"If a sound recordist falls in a forest without pressing record, do they make a found sound?"

This re-engineered version of the oft-cited reality dilemma is the theme for this year’s Rum Music Library conference, following 2014’s smug solving of the question, "What came first, the chicken or the egg?" The conundrum was cracked by first transposing the question into musical realms to become, "What came first, the genre or the experiment?" From here the view swiftly emerged that anything embryonic will always precede any category created in wake of its development, hence what mutated into what has become classified as a chicken would have first come from an egg. It is hoped that all unwitnessed tree activity will be afforded the same clarity through a similar renegotiation of its, as yet unsolved, query.

However, the notion of a ‘found sound’ is perhaps more usefully considered here as a way of negotiating the kind of work this column covers, and even music as a whole. Of course, ‘found sound’ generally refers to field recordings – more often sounds of nature, but also that of urban environments and other so-called non-musical matter – but why not consider it to be the classification for all and any presentation of sound? Each recording that is intended for others to listen to suggests those involved in making it have found sounds worth the trouble of preserving and publishing. And by regarding music made with established instruments together with those releases risking a charge of being non-musical (such as field recordings and electronic experiments), we might untether ourselves from non-audible trivialities to navigate beyond the baggage of style and substance that can distract from active listening. Contexts of cult-like worship whose tribes duplicate their genres to death would be ignored, while the dull ‘sport’ of craftsmanship with its illusion that high-scoring playing skills will always be superior to simple experiments would become less relevant. Instead, through regarding a work as ‘found’ we can appraise its discoverer, the artist, as a curator of sound waves, delivering experiences.

By sheer coincidence, but as if to back-up these unfounded notions, this latest column includes an untypical amount of typical instruments. But whether bearing beats or birdsong, flute or a fox skull, one thing is consistent: each artist has carefully curated the presentation of the sounds they have found to reward its listeners with the kind of nourishment that only excursions beyond the expected can provide.

Hawthonn – Hawthonn

(Larkfall)

Phil and Layla Legard (the former a member of Stoke-on-Trent’s Ashtray Navigations) have a fascinating way of finding sounds for their first Hawthonn project. They combine site-specific field recording, "hand-crafted" electronics (including some determined by geographic data) and an aural form of scrying (a method initially described by Kim Cascone as "still, yet deep sonic surfaces, from which unheralded images can arise") to harvest raw material from which to derive their genuinely beguiling compositions.

Recorded between June and November last year, the results of their highly creative and focused methods smoothly usher our mindsets beyond our living spaces into more phantasmagorical realms. Hawthonn‘s hypnotic success is down to the way it blends recognisably rural sounds (wind, sea and bird song) and musical passages (accordion, harmonium and folk song) with the arc and flow of electronics, the distinguishing attributes of each coming in and out of focus, obscuring where one ends and the other begins.

The 16 minute opening piece, ‘Foxglove’, has the melancholic song of a black bird subjected to increasingly unnatural levels of reverb, a metamorphic manoeuvre that amplifies some of its natural nuances to hallucinatory effect. Meanwhile Layla’s mantric, languid lullaby along with a rattling of found fox bones somehow make the transformative passage feel smooth and safe.

Primed and fully under Hawthonn‘s spell, ‘Aura’ sees Simon Bradley’s cello get caught on a wailing wind weaving through a loose hymn sung over paranormal processed electronics. Later, the suitably named ‘Ghosts’ sounds like it was recorded in a long barrow – a spare, mournful theme on an accordion intruded on by restless wafts and whips that grow to almost violent proportions. While the album concludes with the 20 minute ‘Thanatopsis’ whose radiating, rising, distorted harmonium suggests a return to the surface, then fades to reveal the calm search of smooth sine tones heading for the sun.

Detailed notes about the sometimes uncanny compositional process are to be found in Hawthonn‘s accompanying 36 page booklet. It begins by emphasising their attraction to "the idea of making music that functions as a gateway for the imagination", but, through spelling out the detailed context that so strongly determined its results, risks giving its listeners too much specifics to ponder before engaging their imagination (as it can do so well). For this reason, I would highly recommend listening first and reading up later to ensure Hawthonn‘s most magical affects are fully felt.

Simon Whetham – What Matters Is That It Matters

(Baskaru)

What Matters Is That It Matters also feels situated within the liminal space between environmental sound and musical instrument. Here, field recordings, often of the elements, have their musical qualities emphasised – the sparsely used traditional instruments (what sounds like flute, kyoto, piano and strings) complementing the tonal values of wind, fire and rain. Coming across as neither symphony nor documentary, but sharing qualities of both, it very much follows its own inner logic to elegant and dramatic effect.

There is an outdoor Zen-like ceremony evoked by the opening piece, ‘Things Just Fall Where They Want To’, which drops a tentative flute near a crackling fire in a billowing wind. The devotional encampment gets dusted in silvery streaks, as a mysterious presence builds. The spell is then destroyed by the violent skies of ‘One Side Of The Border’, its choral traces borne on the cyclonic winds lead to a vast, open space, unpopulated save for an expanding song filling the area as if spilling from an abandoned radio to emphasise an absence.

With such a series of charged atmospheres bearing ghosts of human (musical) emotion, it is easy to imagine some kind of dystopian future. But perhaps that is a default projection of a Western angst onto the ambiguities of found sound. Instead What Matters Is That It Matters, with its vivid locations and metaphysical resonances, could easily be a requiem for something closer to today’s very real, ravaged homelands and the consequent plight of refugees. What is in no doubt, though, is the vivid textures and rich sequences Whetham weaves with sound to sustain a rapt attention and fire the imagination.

Emmanuel Mieville – Ethers

(Baskaru)

Ethers provides a set of bracing showers of audio that amplify the molecular motions of air and water, exploring its changing currents and conditions. For the album the French composer, who studied musique concrète at GRM following a spell as a sound engineer, wanted to "give an earthy quality, a dense texture to drone music, to lower it from the ‘skies’" – an intent initially belied by its title’s hint at the heavens and subsequent un-drone-like hyperactivity.

But, consistent with Mieville’s intent, Ethers‘ four sound works are very much grounded yet no less extraordinary for that. Each is situated within a recognisable vortex where the heavy roaring bluster, occasionally masking public speech and motor vehicles, initially reminds of tidal regions in inclement weather. But in Mieville’s studied hands the everyday violence of the elements is presented as abstract sonic expressions with constantly changing densities and trajectories.

Intriguingly, each piece has traces of sonorous, travelling tones that occasionally emerge out of the harsh noise weather to suggest a destination and avoid staticity, like on ‘Sur Le Pont’ whose suspended reeds builds a strong physical presence before it is overcome by a busy drenched dockyard.

The most rewarding aspect of Ethers‘ innovative concrète compositions is how the identifiable elements swiftly lose definition or take on new ones inconsistent with prior perceptions. Car engines become tidal washes, what first seemed like bowed strings could be the wheeze of heavy machinery, and the clacking of train tracks become thunder storms, to lend the listener a wondrous, hallucinatory perspective into the ceaseless activity in our midst.

Yui Onodera – Semi Lattice

(Baskaru)

Semi Lattice is named after an abstract structure used by architect Christopher Alexander to illustrate how systems with overlapping units enjoy greater varieties; apparently, important in urban planning for new cities to evolve more naturally. Tokyo-based composer Yui Onodera, who has worked as an architectural acoustic engineer, took inspiration from this concept when building the seven pieces presented here, each of which unsurprisingly feels more concerned with how sound fills a space as opposed to a timeline.

Indeed, each track could be imagined as a hanging mobile, but instead of multiple pieces flowing in a symmetrical circle, these have much more complex interactions with the air in which they are hung. Many of the pieces have a glowing drone emanating from the speakers, permeating the room with subtle, inner currents travelling and turning. The effect is more easily compared to light than sound or movement, as a brightness slowly grows and rises, choreographed to gradually transform its environment.

On the surface, Semi Lattice could easily be used as an ambient device, providing an audible form of feng shui, but that would be to overlook its deeper dimensions. Instead of a contrived, designer-y cool, the album is filled with a warm, exploratory sensibility. The first piece has a powerful unworldly aura, feeling neither synthetic nor organic, rough nor smooth, as it heats up without quite breaking into a boil. It is followed by sculptural percussion as creaks and clacks, seemingly breeze-born, dance unevenly around low breathing undertow. Later, on the longest track, a simple, short piano refrain is looped, reversed and delayed, to encourage clusters of saturating overtones to grow, turning repetition into constant change.

On Semi Lattice Onodera has created a set of seemingly minimal sound structures out of complex interactions that will effortlessly transform any room, while the details of their intriguing inner architectures only begin to become apparent through focused listening.

Colin Potter – Rank Sonata

(Hallow Ground)

A new solo album from Colin Potter is always something to be celebrated. The Yorkshireman who has helmed the experimental electronic label, ICR, since 1981, is much more often heard collaborating with a long-established network of sonic pioneers. Indeed, Potter’s associations make him perhaps one of the greatest navigational aids in modern, magical music leading to the uniquely creative catalogues of fellows like Darren Tate, Andrew Chalk, Jonathan Coleclough, Phil Mouldycliff, Michael Begg and Fovea Hex, as well as having served in surrealist soundmasters Nurse With Wound since 1991, for which he is perhaps best known.

Frustratingly Rank Sonata is his first solo long player in fifteen years if you discount the serial collaborations and sterling releases culled from Potter’s semi-regular live shows. And, as if to emphasise a difficulty in finishing his own productions, side two of Rank Sonata kicks off with a remastered track from that last solo LP (‘And’ from 2000’s And Then). But there is logic in the selection: its ominous stagger through subtle avant-dub inflections, ‘though perhaps not what you’d expect from an artist more often associated with long form immersive drones and synth alchemy, fits well into Rank Sonata’s refreshing focus on rhythm.

‘Knit Where?’ takes a diversion from ‘And’s strange gait into what sounds like an operating theatre. The humble pun of the title positions the invasive patter from the point of view of material being fed into a knitting machine – a play with scale as the miniature torture chamber produces violent rips, reels, slices and snips.

These two striking shorter pieces are merely the interval in the main rhythmic event, however. Side A and the last half of side B are given over to ‘A Wider Pale Of Shale’, almost half an hour of twilit tribal festivities. Slow-breathing accordion-like tones stretch under a delirious deck of choppy layers as mutated martial electronics mesmerically morph into showers of gamelan tones that sprinkle light into the track’s otherwise dark night tenure. Like an arcane gathering, the parade’s complexities are deftly shrouded in a sustained tempo, its polyrhythms sometimes inseparable as they rise and sink in tidal tones of static wash and fizzing waveforms.

While it’s closest comparison point is perhaps Nurse With Wound’s equally intoxicating rhythm-fest ‘Yagga Blues’ (that Potter made with Steven Stapleton in 1995), the odd yet addictive propulsions afforded by Rank Sonata very much march to the beat of a different, and delightful, drum.

Nature & Organisation – Snow Leopard Messiah

(Trisol)

Photo courtesy of Ruth Bayer

By 1994, Current 93’s sound had travelled from nightmarish sound collage to a particularly refined and idiosyncratic form of folksong. Working alongside David Tibet and mainstay mix master Steven Stapleton at such a time was Michael Cashmore, a guitarist from Walsall who was primarily responsible for the baroque folk arrangements that quickly became not only synonymous with the band but with the ensuing, so-called neo-folk genre.

Buried between two of Current 93’s most highly praised releases, Of Ruine Or Some Blazing Star and All The Pretty Little Horses, Cashmore, as Nature & Organisation, released Beauty Reaps The Blood Of Solitude. Developed with Tibet and Stapleton, it trod a similar musical path, and, on the evidence of this exquisitely remastered re-release, remains very much the equal to Current 93’s highpoints, but with a greater focus on musical composition and less literariness.

The gleaming beauty of Cashmore’s picking and strumming, recorded in such hi-fidelity as to seem at the end of your nose, is at the centre of most of the album’s songs, accompanied by stirring strings and bucolic flute and bassoon. Their style is epitomised by ‘Willow’s Song’ from The Wicker Man, the perfect cover version included here exploiting the joyous vocals of Rose McDowall while reaffirming the pre-Christian European pagan mystique the group cast so well. But such pieces are often alternated with short, ugly war-like passages of militaristic percussion, snarling guitar and feedback, that heighten the seductive power of the album’s more mellifluous movements. With each track purposefully segueing into the next the album is a highly cohesive, striking set that somehow finds jubilance and joy in sorrow and loneliness.

Less cohesive, but sorely tender, is Death In A Snow Leopard Winter, Nature & Organisation’s second album, that is also included here but remains as unfinished as when it was first released in 1998. Again mirroring Current 93’s direction at the time that had moved to the stripped-back piano of Soft Black Stars, Death In A Snow Leopard Winter is also made of melancholic piano arrangements with choruses augmented by simple strings. Tantalisingly, one continuously anticipates the entrance of a singer that never arrives on each instrumental (especially that of Tibet or Antony who collaborated with Cashmore on The Snow Abides in 2007 and whose own introspectively-poised piano compositions bear a strong relation to Cashmore’s and Current 93’s songs). But perhaps this absence makes the sodden sadness all the more haunting. In any case, this splendidly presented reissue is a very welcome reminder of Michael Cashmore’s deeply sensitive and richly rewarding musical fare, one that since moving on from Current 93 has become all too rare.

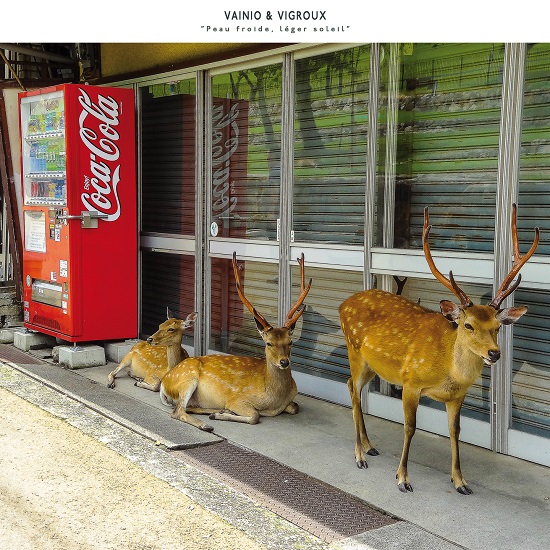

Mika Vainio & Franck Vigroux – Peau Froide, Léger Vigroux

(Cosmo Rhythmatic)

Cosmo Rhythmatic’s inaugural release from last year, Centaure, saw French composer Franck Vigroux tell a tale of technological cataclysm in sound and for this, their third release, he teams up with the esteemed electronic Fin Mika Vainio to explore deeper science fictions. On the face of it the pairing is optimal, they share a fascination for the noise/techno interface and its roots in the long established European avant garde (such as GRM for whom both has recorded), while both are equally happy to pick up a guitar (although it may not sound like one if they do).

Inspired to forge this release since first performing together in Paris in 2012, Peau Froide, Léger Vigroux is an artful assemblage of contrasting densities: the diamond-tight punch of its uneven electro beats invigorates while winding, vaporous tones travel mysteriously. This dramatic combination of hard, automated patterns and soft, brooding atmospherics makes it easy to imagine science fiction scenarios, and particularly one that explores the ‘what ifs?’ of artificial intelligence or cloning such as Alex Garland’s Ex Machina or Michel Houellebecq’s La Possibilité d’une île. For example, ‘Mémoire’s hi-tech, mechanical beats stubbornly stay on track while a curious aura builds to suggest a production line of memories and emotions, the bursts of distortion at the end perhaps emphasising a non-mechanical glitch in the process.

Plenty of chase rhythms and surveillance synths follow to suggest an action-filled escape but, possible plot developments aside, Peau Froide, Léger Vigroux‘s strength lies in its contrasts that persuade one to ponder possible tensions between machine and man. With authorship of so much technology-driven music arguably belonging to the machine (or at least its programmers) Vainio and Franck provide an exciting, emotional ride that can’t be artificially generated (yet).

Julia Kent – Asperities

(Leaf)

For her fourth album, New York-based cellist Julia Kent once again treats us to the unique emotional magnifications of her rich, dark bowing. But whereas her first two solo releases were based on a sense of place and travel, while the following Character took to describing a more introspective landscape, Asperities feels like it is negotiating between the two – the natural world and the inner world.

Kent’s customary process of layering themes and textures from her cello with percussive delay effects and subtle field recordings continues throughout Asperities‘ nine pieces, but the production often eschews the seductive and silky dance of previous releases and instead seems perched on the cusp of distortion. Even though many of the compositions retain all the tenderness and splendour we’ve come to expect, this album’s loud and raw exterior lends it a bracing sensibility that combines with Kent’s cathartic melodies to portray edgy, uncertain scenes of life against the elements. This is clear from the start as ‘Hellebore’s rough, weathered layers invoke a rumbling set of overtones in an aural equivalent of summonsing inner demons.

Complementing such tension is a consistently prominent low end. ‘Lac Des Arcs’ deliciously deep notes sink over tidal recordings to realise the beauty and power of a large body of water and ‘Empty States’ long and low bowing inspires an earthquake as a turbulent undercurrent battles with its melody and, arguably, wins.

The upped fervency and harshness of Asperities makes Kent’s refined, emotive melodies more charming in a way, and adds a new, more difficult dimension to behold – an encounter, like the outside world, that can be as bracing as it is beautiful.

Russell Haswell – As Sure As Night Follows Day

(Diagonal)

Of all three of Russell Haswell’s releases for Diagonal Records, As Sure As Night Follows Day sticks closest to the brief the label first gave him to produce a record "with beats". But, as with the first result, 2014’s 37 Minute Workout, it bears challenging, ruptured patterns that possess all the queasy properties of his previous productions. It is a perplexing and extraordinary result as the matter he’s working with – largely short, repetitive stabs – would seem so opposite to the freeform, searing and broiling noise of earlier outings.

Even the sparest, noise-free pieces, of which there are many, pose a similar, hardy challenge to scaling his noise walls. They tend to focus on a single hit, usually a kick, where each off-grid repeat offers a different perspective, feeling far from an invitation to groove and much more like an interaction with an abstract sculpture. They suggest a passion for techno music and its foundation in electronic sound, as if holding up their constituent parts to the light to better enjoy their various dimensions, uncamouflaged by their potential for pattern building.

Best of all though are pieces that weave Haswell’s more customary charged chaos in and around the heavy hits. ‘Hardwax Flashback’, its title referencing Robert Hood’s label of the early nineties whose ten or so releases also embraced the textural as much as the temporal, is the nearest As Sure As Night Follows Day has to an anthem. But it is one that instead of dancing is more likely to inspire a position of standing still in awe to its totemic power. Meanwhile, tracks like ‘Rave Splurge nO!se FM’ perfectly answer the question of what would it sound like if Napalm Death remixed Underground Resistance, albeit using an interface perhaps only Haswell could wire up.

By treating techno’s timbres as raw material Haswell has once again provided a series of tenacious terrains to traipse, climb over and sink into to transformational effect.

Jean D.L. & Sandrine Verstraete – S/T

(Rockerill Records / Instant Jazz)

The Belgium-based duo of Sandrine Verstraete and Jean D.L. combine the former’s poetry and tapes of field recordings and the latter’s guitar with film to produce performances somewhere in between cinema, gig and installation. But on S/T visuals are unnecessary, and would possibly be detrimental even, as their careful recording circumnavigates evidential experience for the much more elusive, interlinked aspects of memory and emotion.

Of the two long-form pieces presented here, the first bears more direct suggestions of recollections through Verstraete’s tapes. Their untempered static hiss of air carries undecipherable fragments of speech, the mechanical shuffle of train tracks, the odd cry from a child and traces of street-level noise as if from a distance in place as well as time. Bleeding through these unstable elements is the extraordinary emanations from Jean D.L.’s guitar, sometimes producing the merest smear of sonorous tones, elsewhere gradually building into portentous pools, covering Verstraete’s collage with sombre, emotive qualities.

The second piece is subtly smoother and clearer – a steadier, guided motion as opposed to a fogged drift – with a short poem relocating the listener into a downtime in a warzone. "Long breaks between attacks, … my breath indifferent, my eyes exhausted… We’ll never be the same." The few words make a startling difference, turning the ghostly, abstract glide into an anticipation of violence that is rarely met but keenly felt.

Both pieces make use of an inclusive mix where all the elements, both played and found, are afforded equal space and time to emerge and submerge. While this brings a lack of distinction to individual sounds, their confusion is what contributes so successfully to a sense of memories being transplanted, all put together so tenderly and with purpose as to be both a raw and refined recollection.