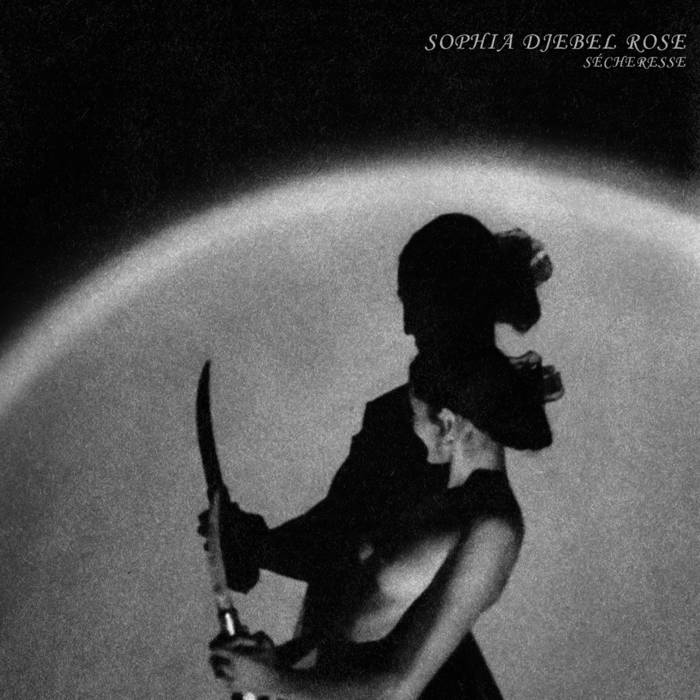

Sophia Djebel Rose first started singing in her early twenties while she was living in Lyon studying philosophy. A night of impromptu singing under a bridge with strangers coaxed the performer out of her, while a move to the bucolic pastures and volcanic mountains of Auvergne soon inspired the songwriter in her. Her second solo album Sécheresse, meaning ‘drought’ in French, is an accomplished and often moving avant-folk album that rummages in the soil of France in search of clues from lost generations.

Perhaps most extraordinary is her version of the traditional folk song ‘La blanche biche’ (‘the white doe’) a haunting and unsettling tale with its origins in medieval Brittany, with themes of transmutation, sibling abuse and cannibalism. Its verses are centuries old, though the rapacious brother Renaud is a true barbarist for our times. Clearly it’s a song that connects with the here and now, as the French folk quartet La Cozna also recorded a version last year, though Rose’s nine-minute rendition teases out the tension and fear and the graphic brutality of its conclusion, wearing the song like a freshly decorticated deer skin.

But her own songs hold up just as well, and they too contain deeper, often inscrutable meanings. The title track is an eleven-minute mystical lamentation predicated on a blissful drone, featuring a white-haired protagonist living in the “abandoned paths and the shadows of the ditches where the moss silently covers the echoes of forgotten revolts” – the French she sings it in is even more poetic. Dreams are summoned on songs like ‘Les Amandiers’ (or ‘the almond trees’), though there’s a pervading sense that dreamland intersects with the spirit realm too.

Death itself is never far away either: on ‘L’Homme au Costume Doré’, we’re at a graveside as the golden-suited man is laid to rest, and gold rears up again and again as a lyrical motif, whether its the pomme dorée of ‘Au Verger’ or the mention of golden shoes in ‘Les Géants’. If gold is a symbol of wealth and power and even vitality, then it’s also gnawingly transient. In this new age of Randian libertarianism, Rose seems to be concerned with the idea that we’re all connected to the land, the sea, the air, the universe and to history itself. Our individual parts in all that begin to look more and more insignificant as the album unfolds.

Sécheresse is a largely minimalist affair built upon the gentle picking of a guitar, with undercurrents of drone and the odd liberal helping of delay to bring a touch of modernity to the structures of these songs. It’s a stark, delicate environment which clears the floor for Rose’s dolorous vocals which, at times, are imbued with the kind of demonstrative pain you’d associate with cante flamenco. That modesty of component parts allows room for the performer to flourish, making these songs of life and death all the more powerful and affecting.