The story of Richard Skelton’s The Old Thrawing Crux is miraculous. It was made within sight of the Co. Galway landmark that gives the record its title. It was conceived for an improbable instrument, namely the ‘Carna’ clavophone, “a uniquely chaotic electro-acoustic device”, and was recorded direct to 2 ½ inch reel-to-reel. But, disaster struck and those reel-to-reels were, so it seemed, irreparably damaged. The work was abandoned, until a crowd-funding campaign paid for it to be restored using cutting-edge technology, the Punctus E.R.R. immersion system by Lightford Laboratories. You can hear this epic tale seeping into every inch of the music’s eroded edifice.

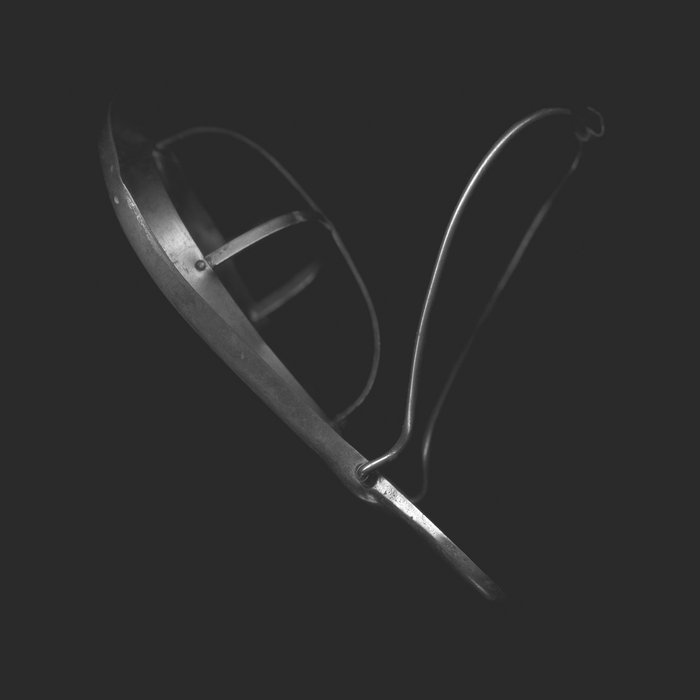

Or can you? The story of Richard Skelton’s The Old Thrawing Crux is just a story, and not all events and places in it are necessarily real. There probably is no ‘Old Thrawing Crux’ in County Galway and no ‘Carna’ clavophone either. Veracity doesn’t really matter though. Skelton calls them ‘sonic fictions’. Either way, the album sits among the most consistently captivating works the composer has committed to tape, reel or otherwise. The sonic equivalent of abstract expressionism, perhaps, where blurs of harmony and timbre swirl around each other and occasionally coalesce into fixed patterns. Music which moves like shadows gently leaping in the gloaming across a vast craggy landscape.

For much of the album, Skelton leans into the widescreen ebbs and flows that marked out his Landings era, but that music’s elegant melancholy is replaced by a more encompassing turbulence. Texturally, the vista of rusted steeples and jagged protrusions of his Moraine Sequence releases, and A Guidonian Hand, still loom. But the sharp edges have been smudged, and they feel less electronically triggered than before. The result is a volatile symphony, metallic and pastoral, geologic and seemingly charred by the burn of industry.

But for all the panoramic scope, it’s details and minutiae – subtle shifts in texture, miniscule anomalies and glints of tingling vibrancy – that take the album’s rich atmospheres somewhere more compelling than simply atmospheric. The way, midway through ‘agnition’, strident brass and strings gasp and give way. How the gulps of bass on ‘under glottal’ seemingly bend all the sounds around them. The skeletal piano following ‘wound dyer’s’ surge of electronic pulses. The flares of rasping tone amid the tranquil drift of ‘half notation’. The moment ‘autodidactic’ slips between romantic and martial.

According to Skelton, he gave the album a title with no existing referent so it could exist in its own world. Whether intentionally or not, it also draws attention to the fact that instrumental music often comes packaged with a narrative. There’s a reluctance to present sound without something to visualise alongside it. It’s often difficult to talk about sound without referring to non-sonic phenomena. But Skelton shows the ‘The Old Thrawing Crux’ is as complex as any real-world object. It might only exist in sound alone, but that doesn’t mean it’s not tangible.