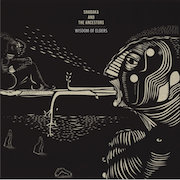

Though Shabaka Hutchings is perhaps best known for playing in Pete Wareham’s Melt Yourself Down, he has long been finding ways of escaping the trappings of their pop sensibilities – playing in the Sun Ra Arkestra in 2014 – and pushing himself musically. And on Wisdom of Elders Hutchings delves even further into the spiritual jazz that originated in part with Sun Ra, with the help of a new band in Johannesburg. And it’s a record that goes even further than his playing in Comet is Coming, another London-based project that refers less indiscreetly than Melt Yourself Down to Afrofuturist images.

Britain, at one point, seemed to be embracing spiritual jazz; ’60s musicians like Evan Parker certainly were. The artists involved (who, like in most jazz scenes, played together on each others’ albums) were primarily influenced by American spiritual jazz, and the scene was comprised almost solely of white musicians – the only well known exception being Joe Harriott, with his Charlie Parker-influenced spiritual jazz having been only recently discovered, with Hum Dono reissued in 2014. And so, generally speaking, British jazz was always likely to look more explicitly derivative of American jazz at this point in history, disconnecting from the ideas and Afrocentric stances held by Afrofuturism’s forefathers like John Coltrane, Sun Ra or Pharaoh Sanders.

Though obviously Sun Ra’s spiritualism was idiosyncratic and drew from European cult ideas just as much, it is best visually represented by the ideas he took from Ancient Egyptian mythology. Hutchings too shares an interest in the Afrofuturism that grew out from Sun Ra: in 2008 he played at the Pan African Space Station’s festival, which in a grander way is also an internet-based music platform, radio station and studio space that connects African music venues. If the name didn’t give it away, the Station cites Sun Ra as being at the crux of their mission statement: there ‘…are worlds out there that they never told you about’ and so the aim of the project involves connecting humanity via a ‘historic commonality… entangling experiences… [and] ideas of utopia and oppression, history and the future…’

So with this kind of project in mind, Hutchings travelled from the UK to Johannesburg to record Wisdom of Elders, and has himself explained that he enlisted the help of South African musicians ‘… to present the musical language that [he] normally associate[s] with [his] UK bands in the context of SA musicians and musical sensibilities’.

Although all of South Africa has a history of both race and class-based oppression, in recent years post-Apartheid Cape Town has become an international port, attracting Europeans. It is still surrounded by impoverished townships (which were formed under the 1950 Group Areas Act) and is much like Johannesburg in this respect, but probably feels safer to the international community that lives in the city’s centre. In an interview with The Guardian, Hutchings notes this differentiation, stating that ‘Johannesburg musicians have a restless energy. It’s a big city and not as picturesque or as tranquil as Cape Town…’. This restlessness is perhaps contributing towards a wider experimental scene in the city, for example the excellent imprint Mushroom Hour Half Hour, providing great improvised music influenced by European psych as well as jazz.

On record, this translates to the ease with which one can picture steam emitting from Hutchings’ band on Wisdom of Elders, with Mandla Mlangeni’s trumpet puncturing through ‘MZAWANDILE’’s shuffling pace at what sounds like, with a strange precision, exactly the right moments. It’s the album’s longest and most venturous offering, with several segments, mostly dramatic. Yet, the song’s departure is subdued in comparison, fading on just vocals and double bass. Without the rhoda piano on ‘JOYOUS’, it would be as if a dab of colour in the piece’s composition was missing; its rippling lightness providing welcome top end to compliment the double bass, so soft it seems barely there in the mix yet neither weak nor pallid. Rhodes pianos can sound clunky, though the band’s pianist, Nduduzo Makhathini makes it sound as if the tremolo is dripping from the track, its sustain given time to work its way into the piece. Makhathini’s piano, too, always sounds slightly removed and faraway – though more of an accent than as an afterthought.

There are points in which the looseness of play becomes almost familiar in itself, if difficult to follow melodically; to untrained ears the improvisation here can seem without any discernible, obvious features – similar to the feeling of searching for some landmark on which you can peg your sense of space or direction. The buzzing and seesawing of the brass on ‘THE SEA’, though fleeting, functions in this way: it’s a moment that sounds both like a fluke of improvisation and pre-mediated decision. As is often with free jazz, no one on this piece steps in the same river twice (to butcher a metaphor); if there is any repetition, it is brief and the band move on quickly to further create.

What cradles the album, however, makes each piece of sound part of the same project, is achieved by the band’s two percussionists – Gontse Machine and Tumi Mogorosi – who do not seem phased about keeping the rhythm and tempo together. In African music, different drum patterns and speeds often hold different significances (ones not always traditionally written down), and the drumming here draws more from modern jazz influences, with the experimentalism of Sun Ra’s spiritual jazz at its core. Unlike John Coltrane’s smoother playing, the kind found on Spiritual Jazz, the jittery and ecstatic players here repeatedly unsettle this piece of music, though the players here are sensitive enough to pick up on what must happen next. Wisdom of Elders shows Shabaka’s adaptability in playing, which stems it seems from an ability to unify and lead his own band. And more so than in Melt Yourself Down or Comet is Coming, it shows him truly breaking into a freer kind of jazz.