God, the saying goes, loves a trier. Which is lucky, because Billy Corgan, as many of his fans and critics alike will tell you, has been trying for years. Trying ideas, trying styles and, often, trying patience. His tenacity gets on people’s wick, sure, but it’s also something he doesn’t get enough credit for. The Smashing Pumpkins frontman is endlessly prolific (this is his fourth album in four years, alternating work with the Pumpkins with low-key solo records). He can be both musically awkward and extremely accessible – often on the same album – and rarely does whatever it is you think he should be doing; which for many includes going quietly away. Easy to admire and difficult to like, he’s the Mark E Smith of alternative rock (though there are Fall fans who will be out for blood at the comparison) and like that much-missed rock n’ roll curmudgeon, you’re equally likely to hate as love whatever he does next.

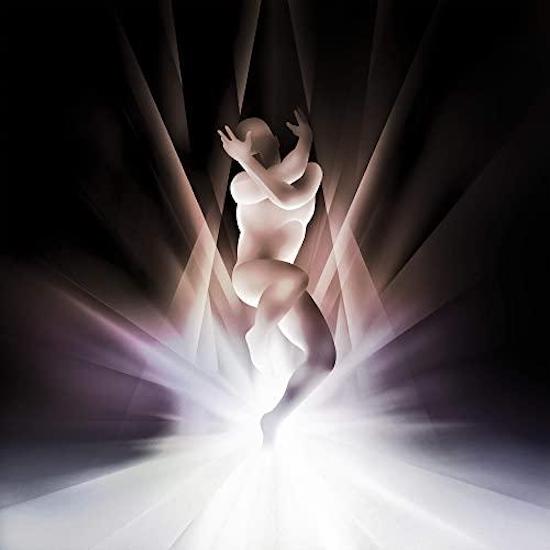

Which brings us to Cyr (pronounced, apparently, “seer”, or possibly “sia”), the eleventh(ish) Smashing Pumpkins record, and the second since Corgan reassembled his band’s classic line-up, bringing drummer Jimmy Chamberlin and guitarist James Iha back to the fold, alongside regular sidekick Jeff Schroeder. Corgan told Kerrang! that he approached Cyr as a chance to “make a Smashing Pumpkins album the traditional way for the first time since 1999”, though anyone hoping for some nostalgic 90s vibes is likely to be disappointed.

Making a Smashing Pumpkins album “the traditional way” doesn’t automatically mean super-accessible alt-rock bangers. In this case, it manifests as a 70-minute, 20-song double album of synthy goth-pop; something very few Pumpkins fans, and even fewer casual listeners, will have been clamouring for. Not that that’s necessarily a bad thing.

Corgan’s popularity may have begun with catchy anthems of alienation, but he sustained it by subverting the accepted way of the rock star. There couldn’t have been many fans of 1993’s sonically polished Siamese Dream who would have said, if asked, that they wanted their new favourite band’s next record to be a double album of metal epics, chamber pop and lullabies, yet 1995’s Mellon Collie and The Infinite Sadness was just that, and it made them, briefly, the biggest band in the world.

Corgan has never given his fans what they want, he’s usually given them what he wants, which when all goes right, turns out to be what those fans needed all along. Sometimes, as on Mellon Collie and its follow-up, Adore, that’s paid-off creatively, if not in the latter’s case, commercially. Other times, as on 2008’s hard-to-love Zeitgeist or his 2005 solo album TheFutureEmbrace, it has rather blown up in his face. It’s an admirable trait, but it means Corgan’s work can turn portions of his fanbase on and off like a lightswitch. That’s likely to be the case here.

There’s a lot to like about Cyr; honestly, there is. Corgan, pulling double-time in the producer’s chair, has given his latest record a very specific musical pallet: synths warble, buzz and wash behind his voice, and such guitars and live drums as can be picked out tend to be heavily processed, merging with the analogue keys and programmed beats. Much of the album’s feel comes from the backing vocals, provided by folk singers (and Corgan protegés), Katie Cole and Sierra Swan, singing in harmony and lending an organic element to the machine-tooled textures. When it works, it really works. Opener ‘The Colour of Love’ (note the British spelling) bounces and grooves, while the clockwork march of the title track channels Corgan-favourites Depeche Mode at the peak of their gloomy powers. The cybergoth of spooky Halloween anthem ‘Wyytch’ (the band’s knack for bloody awful song titles has never deserted them) twins razor guitars with the “eastern strings” setting on a mid-priced Casio keyboard to create something that is deeply weird, slightly naff and – against all expectations – completely great.

The sadder songs probably fair best here. ‘Dulcet In E’ is warmed by an acoustic guitar and a yearning, downbeat chorus. Those choral backing vocals make it practically glow. ‘Save Your Tears’ builds out of a spiky synth riff into a refrain that sees the three voices blending beautifully as they ask you to “swoon”. Honestly, you kind of do. It’s one of the strangest and loveliest corners of Corgan’s canon. It’s followed by ‘Black Forest, Black Hills’, an unsettling, mid-paced melancholy grind that finds Corgan “at the bottom of a boot-black sea” delivering a queasy and effective performance that’s nakedly about suicide and gives that subject the unflinching starkness it needs.

There is a problem, though. A fairly big one, actually. That specific musical pallet, while effective here and there, is pretty much the only sound on the record. The last time Corgan and co. tried for a double album they stretched themselves across a dozen genres and it felt like a journey. Here we have limited and muted colours scraped across a canvas that is simply too big to let them properly shine. Taken alone, these songs range from “really rather fine” to “ya know, fine”. Taken as a whole, they blur frustratingly together. Cole and Swan’s harmonies are a lovely counterpoint to the cyberscapes but they’re absurdly over-used, watering down their impact. Any of these tracks could have been retooled in any number of directions to provide some much-needed sonic variety. Corgan’s resistance to doing what everyone expects is admirable, but giving twenty tunes a tonal language that goes beyond consistent and out the other side into “samey” does decent songs a disservice.

There are Pumpkin fans and casual observers who will hate Cyr for what is isn’t (Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness or Siamese Dream), who will miss those buzzsaw riffs, liquid solos, and the effective use of one of the most astounding rock drummers of his generation, here mostly contained and looped. That’s fair enough, but it doesn’t make Cyr an objectively bad record. Not doing what everyone expects, not taking the creatively easy path (and, presumably, the commercially appealing one) – that’s actually admirable. Even kind of badass, in a contrarian sort of way. Instead we must judge Cyr for what it actually is: good intentions, interesting sounds, and a handful of great songs; compromised by an inflexible house style. It makes listening to the album from start to finish an experience that is occasionally rewarding – especially with a decent set of headphones – but ultimately, well … trying. And that’s a shame. It’s a curious mix of a commendable ambition to move forward and a maddening stubbornness preventing that ambition growing past a certain point.