One profound effect that downloading and blog culture have had upon the music industry is the reanimation of ‘heritage acts’ who, unable to protect their back catalogues, are no longer able to live comfortably on the proceeds of even extremely popular albums. Reuniting to tour, rather than to make new music, is currently the industry’s most reliable cash cow, and it satisfies an immense latent nostalgia in music consumers. But behind every great ‘Don’t Look Back’ show lurks a legion of 80s acts, crammed together on triple bills: ABC, OMD, Human League. Such endeavours turn musical history into a box of broken biscuits, the subtlety of the original flavours indiscernible in the crumbs.

But the taste of Sade is part of the national palate. The single most successful female artist the UK has ever produced, with more than 50 million album sales worldwide, she is emblemmatic of a certain moment in popular culture, one too often decried by critics – the birth of coffee-table music, of music as background. Hits such as ‘Your Love Is King’, and ‘Smooth Operator’ were the aural wallpaper of public spaces – clubs, bars, restaurants, shops – throughout the 80s, and remain regional radio staples. Though US critics and audiences embraced her, recognising perhaps more readily her love of 70s soul and the expert judgement of her tone, in the UK her seamless mix of soul, jazz and reggae came to represent the triumph of style over substance. Rather than exploring this new ambient soul form – later further developed by trip-hop, and in particular by Massive Attack and Portishead, both of whom have managed to transcend critical dismissal in similar terms – the UK music press generally failed to engage with her work beyond the most superficial level.

Sade has returned the compliment, eschewing the unending round of interviews expected of major-label artists. Despite her clear intelligence and the subtle understanding she has displayed on the occasions she has spoken about her work, her reluctance to engage with the press has too often been interpreted as having nothing to say. Her silence in public is matched by a certain distance in her art; Sade has often cast herself as observer rather than participant. She seemed happiest, especially in her early work, playing the club singer who watches, from behind the sad veil of her talent and beauty, a world of corruption and doomed love unfold. It suited her; it suited the idiosyncratic languour of her tone, the absence of attack, that generous little trill at the very end of her breath. Sade seems effortless – that’s her art. As she recently said to The Scotsman, "That’s the trick, like conjuring. You’ve got to allow so much to go in there. But it isn’t just your own. If it’s too attached to the performer, it pushes you away."

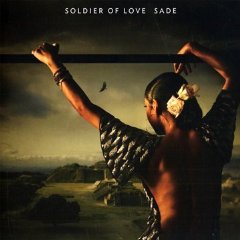

Though it doesn’t entirely abandon Sade’s long habit of detachment, Soldier Of Love is perhaps her most personal work to date. Her first studio album since 2001’s Lovers Rock, Soldier sees a great deal more first-person action than her previous albums. Now in her 50s, Sade might at last be entitled to a reminiscent tone, but the emotional palette of this album is, by and large, painfully present. "There’s nowhere I can find peace, the silence won’t cease," Sade sings on ‘Morning Bird’, a standout track whose spare piano part and dissonant strings accurately convey an unbearable absence. Loss, past, present and future, pervades this record: "I’ve lost the use of my heart, but I’m still alive," mourns the album’s title track over its sinister R&B, "still looking through the light to the endless pool on the other side."

Even ostensibly uplifting tracks like ‘Babyfather’ rejoice in the resolution of hard questions. Sade blithely reassures her daughter Ila (here on backing vocals) that, despite the end of her parents’ relationship, "the daddy love come with a lifetime guarantee". This song’s closest relative, both musically and lyrically, in recent pop is ‘To Zion’, from Lauryn Hill’s Miseducation Of album: a hymn to her son, in which Hill recalls wrestling with an unwanted pregnancy and the advice of friends and colleagues to have an abortion. There, as here, the joy of young life is all the more poignant for being the product of thought and difficulty.

Sade’s bleak take on relationships is more clearly in evidence elsewhere on the album, and however smooth the setting, her imagistic landscape is more jagged than ever. The lulling country twang of ‘Be That Easy’ belies the extremity of the experiences Sade describes: in an almost Bjorkish lyric, she compares her lover to a sky through which her house is falling. "That’s just like you to tell me I’ve nothing to fear; but I am a broken house… just falling somewhere," she sings calmly. As the song progresses, it becomes clear that calm is in fact resignation, and as clear as the skies may be, the house will one day hit the ground. It’s a powerful evocation of the inevitable entropy of relationships, and not for nothing: the following track, ‘Bring Me Home’, opens after the crash. Homeless and earthbound, Sade wanders heartbroken through an unfamiliar winter. "The ground is full of broken stones, the last leaf has fallen. I have nowhere to turn now," she sings.

Despite the frequent moments of desolation, there is much here to reward Sade fans for whom a chinkless surface is the primary pleasure of her work. Sade the band – its lineup unchanged since1983, with Stuart Matthewman on guitars, Paul Denman on bass, and Andrew Hale on keyboards – is on form here, substantially augmented by strings and brass (and, oddly, featuring video director Sophie Muller on ukelele). The sound is more naturalistic than either Lovers Rock or Stronger Than Pride, with Hale’s keyboards taking a back seat and, with the exception of ‘Soldier Of Love’ – which generously layers military tattoos over programmed drum sounds and a treated bass – a marked absence of strong beats. The band’s characteristically silky production ethic – simply put, a tonal picture built almost entirely around Sade’s voice – is once again deliciously on point. The record does have moments of misjudgement: ‘The Moon And The Sky’, being overladen, meanders where it should glide, and the odd doo-wop feints of ‘In Another Time’ seem a little out of kilter here. But for the most part, this is an album far too complex to overlook, and an object lesson – as if Sade fans needed one – in the guiltlessness of pleasure.