When wind and waves hit a coastline carved with weathered fissures and nooks, the noises made can bounce, echo and resonant in weird ways; the cliffs acting as idiosyncratic reverb tanks or sound mirrors to remake the soundscape in the same way the sea remakes the land. SIRÈNE was recorded by Robert Curgenven on a set of 16-foot pipe organs along the Cornish coast in the old churches of St Paul (Ludgvan), St Winnow (Towednack), St Uny (Lelant), St Wyllow (Lanteglos), St Cyrus & Juliette (St Veep). The pipe recordings are unprocessed – aside from minor EQing – and artfully layered with the hum and thrum of microtonal dubplates and ventilator fans, resulting in a record which is slow, thick and often overwhelming, where sound is a blurred map through Curgenven’s rich ancestral geography.

The recordings on SIRÈNE are as much textural as they are tonal, as the architectural creaks, drones and overtones of the pipes resonate through time-worn spaces. The breath-like rumbles of the old organs ripple out and back again with a gravitational pull, echoing the wax and wane of the wind and the waves across the coastline below. The weather seems to seep through onto the recordings: muted clatters of rain on cold slate roof and the clifftop wind creeping in underneath a creaking door. Then again, perhaps you don’t hear the weather at all: maybe its just that the recordings – particularly when listened to loud, on headphones – are so immersive, so transformative that the boundaries between what’s real and what’s imagined – what’s actually recorded and what’s not – become blurred and dissonant.

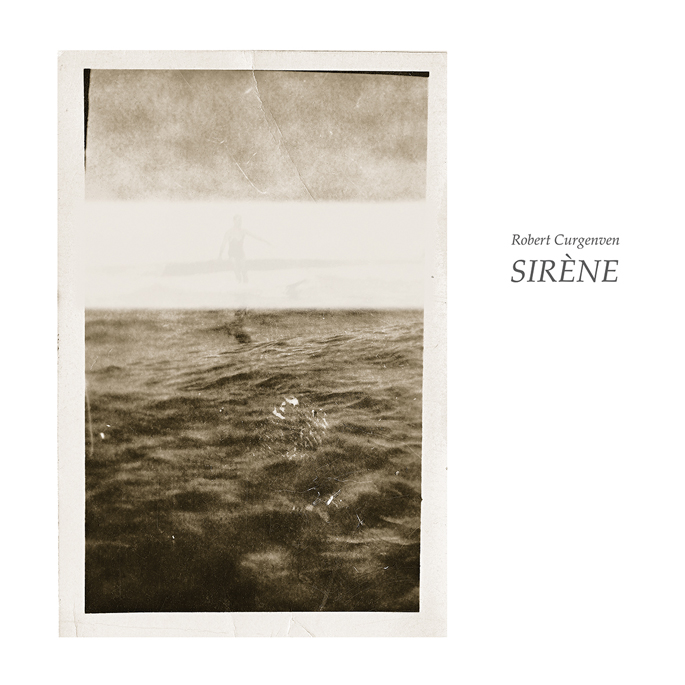

Whilst Curgenven is a Cornish surname (originally denoting people from the village of Crowan), Robert grew up in Australia, following his great-great-grandfather’s emigration in the 1870s. Curgenven retraced this route by moving to Cornwall a few years ago, and making the pipe recordings between 2011 and 2013. And in many ways, this record follows Curgenven’s own exploration of lineage and diaspora, particularly given that the churches (some of which date back to the 12th century) could have potentially been visited by his ancestors. These beautiful old spaces on the Cornish cliffs become echo chambers for Curgenven’s smudged impressions of the landscape, the sea, and his own personal histories. The pipes add a chance element to the recordings, acting as unpredictable resonators for the sonic memories of the space. And, perhaps appropriately, a box-brownie photograph of Curgenven’s grandfather surfing off Sydney in the 1930s adorns the record’s front cover.

Sometimes, the air seems so thick on this record that it becomes physical and real, like you can feel Curgenven’s weather fronts of sound diffusing through the churches, colliding and constantly being remade. The signal in these pipe notes abstracted from their source becomes difficult to decipher: the crackle of a field recorder with the gain cranked could be rain (or perhaps the other way round), and occasional human interference – footsteps, microphone scrapes, the pull of organ stops and clothing rustles – on the recordings punctures momentary lapses in this heavy reverence. You are reminded of the constant presence and intention of the recordist, and the periodic visits to the open churches by members of the public.

The glacial notes-between-notes of the first piece are underlain by subtle rattles of an electric hum, a seemingly disintegrating transmission of something or other, which reminds me of the undulating signal received from the (now fragmented) undersea cable at Porthcurno Telegraph Hut, which once stretched round the Bay of Biscay into the Mediterranean. The middle piece, Cornubia, is perhaps the most enjoyable of the lot, with a constantly unfolding wash of clear, hopeful tones which build like the fetch of a wave until they collapse in the idiosyncratic way that only pipes do: like the breath punched out of a lung, or the wind flopping out of a sail. For all the high concept and potentially impenetrable tones of this record, this track is often beautiful and uncannily human.

The third piece has the unwieldy title of ‘The Internal Meta-Narrative of Turner’s Tempest As He Is Tied To The Mast in Order to Create the Direct Experience Of The Drama Embodied Within A Snow Storm’ – [Wherein A] Steam-Boat Off A Harbour’s Mouth Making Signals In Shallow Water, And Going By The Lead. [Is Rendered By Virtue Of The Claim That] The Author Was In This Storm On The Night The Ariel Left Harwich’. Originally released on tape by The Tapeworm, the piece – a murky, granular suspension and release of tension – references the story in which JMW Turner allegedly tied himself to the mast of the ship Ariel during a nocturnal snowstorm in the 1840s, resulting in the painting ‘Snow Storm – Steam-Boat Off A Harbour’s Mouth’. It is thought that Turner made up this story, as no boat called the Ariel existed in Harwich at the time, nor did the painter visit the area. This segues into final piece, ‘Imperial Horizon’, where a 78 of <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._3_%28Beethoven%29" target=out">Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’, Symphony No.3 in E Flat can be heard muffled somewhere in the distance, providing a final, submerged coda of melody struggling to crackle forth from the ether.

Perhaps a straightforward comparison might be made between Turner and Curgenven in the way that their work evokes – in texture, tone and colour – abstractions of the natural world: in this case the power and unpredictability of the sea. More broadly, this reference to Turner and Ariel makes me think how the backstory to a record – the context in which it is placed by the press release, sleeve notes and the rest – influences what (and how) you hear. Perhaps this is a feature of many minimalist and drone records (and also the current swell of field recording pieces, as Derek Warmsley recently wrote about in The Wire), that the narrative behind the release has the potential to strongly shape how you perceive and experience the recordings themselves.

Part of the power of SIRÈNE is in the imaginary potential of sound abstracted from its source; and in the authenticity and certainty of Curvengen’s vision to record this set of old pipes. On this theme, we might ask whether this record have the same impact if it was revealed that it had actually been made in a studio with ProTools and synths? Perhaps – the sound has a strength of its own – but something of the resonance (whether real or imagined) would certainly be lost. How about if Curgenven didn’t reveal the (geographically and historically rich) details of SIRÈNE’s conception? I suppose this a wider question in lots of art: how far does a piece represent or evoke the experience of a place itself, and how much is projected by its contextual narrative – whether reliable or not – nudging you as the audience in a certain direction?

Regardless, SIRÈNE is a frequently beautiful, often overwhelming yet always intriguing record: dense, heavy and not to be taken lightly. Its rolling swells of metallic siren-song – all feeding back in some imagined, Turner-like whirling smudge of tone and texture – will not be for everyone. But, give this record some time and attention, and it will certainly give back.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/16179-robert-curgenven-sirne-review” data-width="550">