In 1964 a special issue of the journal Anarchy was published, focussing on the city of Nottingham. On the back cover the journal’s editors quoted the American writer Paul Goodman. "The society I live is mine" – it reads – "open to my voice and action, or I do not live there at all." Inside, Nottingham writers – Alan Sillitoe, Ray Gosling, 14-year-olds from a secondary modern school – claim Nottingham as their own. They tell stories of struggle, hope and ambition; of ‘the Broast Street Beat Club’ and the Communist Party; and of the time in 1831 when Nottingham folk burned down the castle in disgust at the price of bread. There’s no special claims made for the city; no grandly romantic nonsense about its worth vis-a-vis other UK cities. Just portrayals of a city alive with jazz, inequality and badly designed roundabouts.

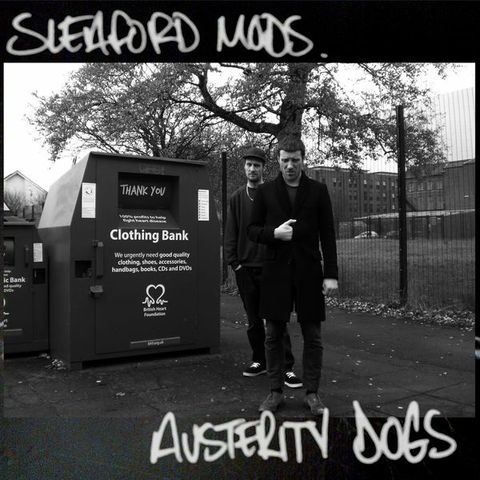

Nottingham’s not got much of a jazz scene any more, and nowadays its roundabouts win plaudits. But the inequality remains. And so – in the form of Austerity Dogs – does its tradition of speaking and acting in order to claim your society as your own. As quotable as Half Man Half Biscuit, as in thrall to the rhythmic force of language as the Wu-Tang Clan and as ‘wow, where the fuck did that come from?’ as Eccentronic Research Council, it is – like all those things – a brutally brilliant slice of working class culture.

When I say culture, I don’t mean something that can be packaged up and sold back at people so they accept their own inferiority. Austerity Dogs isn’t "we’re all in this together" claptrap, nor some expensively educated pillock holidaying in other peoples’ poverty like they’ve never heard ‘Common People’. Rather, it’s soaked in the impossible realities of the everyday, and it reworks that into something truly astonishing. Each song is a stream-of-unconsciousness from the collective dream-time of the dead-end worker who’s pissed off with his boss, pissed off with shit drug dealers, pissed off with aggro cunts in clubs, pissed off with "Brian Eno – what the fuck does he know?" It’s Chris Morris with a class consciousness, laying bare the surreal tapestry of horrors that face the working class in Britain today.

Sonically, it’s monotonously one-dimensional – rough, looping basslines and cheap beats come on with the demeanour of a theatrically disinterested Year 10 half-arsedly playing badminton in a PE lesson. ‘My Jampandy’ loops a two-note bassline for its entire duration; ‘Showboat”s riff is like Skrillex if someone pinched his LFOs. It’s all absolutely brilliant, and you’ll not hear a more unsettling piece of music than ‘Donkey”s dystopian half-hop all year. If heavy metal and techno were informed by the heavy machinery of fordist production, Sleaford Mods replicate the drudgery at the bottom end of the postfordist food chain.

It’s in the lyrics – and their delivery – that this album really stands out, though. In her book Revolting Subjects, the sociologist Imogen Tyler shows how tabloid hate figures (the poor, immigrants, Roma, single mums, etc) aren’t simply ‘abject’ but are produced as such: forced to live in squalor and then, as that squalor takes effect, demonised by the press and bourgeois small-mindedness/self-interest. Sleaford Mods know this too: on ‘Urine Mate’, frontman Jason Williamson tells us about seeing one of Nottingham’s better known alcoholics putting his bin out and "stinking of urine", whilst people from Mapperley Park (a fairly salubrious area) "point and laugh". Then, on ‘My Jampandy’, he tells how "cuts make people stink", whilst ‘Fizzy’ speaks of "work[ing] my dreams off for two bits of ravioli and a warm bottle of Smirnoff under a manager that doesn’t have a clue."

Williamson doesn’t always sing in the first-person, though – there are frequent changes of perspective in mid-flow. He’s a bouncer one minute, a punter witnessing misogynist violence the next. He talks about "music scene-think-they-ares", then speaks as if he is one (‘I’ll have a 32" waste in raw denim and stick ’em in the freezer’). This lends the record an uncomfortable cubism – a hotchpotch of half-remembered impressions from the night before coming into relief through the hangover’s haze: a disorienting miasma of contemporary bullshit.

Inevitably, Sleaford Mods have gained comparisons with Nottingham’s favourite anti-hero Arthur Seaton (indeed, Williamson has played Seaton in a Saturday Night Sunday Morning-inspired event and the video for new single ‘Mr. Jolly Fucker’ – not included here – was directed by Alan Sillitoe’s son, David). But where Seaton had that individualistic nihilism that so inspired Arctic Monkeys, Sleaford Mods know that you rise as a class or you don’t rise at all: "movin’ up in the world doesn’t mean using the lift, mate/What floor do you want?/Don’t mind me – I’m in the fuckin’ thing all day" (‘My Jampandy’). Perhaps the angriest words on the whole album (and trust me, that’s very angry) are reserved for "the cunt with the gut and the Buzz Lightyear haircut/calling all the workers plebs" and who’s just had a wage rise (‘Fizzy’).

So instead of Arthur Seaton, I want to suggest that Sleaford Mods carries on the tradition of another working class figure strongly associated with Nottingham – Ray Gosling, who passed away on November 19th. He writes a great piece in that Nottingham issue of Anarchy, but what I really remember of him is watching his BBC4 documentary Ray Gosling OAP and being utterly shocked: not just at the subject matter, but at the way he spoke about his life – and those of people like him. He wasn’t being spoken down to; he wasn’t being spoken about. He was speaking.

Sleaford Mods speaks too. "The society I live is mine" – this record says – "open to my voice and action, or I do not live there at all."