There’s a real case to be made for the idea of an album as a kind of toolbox. From this view, the tracks on a record, like different tools in a box, offer variations or alternate styles of approaching the same thing — generally speaking — or specific goal, if the project is more tightly defined. Like real tools: if you want to build a bench you grab your toolbox and head to the beach, cooler in hand, sunscreen in your backpack.

But really, it’s the utility or use-value that matters: you upload a record because it can do things, and the different files do different things that perform a categorically similar kind of action, etching feeling in the same affective zone. Evol’s parasitic 2013 LP Proper Headshrinker is the first album I thought of in those terms. It offers a potent methodology for everyday being, where its twelve tracks of psychoacoustic infection send you on varying but closely related tangents. Ten raving sound fragments with which to re-thread the fibrous material of your brain. Bach’s Goldberg Variations is an early entry in the form — an aria and a set of thirty variations.

Music as a toolbox offers you a more exciting way to exist without having to do any labour to get there — i.e. no falling in love, new job, money, whatever. It’s a cheat code to interesting feeling and the critical engagement that can arise from there, offering something adjustable and visceral to be used, deployed onto oneself or one’s surroundings. It can be minor or major for the listener — it can be their secret, in their pocket for special occasions, or it can coat everything.

We don’t usually expect records to behave like toolboxes, because music is predominantly marketed as the disposable soundtrack to consumption, in both the most mainstream and purportedly countercultural networks. Workers don’t throw away toolboxes — there’s good hits left in that hammer — just like I’d never throw away the two hours I spent reading Claudia La Rocco’s The Best Most Useless Dress on a boardwalk and watching it take on new spatial harmony in abundant clarity, things moving faster or slower, catching light for what felt like different, more profound reasons.

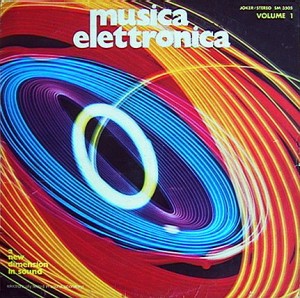

I’ve experienced Romolo Grano’s Musica Elettronica, recently reissued Keith Fullerton Whittman’s Creel Pone label — which celebrates "Unheralded classics of electronic music" — as a highly useful and well-constructed toolbox. The track titles and industrial design aesthetic of the cover very much lend themselves to that reading, too.

Similarly to a lot of musique concréte and electronic music in general, Musica Elettronica thrives as the product of a machine-tinkerer relationship. Here "tinkerer" carries perhaps a more feminised shade of meaning, working in non-predetermined becoming against the myth of the all-powerful, self-sufficient male genius.

In this tinkering context, space is opened up for powerful intimacy with machines, and vice versa. The music serves almost more to showcase the power of tools than write detailed compositions with them. The instruments were tweaked mildly, impulsively and uncomprehensively, based on the touch and feel of the knobs, and set running. The pleasure is evoked of getting to know how a new tool or system works, of testing one’s self in the process, too; feeling out capacities, predilections, mismatched or synced connections. The emphasis is on mutual instrumentality, machines doing to humans and us to them, and it remains unclear where each stops and starts because the exchange is materialising in atomic flows.

Tracks are let to blossom and bubble. They aren’t rushed past process toward assignment in another time or place, named and pushed aside, leaving vital scraps along the rim of the cookie-cutter (to borrow a phrase from Harry Dodge as cited in Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts.)

There is a useful tool-at-hand quality in these tracks: convenient and physical, ready for application. They bring the joy of trying on different items, test-driving. There is something refreshing or enervating about being able to mood switch as rapidly as this record allows with its short pieces. Draining and redirecting, emptying and diverting psychic flows, keeping the ecology healthy.

We can hear the record as a set of imaginations of the otherwise from the vantage of the labourer’s alienation from a single machine. There is not just one object being made in the factory of Grano’s work here: many systems, contraptions, media technologies — ‘Lens’, ‘Grip’, ‘Shutter’, ‘Zooming’, ‘Cartridge’, ‘Slot’ — are revving, clicking, or snorting side-by-side, ready for your walkthrough.

Like the scenes from Ghost In The Shell fixating on the beauty of sweeping urban viscera in decay, this record reminds us that the feeling of alienation from a machine-dominated environment can be pleasurable. There is an intimacy in a lack of intimacy; getting high off unrequited love; the melancholy of distance and proximity presented so indistinguishably.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/18598-romolo-grano-s-musica-elettronica-review” data-width="550">