As a drummer and composer, Tatsuya Yoshida’s been making ridiculous, fiendish and frequently baffling music for more than 20 years. With Ruins, Koenjihyakkei and others, he creates dense, hyper-kinetic prog/math-rock, minimalist in instrumentation, maximalist in compositional complexity, accompanied by lyrics with no meaning beyond the phonetic. Aside from occasional diversions into keyboard-led prog or skronky-skree improv sessions with Derek Bailey, Ruins has largely been a two-person bass–drums clinch. But it’s never been the same two for long. One can only assume that the combination of an intensely intimate line-up and the demands of such garishly intricate music must be supremely stressful. Four official bassists have thus far twisted time and space in Ruins, the last and finest of whom, Sasashi Hisaki, departed in 2004. A number of bold deputies stood in on the ‘Bassist Wanted’ US tour, but Yoshida has mostly been mano a drumo as Ruins Alone.

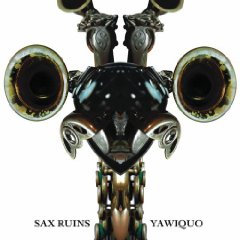

For a long while, it seemed as if Ruins were heading the way of their defunct monumental namesakes. Enter saxophonist/flautist Ono Ryoko (Acid Mothers, Ryorchestra). She is the resurrection, Yawiquo her progeny – 17 of the band’s classics, with brass in place of bass.

It is nuts.

Even for a die-hard Ruins fan, well versed in their brand of post-human ultra-nimble mathematical bludgeon, this is gobsmacking stuff. These songs are absurdly technically demanding, their relentlessly protean structures both fluid and boxy, their true form and purpose only ever apparent in glimpses. So far, so Ruins. The difference here is partially one of density – the multi-tracked horns rampage all over the frequencies with cacophonous but disciplined screeches and honks. ‘Komnigriss’, for example, formerly a spider caught in mid-scamper, becomes a small gang of Sonny Rollinses, out of their minds on uber-coffee and looking for trouble.

But what’s most immediately apparent is how naturally the faithful transposition of these tunes from bass to sax changes them from heavy prog into mutated big-band jazz. These songs seem instantly at home in a jazz context, as if Yoshida was secretly channelling Mingus all along. Within this aesthetic, their wild transitions, melodic oddities and restless nature seem more natural, less coldly calculated to disorient – even if that is their ultimate effect. But if this is a jazz band, it’s one from your most feverish dreams, one with the fiddly intricacy of Dave Holland’s Q&A, the cat-scraping intensity of Borbetomagus and the incoming-asteroid momentum of Naked City.

The song selection perhaps reveals something about Yoshida’s feelings about his own back catalogue – almost half of the tracks come from 2000’s Pallaschtom, five from Hyderomastgroningem, and one or two apiece from Vrresto, the 1986–1992 compilation and their cruelly under-represented apex, Tzomborgha. The extensive emphasis on Pallaschtom at the expense of even a single track from Burning Stone or Stonehenge is a little sad-making. Just imagine how irrepressibly joyful a saxified ‘Praha in Spring’ would be…

Tracklist geek gripes aside, Yawiquo is a wonderful thing, forceful, extrovert, and more than a little silly – an oft-maligned attribute in music, but in this context a fine thing indeed. It takes a lot of brains to be this foolish, y’know. It’s the musical equivalent of the long-lost-and-possibly-made-up episode of Ren & Stimpy scripted by Niels Bohr. And in terms of sheer sonic onslaught it’s possibly the most insane and extreme album Yoshida has ever made (or, at least, which hasn’t featured Keiji Haino).

However, the vacuum of new material is unsettling. It’s been seven years since the last album. Was the synapse-mauling Tzomborgha as far as the band could go in terms of complexity? Let’s hope that the bassist fiasco hasn’t ruined Ruins for ever, and that this is the start of a bold new era of ever-more abundant absurdity, rather than a novel one-off.