“Do not ask who I am and do not ask me to remain the same.” Considering the rate at which her music has evolved, and her recent refusal to be boxed in by stupid questions, it would seem reasonable to credit those words to St. Vincent. But that line comes from French philosopher Michel Foucault. The two share a fascination with power in its myriad forms, be they social, sexual, emotional, or financial; Annie Clark was reading Foucault back when she was writing her debut album, 2007’s Marry Me. Perhaps another Foucault quote stuck out when producing new album MASSEDUCTION: “From the idea that the self is not given to us, I think there is only one practical consequence: we have to create ourselves as a work of art.”

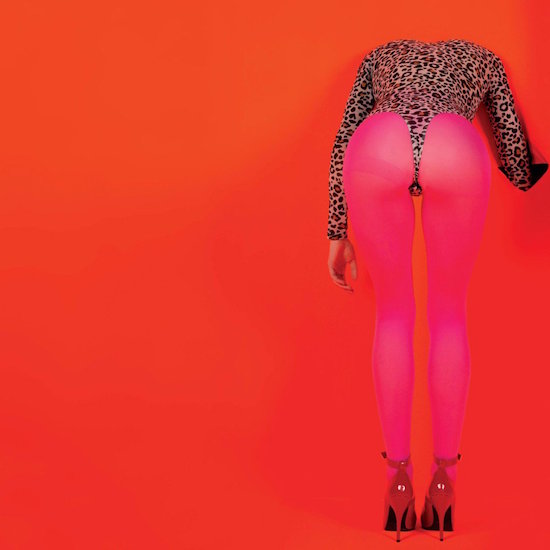

From the first announcement of tour dates, Clark laid bare the topics that had preoccupied her these last three years: power, objectification, and control over one’s own self and message. In the art accompanying the announcement, disembodied legs in stiletto boots stick out of a pink wall, equal parts absurdist and alluring. The album cover features the delicous buttocks of a woman bending over wearing pink tights and a leopard thong. In a video “announcement,” she approaches a garden of pink microphones and, rather than actually announce anything, coughs uncontrollably. Snippets of other videos released later found her reacting to cliched questions with faux earnest, with stickers on her fingernails spelling out F-U-C-K O-F-F-F. She conducted interviews promoting the album in a giant pink box, a St. Vincent sensory overload chamber, complete with pre-prepared answers to questions.

Two consistent messages stand out. First, we are not in control of our bodies once they are on display for the outside world – to the point that they’re broken down into composite parts to be consumed. Second, our meanings and messages are so often corrupted, spun together, and then unravelled societally that a major shift is needed for the artist to regain control.

By regulating the release of MASSEDUCTION, Clark has been able to shape herself as a work of art, harnessing the power the album can hold. But it’s clear that no power dynamic is as clean-cut as that might suggest. Even beyond the lyrical conversations of seduction and power, the album musically pushes and pulls in its hierarchy: a drum machine will dominate the mix, only to decimate and fall away, replaced by a new synth pattern.

On the title track, Clark conflates sexuality, need, violence and control into a tight ball of beguiling robot rock. “Don’t turn off what turns me on,” she insists, immediately after saying that she holds you like a weapon of mass destruction. She pairs those thoughts with references to Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady (an album about love and conflict for which the jazz legend wrote liner notes with his psychotherapist), Lolita (Vladimir Nabokov’s novel narrated by a man who becomes sexually involved with a 12-year-old girl), and The Boatman’s Call (Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ 1997 album driven by piano, equal parts romantic and sombre). In Clark’s intertextual world, every version of power intersects, a messy reality in which we each struggle to compose an identity.

Elsewhere, ‘Fear the Future’ extends that struggle into even the most private of spaces. “When the war started new / In our bed in our room / I come for you / Come for me too,” she calls, over scorched guitar, neon synths and retro electronic percussion. That sounds positive enough, but she continuously returns to a fear of what could tear even that apart, and winds up looking to some unidentified authority figure to provide clarity: “Come on sir, just give me the answer / Come on sir, now I need an answer.”

There are escapes from the typical power structures, most notably drinking, pills, and sex – but even these fail. “Yeah, I admit I been drinking / The void is back and unblinking,” she begins on opener ‘Hang on Me’. The hook to ‘Pills’, with its sing-song-y simplicity, reinforces the idea that society has given over its power to medicine to numb the pain. Later, on the beautifully crumbling ‘Young Lover’, she finds herself becoming that medication: “Young lover, I wish that I was your drug … I wish that love was enough.”

Musically, the album amps the eccentric electronic and new wave grooves that her 2014 self-titled pushed. ‘Los Ageless’ uses rubbery textures and punchy 80s drum machine to get at the showy, hollow tone of the city she’s stuck in alone. The girls aren’t only dancing in cages, they’re playing air guitar, their agency removed in multiple frames. Moreover, she herself isn’t just struggling with the lack of someone, but with anguish over the anguish: “How could anybody have you and lose you and not lose their mind too?” Meanwhile, ‘Savior’ echoes Prince with its funk guitar line, but pairs it with counterpunching electronic bubble and burn, the lyrics transitioning from dress-up games (she’s handed a nurse’s outfit, a teacher’s denim skirt, and a police uniform) to a refusal to be boxed into any single identity: “But that’s still not it / None of this shit fits.”

And none of it fits, in part, because she has seemingly lost so much. “I have lost a hero, I have lost a friend,” she calls out while wandering the cold streets of album highlight ‘New York’. Johnny pops up again, presumably the same entity as ‘Prince Johnny’ from St. Vincent and maybe even the John in the title track to Marry Me, but now he’s living on the street, the relationship strained in his mind by her fame. “You saw me on magazines and TV / But if they only knew the real version of me / Only you know the secrets, the swamp, and the fear,” she sings. It’s her most direct assessment of the difference between perception and reality, the struggle between assigned identity and personal definition, of the power of the other.

As the album comes to a close, Clark finds herself struggling with absence. The stunning, string-laden ‘Slow Disco’ is a tear-jerking elegy for the end of the night, and the best song on the album. As the disco ball spins, she’s already exited the scene: “Slip my hand from your hand, leave you dancing with a ghost.” In one sense, the song could function as an artist going through the routines on tour and preoccupied with the “bay of mistakes” she can’t shake. Even the sweetest music, and ‘Slow Disco’ surely qualifies as that, can’t save her from the “slow dance to death” – a line a pitched-down vocal repeats as the song ends.

“It’s not the end,” Clark repeats in a hushed croon on closer ‘Smoking Section’. That might seem like solace, but it only comes after she weaves a set of other, morbid ends. In one, she sits near some smokers, hoping a spark will set her ablaze; in another, she feels like an ocean and waits for you to drown; in a third, she stands on the edge of a roof, threatening to jump “to punish you.” And at every instance, she merely repeats “let it happen” and asks, “What could be better than love?”

MASSEDUCTION defies expectation, defies definition and defies the very idea that definition can exist. It’s an album detailing the mess of identity politics and power structures, and yet it hits serious cohesive highs. There is no cookie-cutter remedy, no rallying cry, just a baker’s dozen viewpoints of the chasm where we once thought order, power, and meaning lived.