least frenetic, but increasingly strange 10 minutes of the whole album. It’s 80s credentials exemplified by the knowledge that Madonna walked down the aisle to it when she married Sean Penn.

‘Close (To The Edit)’ was a distillation of ‘Beat Box’ into a single format. A single that could be played on MTV and, heh I’m showing my age here, The Max Headroom Show. With a repeated sample of the revving up of a neighbour’s VW Golf, and liberal borrowing from previous projects – the title was a play on Yes’ ‘Close To The Edge’ and also features a sample of their ‘Leave It’ tune, and the “To be in England in the Summertime…” was supplied by Jecazlik’s then partner Karen Clayton, who’d also rebuffed Martin Fry in ‘Poison Arrow”s spoken word moment. It reached No.8 in the UK in February 1985, leading the way for Who’s Afraid… to be snapped up by those who listened to the album medley on the b-side of the 7”. The sleeve of that contained a cut out voucher offering a then-colossal 50p off the album.

The rest of the album contains vignettes and tracks that have their origins on the Into Battle… set, mainly incidental music, or mediations of the themes already explored on the key tracks. ‘A Time To Hear (Who’s Listening)’ is more a collage of sounds and voices to enlighten the listener of what’s ahead and ‘Snapshot’ is exactly that.

Coming reissued and remastered, there’s a plethora of bonus features, with excerpts from BBC live sessions from the era, while the second disc is a DVD with short films, the videos to ‘Close’, ‘Beat Box’ and ‘Moments In Love’, some cinema adverts including a fantastic one with Kenneth Williams narrating. There’s also live footage from 1999 and 2000, almost a return back to the band’s post-Who’s Afraid… estrangement from Morley and Horn, when things went a bit tits-up and they started to collaborate with Tom Jones.

Now heading towards its 30th birthday, Who’s Afraid… is a brilliant racket of the then future that would enhance and influence the years ahead. For a band that never really quite got their due – the album hung around for a few weeks in the album charts, never getting higher than No.27 – this reissue re-establishes their aheadness and will continue to grow in stature as a key text of electronic music. Hey!