Sometimes music is here to help us readdress the everyday. Some people use music as pure escape, "taking drugs to make music to take drugs to" (as Spacemen 3 so put it). On the odd occasion it looks like an attempt to reframe our social landscape altogether, sometimes as an offshoot of the previous option when psychedelics are involved. 60s psychedelia in particular saw musicians in pursuit of "the truth" via a combination of hallucinogens and rock music, as seen through groups such as the 13th Floor Elevators.

Less poet-as-prophet and more musician-as-alien-angel, 60s jazz legend Sun Ra reaches out for that psychedelic truth. Decked out in gold-lamé and embroidered turbans, he and his ever-morphing Arkestras would have appeared seemingly anachronistic, like the figures in Ancient Egyptian murals that the superstitious think were alien visitors to ancient Earth. He also combined this element with the message that he was from Saturn, and that the people of Earth were at risk of falling into chaos. Despite its grounding in mythology and science-fiction, the possibility is undoubtedly there, as a constant and very human concern. So from all this, comparisons between Sun Ra’s persona and that of David Bowie’s ‘Five Years’-era Ziggy Stardust can be drawn (though admittedly Sun Ra was the first to embody this concept).

Both personas are archetypal outsiders or "others" from Outer Space, with ambitions to mould Western pop culture to some extraterrestrial ideal or utopian vision. There is a similar insistence on the integrity of these personas by their inventors or inhabitants, to the point where it seems that they have convinced themselves of their own story. But while Bowie’s persona of Ziggy Stardust never took over completely, Sun Ra fully banished the man formerly known as Herman Poole Blount. Sun Ra’s appearance could be misjudged as frivolous artifice, however, with his wonderfully garish Arkestra. But while Bowie arguably falls more towards the side of camp, Sun Ra’s mythical performances are interpretable as an expression of a different kind of alienation, that state of a black man who grew up in one of the most racially segregated parts of the USA – Birmingham, Alabama.

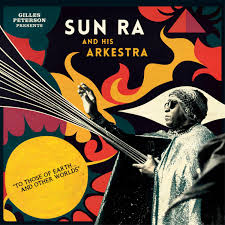

Sales of Sun Ra’s records were sporadic and many of his carefully self-designed pressings sometimes went destroyed, thus making his music difficult to track down today. To Those of Earth… And Other Worlds in particular was retrieved by Sun Ra archivist and ex-Arkestra percussionist Michael D. Anderson, who took it upon himself to provide a storage space for his numerous reels and tapes. What’s novel about these recordings in particular however, thanks to Anderson, is that they come directly from the original recordings and aren’t reissued from old LPs. Now, stuff like this usually only appeals to audiophiles, and one I am not, but I’d be an annoying contrarian if I said that these didn’t sound more nuanced than other Sun Ra recordings. This too is a compilation, and the question with every compilation is: is this a seamless and comprehensive listen, or does this sound like some cobbled together Spotify playlist?

This compilation is not an easy place to start off with as someone who has no idea of Sun Ra’s vast musical output. The different points in Sun Ra’s career aren’t easily charted on this record; it’s in no chronological order, but then Sun Ra’s trajectory never was straightforward. Quite considerable, really, is the fact that he was composing seemingly non-stop from the mid 50s up until his death in 1993. Sometimes he worked his vision to a big-band, other times it was more outlandishly expressed, but it was never apparent that he sought to contrast his later work with his earlier work. The organising of Sun Ra’s music here is more like a film with staggered yet complimentary scenes, than a coherent and fluid sequence of events. With this compilation being a hefty double LP, this’ll be a fairly abridged take.

Recorded on the cusp of the 80s, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ sees the Intergalactic Myth Science Solar Arkestra quietly chant the phrase "without Prince Charming, there’s no Black Beauty". And in this fairytale collage, beauty and artistry are drawn away from associations with whiteness and the white face – an issue that remains in the 21st century. What makes this line potent however, is that it is carried along by masterful improvisation. This incarnation of the Arkestra are so relaxed in their competence here that they make it sound easy, which of course improvisation isn’t. Sun Ra proves self determination and creative control via example – it says "Not only do we claim that blackness and black artistry is beautiful, you can’t question it. Listen to this".

Not only is Sun Ra’s jazz "free" because of its emphasis on improvising, the man was one of the first to experiment with production and new electronics. Although known for being surrounded by the latest analogue synthesisers onstage, Sun Ra could also be seen to play with production styles that did not usually accompany jazz. Some pieces on the compilation are fully-fleshed and winding, while others are short and intermediary, tracks to express snippets of ideas. ‘Reflects Motion (Part 1)’ does this well, with the sound of a palm’s impact as it hits percussion embossed with drowsy echo. This particular track might not work as a standalone, but like shorter tracks on many a jazz album it provides a segue between the longer tracks.

‘There Are Other Worlds (They Have Not Told You Of)’ is a little Connan Mockasin when he is Faking Jazz, and its fade-in is quietly brilliant. It sounds paranoid (but a natural flavour of paranoia that you can handle, like when you wake up disconcerted from a nightmare and you have to read for a bit). The track can also be found on the 1978 LP Lanquidity, but if this isn’t high-definition enough for you then you’ll be happy to hear it again on To Those Of Earth… And Other Worlds.

What’s really odd about Sun Ra is that, bar some late 70s keyboard freakouts, his music did not become progressively unconventional over time. So very unlike then Miles Davis’ gradual plunge into bizarre but aptly co-ordinated fusions of jazz and funk and rock (see his 70s Big Fun and Bitches Brew). To Those of Earth… And Other Worlds might sound disjointed, but then Sun Ra never seemed to care about genre or whether his music behaved according to rules or not. It’s this genuine disinterest in one’s past legacy that makes Sun Ra’s music sound genuinely chaotic. And all the better when Sun Ra adopts role as gospel preacher over the chaos.

The most cutting delivery of Sun Ra’s message here is in the mantra of "somebody else’s idea of somebody else’s world is not my idea of things as they are". This, of course, being the entrapment that anyone feels if they can’t steer the course of their own social reality. Sun Ra and his Arkestra would have felt this intensely of course, for reasons discussed. But far from being a pessimistic acceptance of a dysfunctional country, it is a positive declaration of independence from it. By standing apart, Sun Ra creates his own cultural sphere, one that has only grown further as musicians continue to interpret his message, now becoming a broader concept known as Afrofuturism. Another important thing to take from Sun Ra is his insistence on creating really contrary, surprising yet playful music. Behind the costume or ‘outsider-drag’, Sun Ra’s many Arkestras consistently embody a sincere drive to captivate an audience of stunned Earth-people. There’s only so much that can be delivered through a line or phrase alone; when this is accompanied by subtle, emotional music, this works as well as the headiest polemic.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/18935-sun-ra-and-his-arkestra-to-those-of-earth-and-other-worlds-review” data-width="550">