Let us be done lamenting Róisín Murphy’s “inexplicable” evasion of commercial popularity over her two-decade career. Faced with a 2000s mainstream that loudly sided with the dinner-table joys of American Idol, Adele, and garden-variety indie fodder over the combative arrogance of Kanye and the seductive traumas of Lana etc, Murphy’s exhibitionist self-regard and visual expenditures-without-return never really stood a chance (Lady Gaga’s watered-down imitation, after all, only lasted a few years).

Where Gaga, Adele, and Simon Cowell were/are all on some level fundamentally oriented toward “consumer taste” (which is to say, the complacent comforts of selfhood), Murphy’s only ever allegiance has been to her uncanny ability to turn herself on: to new worlds, new identities, new spaces for aesthetic/affective production. We’re generously let in on the show, but don’t get it twisted—she’s the object(s) of attraction, the space of pure-and-playful potentiality, and she knows it. Consumption becomes addi[c]tive possibility assembled on a perpetually unstable plane, and ceases to be consumption altogether.

The trick of Murphy’s program of becoming-object is that she does so without any illusions of a unified subjectivity behind it all. Even a glam fem-bot like Grace Jones seemed to snarl from behind a relatively stable subject position—she didn’t have time for your shit; all Murphy seems to hold onto for ID is her box of interchangeable dress-up parts and that masterful smirk, which somehow puts across a sense of irony without smugness; knowingness sans knowledge. But such a project also brings with it obvious dangers—spend too long playing out over the edge of your subjectivity and the abyss will inevitably shoot a few looks back at you.

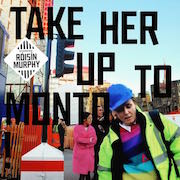

But Murphy’s work has never shied away from those unsettling tensions, and the decade since her time as Molokai’s autonomous-glam-puppet has only seen her push those anxieties into increasingly novel, uncompromising spaces. Last year’s Hairless Toys wore its psychological cracks as dexterous sonic architecture, assembling a dark, sinuous tour through her character’s existential distress with more epiphanic candor than she gets credit for. Borne from the same sessions, Take Her Up to Monto is the schizophrenic underbelly of Toys’ teary composure, and its much less interested in working through earthly lived experience than it is in traversing it.

It is Murphy’s submission to the materialist topography of subjectivity, a wholesale reverence for the objectified surfaces of “self” bordering on the religious/ridiculous that will ultimately define her contribution to The Gradual Collapse of Western Culture. “He had to find religion to measure his evil against.”

Take Her Up to Monto picks up this thread of psychotic materialism more resolutely than any of her previous works, its slick and occasionally menacing sonic eccentricities suggesting an acceleration beyond the subtle insecurities of Toys’ weightless melancholy toward some fucked-up inhuman liberatory chaos ahead—music for Ballard’s High-Rise, with all the energetic pessimism and anticipation that suggests. She faces up to the fact that she’s “fucked if I do and /I’m fucked if I don’t,” and subsequently elects to let the pretty garden grow wild.

The Eddie Stevens-helmed production borders on an unhinged assembly, positively obsessed with little hooks and bits of texture and percussion, jumbling them up Pablo-style into weird slabs of hummable abstraction held together by Murphy’s voice, which does more convincing shapeshifting than ever before. Inventive, deeply satisfying arrangements breeze by before being suddenly interrupted by what can only be described as…stretching; pop structures given room to expand, breathe, get some fresh air at cosmic altitudes, enough alien space for the fleshly semiotic meme-packages to see straight through themselves.

And yet Murphy’s words and intonations are not quite geared for flight from this place (granted, “Never again will I ever be grounded on Earth” and “humans are fucked”) so much as flight through it (“I get a little life as if by proxy”), via freed-up stand-in pieces. Pay close attention to materiality and you’ll notice it throws up all kinds of hallucinatory possibilities. “A sliver of cold breath has vitality.” We only go out from here, up toward more complex and psychotic layers of inorganic extension and organic intelligence, up toward “heaven.”