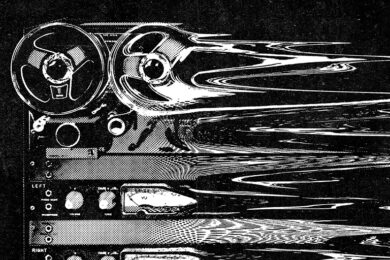

In the early sixties, the Peruvian composer José Malsio started experimenting and composing music with a pair of Philips reel-to-reel tape players. It was a private endeavour, these experiments were never performed publicly and any recordings have been lost. Malsio, who passed away in 2007, suggested they may have been misplaced in a house move. The only way anyone knows they happened is anecdotally, from Malsio, and his contemporaries, such as Enrique Pinilla, writing about them. What is documented of Malsio’s music are orchestral pieces rooted in acoustic instrumentation.

Despite no sonic record of his tape experiments surviving, Malsio is considered the first person in Peru to make electronic music. He was working with ideas that had started arriving in the country a few years earlier. In 1950, while studying in Paris, the composer Enrique Iturriaga met Pierre Schaeffer, and visited the laboratory of the musique concrète pioneer. Iturriaga was clearly moved, when returning to Peru in the mid-1950s he began hosting conferences and lectures, and premiering pieces by the likes of Schaeffer and Stockhausen.

Malsio and Iturriaga’s stories get at what Tránsitos Sónicos: Música electrónica y para cinta de compositores peruanos (1964-1984) – Sonic Transits – Electronic and Tape Music by Peruvian Composers (1964-1984) – a new compilation from Buh records, seeks to address. It collects pieces by Peruvian artists working in the overlapping fields of electronic, concrète and acousmatic sound, in a context where radical ideas about sound were circulating as much as sounds themselves. Most of these recordings remained in a rarely heard state, the majority never released on record prior to being collected here. As was the case across the globe, this music was being made without a clear outlet within the traditional structure of the recorded music industry.

These experiments were a rarefied pursuit, not just in Peru, but globally. They were made before wider access to music production technology allowed bedroom/garden shed/kitchen table experimentalists to flourish. They depended on institutions such as Groupe Recherches Musicales (GRM) in Paris, the Radiophonic Workshop in West London, Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales (CLAEM) in Bueno Aires, or TV and radio studios and universities and art schools that had the cutting-edge facilities needed. A challenge facing many of the composers working on these sounds in Peru was that, in the 1960s, such institutions didn’t exist in their home country. Most of the compilation was made abroad, the exception being Luis David Aguilar’s piece from 1978, which was made in Lima.

Some of the artists featured on the compilation strove to create a situation where their ideas could be appreciated, performed and discussed. For instance, as well as being one of the few witnesses to Malsio’s experiments, and a composer in his own right, Pinilla contributed to the heavy lifting of thinking about where these radical sound experiments might belong. In 1962, he wrote a newspaper article titled ‘Possibilities of Electronic Music’. In it, he concluded that this music was well suited to the realms of theatre and film. A similar conclusion to that which directed much action in the early days of the GRM and Radiophonic workshop.

Tránsitos Sónicos weaves an additional thread into a global story. In broad strokes, the seven tracks are most closely tied sonically to the artists surrounding the GRM (such as Pierre Henry, Luc Ferrari, Bernard Parmegiani and Beatriz Ferreyra). They explore sound as malleable material, where recording is the beginning rather than end of a piece of audio’s potential. But the compilation is more than just a Peruvian extension of a movement associated with Pierre’s Henry and Schaeffer. Through deft curation and chronological sequencing, we hear the music become increasingly distanced from the concrete urtexts they were inspired by.

The first four tracks experiment with magnetic tape. Cesar Bolaños’ piece is a whirl of overlapping voices, a slither of tape derived sound poetry. Edgar Valcárcel’s ‘Invención’ is more jolting. A zigzag of abstracted metallics exploring the sci-fi possibilities of tape manipulation, a trajectory followed with Pinilla’s squeaking, droning, squelching composition. This trio are especially poignant now. In the post-Disintegration Loops world, tape surface noise is often a fixation in itself, an overly used trope signifying melancholic nostalgia. For Valcárcel, Pinilla and Bolaños, playing with tape was a future facing gesture. A way to bring new sounds into the world rather than hear old ones decay.

Tránsitos Sónicos gets really intriguing in its second half. Alejandro Núñez Allauca’s piece is still rooted in abstraction via magnetic tape, but it’s imbued with a world building intent. Chittering bleeps melt away into a groan, which is equal parts bovine, automotive and numinous. Allauca was a generation after Pinilla and Bolaños, and his music marks a point where the compilation progresses into richer, more locally rooted terrain.

The following two tracks, by Arturo Ruiz del Pozo and Luis David Aguilar, see the techniques explored earlier on start to be applied to traditional Peruvian instruments. The latter’s work sounds remarkably current. Flute sounds twist through rolling drums and eerie ululations. Charged, turbulent, constantly warping, it feels as much in dialogue with Jon Hassell and David Toop as it does with musique concrète. An overlap which is endlessly intriguing and rife with possibilities that are still evolving in various underground music scenes today.

A piece by Corina Bartra closes Tránsitos Sónicos. She’s the youngest artist on the compilation, and her track points to a whole new world of possibility. Bartra studied composition and musique concrète courses in London. Her current work is focused on jazz and free improvisation. On ‘Aves en vuelo al sur’ we hear those two interests collide. It’s a mangled, folky lament where instruments and voice warp through concrete and electronic sounds in an unlikely yet effective convergence. In her piece from 1984, we hear a path opening out from the world of concrète music which has seldom been explored with the thrilling instability she captures here. It feels like music which could only have emerged from a singular time and situation, a perfect blend of influence and inspiration meeting specific technological possibilities and limitations.

The compilation tracks the local colliding with the global, a lens on ideas circulating and mutating. Its importance is reinforced when considering another pioneer of electronic music, Halim El-Dabh. In 1944, while a student in Cairo, El-Dabh used the facilities at a local radio station to edit, manipulate and arrange a field recording of a religious ceremony in Egypt into a new composition, ‘Taabir El Zaar’, also known as ‘The Wire Recorder Piece’. It prefigures many of the ideas that would later be explored by Schaeffer in what he’d come to call musique concrète. El-Dabh, meanwhile, would eventually move to the US, teaching at Kent State University and continuing to investigate electronic composition, remaining a part of a dialogue which, intentionally or not, he’d set in motion.

An awareness of El-Dabh’s work expands the geography and chronological borders of electronic music experimentation, and so does the new compilation from Buh. Tránsitos Sónicos tracks a period where new technologies opened new possibilities for sound, and those possibilities were explored with open-minds around the globe. Although facilitated by a mix of academic and broadcast institutions, it had and continues to have a resonance far beyond them, in noise and any form of music that relies on sampling or found sound. Expanding the archive of the voices doing the experimenting while de-centering it from Europe and North America can only ever be enriching. Tránsitos Sónicos helps stretch the history and terrain of this period of exploration, and reveals some of the avenues it opened up which perhaps remain to be fully explored.