The limitations imposed by lockdown on studio spaces confirmed, once and for all, that making do is often a byway to going further. Take Amsterdam producer and musician Stan van Dijk. Mangling the lines between Brainfeeder-adjacent jazz, hip-hop and mutant electronica, his debut album takes ad hoc home recording to heady new places.

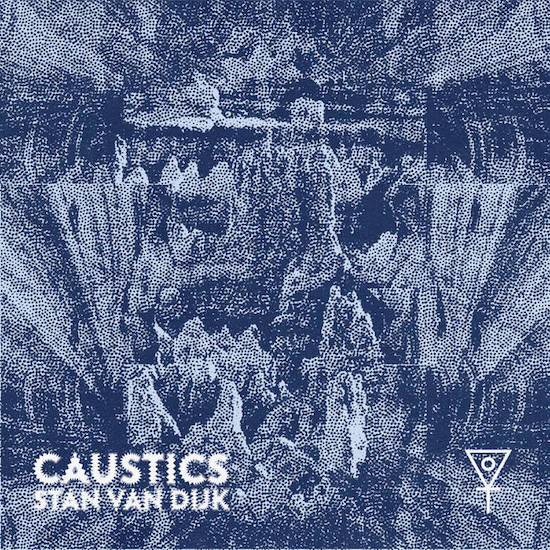

Titled after the optical phenomena whereby envelopes of light rays are reflected or refracted by a curved surface or object (think sun rays sparkling on a sea floor) Caustics began with van Dijk sketching on piano alongside saxophonists Ryan Whelles and Adriano Canetta. Steadily filtering the influence of Flying Lotus and fellow Dutch producer Jameszoo, Brazilian music and jazz of the 1950s and 60s, it took form as a full-blown prismatic release that’s fully fitting of its namesake.

Bar the sublime submersion of ‘Argan Voodoo’, Caustics is a straight-up polychromatic blitz. There’s ‘Arborio,’ an intricate astral mesh of digital jazz and raygun squelch. Steered by Whelles’ searing alto, it sets the pace for a record that flaunts without grandstanding. Nowhere is that more potent than on mid-album peaks ‘Damast’ and ‘Bosko’s Theme’. While the former marries Colin Stetson-like arpeggio squalls with plinking Rhodes piano (or in this case a Rhodes plugin, but who’s checking?) the latter is a magnificent tumult of tumbling beats, Thundercatian hyper-bass and Canetta on tenor sax.

There’s a wonderfully turbulent quality to even the more serene moments here. Much like FlyLo and his more forward-pushing peers, van Dijk introduces deft patterns that, rather than stand out on their own, function as part of a much fiercer current. With it, his brand of fusion burrows deep and feels, more often than not, fearless. Like tearing up staring at the sun, the extended chord shapes of ‘Giacomo’ feel crystalline. The rapid-fire phrases of ‘Musc’ meanwhile, are ecstatic and unnerving in equal measure, like sitting in on a Saturday night blasting Ben Frost on molly.

To call Caustics a kind of sleight of hand would be to reduce Van Dijk’s obvious flair as a producer, first and foremost, to something of a quirk. It’s not a quirk, nor a fluke, and yet one can’t help but feel a little floored by its ostensible status as a DIY album. As closer ‘Stew’ crests, Canetta’s tripped-out tenor taking centre-stage, setting and reference points fall out of view. Taking their place is the realisation that, for van Dijk, precedents and conventions are there mainly to be overturned and exploited – and how.