Archangel Hill, Shirley Collins’ third full-length for Domino and ninth studio album, greets us with a goodbye. And it’s not the first time ‘Fare Thee Well My Dearest Dear’ has headed a track-list for Collins: it opened Amaranth in 1976, recorded with her sister Dolly and then husband Ashley Hutchings. Now, gone is the baroque artillery of harpsichord, organ and sackbut, and instead attentive guitar arpeggios bustle around the vocal-line and play off this tale of death at sea with a knowing sweetness.

It wasn’t that long ago (2016) that Shirley Collins broke her 38-year silence. Lodestar was a stark comeback record wracked with the sharp pangs of May, the ache of reawakening. Anybody expecting warbly tweeness would have been abruptly put to rights by the opening track: a dirgy 11-minute four-parter complete with menacing hurdy-gurdy. Heart’s Ease in 2020 was a mellower affair: jaunty, macabre and flushed with summer wine.

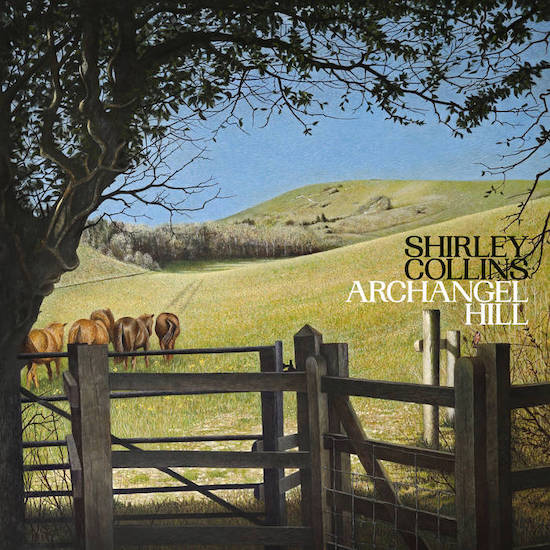

Archangel Hill has pockets of jubilance: ‘June Apple’ will have you jigging all the way to the nearest taproom. But its dominant mood is restlessness, yearning. And for an album named after a place (Mount Caburn in Sussex), it’s notable that the songs speak of departure, displacement, pursuit, kidnap, long journeying and delayed arrival.

“Some of the songs on this album I have recorded before,” Collins admits, “but I wanted to revisit them with this group of musicians”. Their familiar landmarks bring home just how much ground she has covered in seven decades, and how well the music responds to reinterpretation.

‘Hares on the Mountain’ featured on Collins’ first album Sweet England in 1959, then again on 1964’s Folk Roots, New Routes with jazz guitarist Davy Graham. And it’s a song that still intrigues Collins now, as she tells Jude Rogers: “You’re never quite sure what it’s about. Is it about women treading down on men or about something more magical than that?” This latest is the moodiest version yet, with Ian Kearey’s bottleneck guitar sounding woozy and besotted and unwilling to fall in line with the ruler-straight piano chords.

Nestled amongst these re-workings are some original compositions. ‘High and Away’ has lyrics closely adapted by Pip Barnes from an anecdote in Collins’ memoir, America Over the Water. And perhaps the album’s most striking moment: a live recording from January 1980 of Collins performing ‘Hand and Heart’ at the Sydney Opera House, shortly before the onset of the vocal dysphonia that would swallow her voice for the next four decades.

Collins’ soaring soprano always had the quality of unexpected music, like singing heard through an open window. It flew overhead: gorgeous and strange and necessarily borne away from us. To discover it here, framed between recordings made over forty years later, heightens the impact. But it also accentuates the new contours her voice has taken on since that time. It now sits closer to the gravelly earth and closer to our ears, more intimate-feeling.

The final track, ‘Archangel Hill’, is an original and the most discrete of the set. Collins reads a poem written by her father celebrating Sussex, while Kearey keeps her company on guitar and piano and curls of in situ wind graze the mix. If Archangel Hill traces a life-time of musical wandering, maybe this is a point of final arrival. A marker-stone placed on top of Mount Caburn. But I don’t think so. Collins’ father wrote the poem while he was in the Royal Artillery and its pastoral vision is glimpsed through the painful prism of distance. As Collins tells in America Over the Water, his homecoming was not a success. He soon left them and started a new family in the neighbourhood; they only saw each other once after.

I admit, I struggle with the reverb-laden guitar-line in this final recording. There’s a preening vanity to it which I can’t help associating with the absconding father, as if the inclinations to walk out on your family and to noodle away were somehow connected – which is ridiculous, I know. But the soft, metallic, doctored piano underneath is beautiful, like a clockwork marching-band going slowly uphill. Its patient tread seems to have miles left in it; promises to keep.

Describing what she wanted for the end of the album, Collins searches for the right word: “a recapitulation? an underture?” This desire to revisit, to go over old ground, has always been closely tied up with the most inquisitive and experimental instincts of her music. And with Archangel Hill, Collins continues to deliver on the title of that extraordinary record, Folk Roots, New Routes: finding old ways to look forward and new ways to look back.