"It’s odd how placid a lot of music seems now," Sarabeth Tucek has gone on record as saying, "so washed out in sound and feeling. It’s like antidepressant music to take antidepressants to. I don’t really give a shit."

Ms Tucek may well be articulating what a lot of us feel, especially when facing the watery mudslide of gutless nu-folk and stage school singer-songwriters with nothing to say that the bedroom recording revolution of recent years has unleashed upon us. But it’s a particularly bold statement from someone who is herself an actress-turned-singer-songwriter, promoting a second album based around the sudden death of her psychiatrist father, and which she describes as "an impressionistic rendering of a time ruled by grief." We expect, then, that this will be the real thing: that it will cut through the glut of artless, overly polite acoustica that tumbles through our letterboxes every week (believe me, we at the Quietus do our best to protect you from 90% of this stuff); that it will sting our numb and jaded souls into some semblance of actual emotional response; that, at the very least, it will not pose around being pretty and feminine and sensitive, but will give it to us straight and neat and raw.

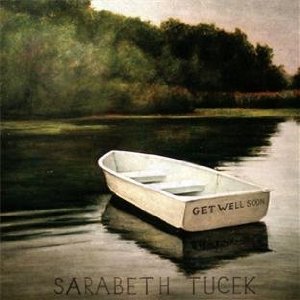

If someone is really baring their soul on record, it should feel to some degree uncomfortable to listen to; if it’s too easy, too pleasant, then either you’re not really listening or the artist is faking it. With Get Well Soon, the temptation to wince away from the intimacy offered is reassuringly ever-present. Sarabeth’s father suffered a fatal heart attack while out alone on a rowing boat on a lake; the cover of Get Well Soonis a painting of an empty rowboat floating on just such a lake. But the record itself is never a straight narrative or concept piece; rather, it builds itself obliquely around this ordinary tragedy, creating a flow of haunting images that almost but don’t quite add up, steering you in a certain direction but refusing to surrender their story entirely.

Indeed, many of the pieces here are mere sketches, such as opening number ‘The Wound And The Bow’, a vignette so fragile you have to strain to hear it, Sarabeth’s high, keening vocals almost slipping away behind the halting strum of her acoustic guitar. That voice is strengthened with heavily gated reverb on the next song, ‘Wooden’, an edgy lament for "memories fading faster than a speeding locomotive" and "running down to the lake, to watch you fade in the boat." But it’s still a shock when, two minutes in, distorted electric guitars and drums crash over the song like a tidal wave, sweeping restrained introspection away in favour of a quavering, agonised guitar solo that could have been beamed straight from Neil Young’s mid-seventies masterpieces like On The Beach and Tonight’s the Night, albums so loose, raw and sloppy that Young’s record company initially refused to release them after his AOR hit Harvest.

But it’s records like these – Young’s ‘Ditch Trilogy’, Big Star’s equally harrowing Third/Sister Lovers – that Tucek is drawing inspiration from, rather than the easy-going Harvest or the mellow, early Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Carly Simon albums that so many of her peers seem to be grooving on. And, listening to ‘The Fireman’, I’d add the consistently overlooked LA songwriter Dory Previn to Tucek’s forebears as well. Like Previn, Tucek brings just the right balance of personal confession, objective distance, sardonic humour and ruthless psychological precision to her analysis of the father-daughter relationship (something Previn returned to compulsively, though in her case this was based on her father holding his family hostage at gunpoint for several days).

Tucek and producer Luther Russell show admirable restraint in the arrangements too, mostly paring everything back to acoustic guitar and piano so that when electric guitars and drums do enter the mix the effect is all the more powerful. The country-tinged melody of ‘Smile For No-one’ could have proved too syrupy if dressed up with strings and choirs and slide guitar, though paradoxically this might have increased its commercial potential. But the music is never allowed to over-inflate the emotion of a lyric, and the pitfalls of self-pity and sentimentality are similarly avoided: "You are such a child; who ever told you beautiful things don’t die?", Sarabeth scolds herself on ‘At the Bar’, while ‘The Doctor’ admits to the shame of thinking ill of a recently-deceased loved one: "Cut from me the part of him that was so mean and cold."

And, ultimately, there is recovery, and moving on. "I am adjusting to the light," Tucek admits finally on ‘Rising’, which contrasts a dream of trying to hold her father safely above the rising waters with the rising sun outside her window at dawn and being able to rise from her bed and face the new day. And the title track, which closes the album, is the most stripped-down of all, yet is also the record’s most hopeful and uplifting number. "I knew I was sad, I recognised it was bad, but now looking back I see my mind it was cracked," she admits. Then, "Go help someone, get them well… it just takes time."

This determination to seek resolution is the stamp of genuine authenticity for me. Get Well Soon doesn’t romanticise or wallow in pain but catalogues it, accurately and unsentimentally, while knowing that the only value in such an activity is if it can be used to help someone else, that it’s in the act of reaching out that we get over ourselves, and our own loss. There’s a harsh reality in this record, and it remains real throughout, often raw, vulnerable and confused, but in proportion, never exploited or over-dramatised. Yes, it’s another introspective, acoustic singer-songwriter album, but it’s certainly not placid antidepressant music. This one’s for real. This one gets through.