In the summer of 1977, like the best minds of their generation, the Mael brothers heard Donna Summer’s I Feel Love and found their own present work wanting. Swiftly radicalised, they began mouthing off in interviews about guitars being “passé”, and blagged an introduction with the track’s producer, Giorgio Moroder. Moroder agreed to produce the next Sparks record.

The twelve months that followed I Feel Love were a long time in disco years. Moroder had been played a remix of I Feel Love by the New York DJ and producer Patrick Cowley. Making liberal use of looping and reverb, Cowley unfolded that track’s energy flash into a fifteen minute cosmic juggernaut. Though Moroder was publicly dismissive of the mix, judging off No.1 in Heaven one can sense that privately the producer sensed the way things were going. You can hear on the album a scale and ambition found only in the most forward-thinking of their electronic contemporaries. Cowley’s work with Sylvester is one example, Celso Valli’s production on Tantra’s astonishing the Hills of Katmandu is another (with its breathless yet mannered vocals, it’s possibly No.1 in Heavens closest sonic sister).

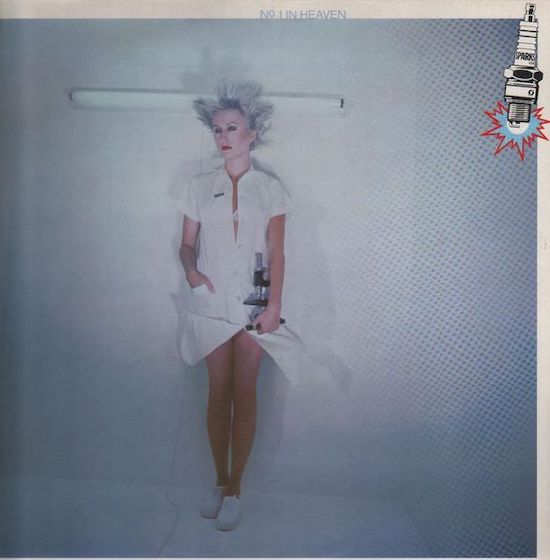

Moroder and Ron Mael crafted layer upon layer of sequencers and synthesisers, the only human musician on the record being the drums of frequent Moroder foil Keith Forsey. Russel Mael has never sounded better than here neither; his hysterical falsetto high in the mix. The introduction to Academy Award Performance is a career high point for Moroder; a twinkling soundscape of futurism rises then dissolves into urgent art-pop. Yes, big names like the Rolling Stones and Rod Stewart had incorporated disco flourishes for one-off hits, but Sparks were the first established act to utilise disco at full album length and in its most full-bodied, synthesised form. Sparks were a band that had always implicitly taunted rockist convention with their literacy, their camp, their anti-machismo. No.1 in Heaven, however, makes that critique explicit, offering glorious counter-revolution.

Sparks are regularly described as arch, wry, tongue-in-cheek; this has always been a complete misreading. Ron Mael as a writer certainly employers humour and surrealism, but as a device to write inventively and with real clarity about life, relationships and the human condition. This album is no exception, even following a loose lyrical concept – beginning from the perspective of sperm cells jousting for conception in Tryouts for the Human Race, and ending after death in the celestial with the album’s top 20 charting title track. Beat the Clock is a disco discussion on life passing you by, in search of lost time.

Though Sparks’ fellow cosmic disco pioneers would go on to influence acid house, it was Sparks whose influence was most immediate. ‘Low’ may have turned British listeners onto electronica, but No.1 in Heaven taught them how to take that to the dancefloor. The Mael’s keenly understood Europe’s post-Bowie cultural cachet, and lied on the record sleeve that it had been recorded in West Germany, rather than the actuality of sunny LA. Sparks would not only revive their own career but set a template for intelligent synth-pop that would be heeded by countless acts from Pet Shop Boys to the Human League, even Joy Division. “When we were doing Love Will Tear Us Apart” explained Stephen Morris, “there were two records we were into. Frank Sinatra’s Greatest Hits, and No.1 in Heaven by Sparks.”