The dissemination of stories on the internet, chopped down brutally because of twaddle believed about attention spans, can lead to misapprehensions about how innovation actually occurs.

The facts about Thomas Moulton are easy enough to ascertain, but don’t give you the whole story. He was born in Schenectady, New York State, in 1940. His family moved to Philadelphia and then he set up in California as a young man at the end of the 50s. He would be well into his 30s before returning to the City Of Brotherly Love to make his name. Long before this, however, he had his eyes set on being a radio DJ, but after a national payola scandal dampened his enthusiasm he became a buyer for a jukebox firm instead. He became involved in eight track stereo early doors, before working as a PR for James Brown’s King label and then becoming a record buyer for a department store. Moulton clearly had an ear for songs that were going to be hits, a good sense for trends, and understood the massive technological advances that were happening in the music industry – he just needed to create some luck for himself. And that is what happened on Fire Island.

Against his own better judgement Moulton, who was making ends meet as a male model by his early 30s, moved to Fire Island in 1971, which he considered a "Sodom and Gomorrah" full of "drug dealers and low lifes". (Even The Village People advised caution when visiting the Long Island, New York beach resort, saying: "Don’t go in the bushes, someone might grab ya, someone might grab ya / Don’t go in the bushes, don’t go, don’t go in the bushes / Don’t go in the bushes, someone might stab ya, someone might stab ya, yeah".) But actually what he found was something of a gay and lesbian friendly utopia. The resort features prominently in LGBT literature, art and cinema of the 20th century, with Rufus Wainwright claiming more recently in the 2004 song ‘Gay Messiah’ that when the homosexual saviour comes to Earth, he will descend from a star that looks like Studio 54 and alight on Fire Island. But back in 1978 when "the most famous nightclub of all time" opened its doors in New York for the first time, the musical power – even if little else – was flowing in the other direction, from the Sandpiper Club to Manhattan. The club acted as one of many social amplification points for the disco mix and disco extended remix, two revolutionary forms which Tom Moulton first designed on Fire Island in the early 70s.

It’s easier to get the full story when reading the liner notes from the CD version of excellent compilation Philadelphia International Classics: The Tom Moulton Remixes (strangely not available on the otherwise fabulous Special Vinyl Edition box set) or one of the few well-researched articles out there, such as the one posted by DJ History magazine. He told Bill Brewster that he devised the DJ mix after watching a substandard DJ at The Dinner Dance held at The Sandpiper Club. White gay men were dancing to black soul music at this club after coming back from the beach, but the DJ couldn’t keep them on the floor due to the lack of groove building potential offered by 7" singles and the temporal dissonance created by fading a new track in over the fade out of the last, beat mixing at that time being a pretty much alien concept. Speaking in the sleeve notes, he says: "People would leave the floor when that second song came in on top, because they’d hear two different things happening at the same time and it would ruin the vibe created by the first record. When I got home I wanted to do something that would elongate it, so people could at least start feeling what I feel about music – give them time to make that emotional connection."

Using a friend’s sound-on-sound tape machine and a record deck with varispeed, he spent 80 hours creating a 45 minute DJ mix with short, beat matched crossovers of three or four seconds where each track was playing simultaneously. He assumed that the revellers would be less likely to sit down if there was a continuous mix of tracks to dance to.

However, his tape bombed during the afternoon Tea Dance session that it was made for, he was told "Don’t give up your day job", and that was nearly that for Tom Moulton and the nascent mix revolution. (The story reminds me of what Grandmaster Flash told me about spending months locked away, working on his first ever mix using two decks and a home built mixer. After tirelessly perfecting the turntable techniques and cuts that would eventually form the basis of ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’ and that are still used by vinyl DJs today, the hip hop innovator played his mix to incredulous friends, who laughed at him so much that he nearly started crying and considered giving up his embryonic DJ career for good.)

However after initially hating it and openly mocking him, the club bosses did a U-turn after seeing a Friday night crowd go wild to the tape, and begged him to do one a week for $500 a shot. A bemused Moulton refused, citing the amount of time it would have taken, but they persisted and he agreed to do tapes for Labor Day and Memorial Day parties. Interestingly, it was the sheer time-consuming ball-ache of making these mixes that made Moulton go on the hunt for unreleased, extended versions of songs and instrumentals – anything that would cut down on the amount of time he had to spend painstakingly mixing between two totally different songs. While he realised that dancers would prefer longer versions with extended instrumental breakdowns, this was probably not the primary force behind him making these selections. It did lead directly to him making his first extended version, however, as there simply weren’t that many alternate versions of soul and funk songs available when he contacted the record labels directly looking for help. He created a totally new mix of ‘Do It (Til You’re Satisfied)’ by B.T. Express, boosting it from three minutes to five and a half – about the maximum that the 7" single played at 45rpm would contain at decent quality. Famously, the band hated it – until it became a dancefloor smash, and then started claiming that it was their idea all along. But from this moment on, demand for his remixing skills snowballed.

As befits such a progressive era for dance music, other big leaps forward were on the cards. The larger format single pressed specifically for the DJ was a common enough thing in Jamaican soundsystem culture but it was Moulton who came up with the 12" for American dancefloors. Except, as always, the real story is slightly more complicated. It was actually Moulton’s mix engineer José Rodríguez who pressed up the disc when he needed an acetate test pressing for Moulton but had run out of 7" blanks, so he used the only thing to hand: a 12" acetate. The moustachioed remixer said he would feel silly giving such a big record with only an inch of grooves on it to a DJ, so he asked Rodríguez to recut it and widen the grooves, which of course dramatically increased the dynamic range of the record. The 12" meant records sounded better in clubs, they could be longer, DJs could locate the instrumental breakdowns more easily without having to put markers on the vinyl – and all of it, as Moulton gleefully admits, was down to a mistake in the stock of raw materials, having to make do, and then feeling embarrassed about the end result. It was a case of accident triumphing over design, and someone being smart enough to spot an opportunity.

The luxuriously wide grooves contained on the Philadelphia International Classics: The Tom Moulton Remixes – Special Vinyl Edition box set are so good that I’ve listened to little else at home in the two weeks that I’ve had it. The sheer luxury and quality of this release demands extra vigilance for sweeping statements that bear an uncanny resemblance to things that either Swiss Tony or Alan Partridge might say. (In fact, I’ve just had to excise a description of the extended version of ‘Love Train’ by The O’Jays as being like a deep bath – "We’re down to the final lather… just relax… there’s a foamy bit on your shoulder – let’s make it even more frothy with a squirt of light lemon liquid.")

The box traces ten years (1972-1982) of remixes for Philadelphia International, starting with The O’Jays’ ‘Back Stabbers’ and culminating with The Jones Girls’ ‘Nights Over Egypt’. There are 31 tracks spread over eight discs, meaning the suitably wide grooves are great for old school vinyl DJs, and not just collectors. Eight of the songs are from the original 1977 compilation Philadelphia Classics (and have been masterfully remastered); the label has dug up another seven which have never been released before and commissioned an extra sixteen from Moulton himself, including ‘The Devil Made Me Do It’ by Robert Upchurch, ‘Jam Jam Jam All Night Long’ by People’s Choice, and ‘When Will I See You Again’ by The Three Degrees. Importantly it should be noted that the maestro’s key techniques don’t seem to have changed much over the years – and for this we should be thankful, I can’t think of any remixer who would benefit less from trying to keep with the times. (I’ve been laughing my ass off all week imagining various tracks with Fatboy Slim time stretching and ear boggling Skrillex bass drops.) In fact, apart from the tracks that I already knew about, I doubt I could have done a blind listening test on which were the new commissions and which were the unreleased tracks. (Although I’m pretty sure Mr Moulton has by now discovered the delights of working digitally instead of using razor and tape.)

But that’s the whole point, really: these aren’t remixes at all by today’s standards, they’re extended mixes, and Moulton is a master of extension. He just makes the whole process sound so damn organic. At no point during the colossal 11-minute version of Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes’ ‘Don’t Leave Me This Way’ are you thinking about scalpels and magnifying glasses and tape and glue – or chunks of WAV files, cut and pasted in Sony Acid Pro; this is "merely" soulful, classy Philly disco heard in its optimum form – the music sounds angelic and doesn’t make you think of process. These fuller, newer versions, in short, sound like the true originals. (Trainspotters will, doubtless enjoy poring over these mixes looking for what has been rebooted – ‘Don’t Leave Me This Way’ is probably constructed from extra recording session tapes or previously unheard versions, as it has a different, straighter four-to-the-floor disco drumbeat compared to the congas and funkier drumming on the 7". It also has some beautifully heartbroken ad libs by Teddy Pendergrass that I don’t recognise.)

Even when utilizing another one of his innovations – the disco breakdown – it never feels like he is cutting and pasting merely for the sake of creating long spacious grooves. His attention to detail and feel for subtle shifts in emphasis mean these long cuts never drag. Extension isn’t always an end in and of itself – the breakdown moves these songs further away from the radio station and nearer to the heart of the dancefloor. Elements which are fine for classic soulful pop in the context of a radio singalong or concert hall, such as downward modulated key changes or ornamental bridges, get chopped out and replaced by dramatic drops, where the elements of drums, percussion, bass, horn stabs, backing vocals and ad libs are reintroduced slowly – element by element, building to an ecstatic release and one last push to the end of the track. Sure, these breakdowns are long and spacious, but most dancers remain blissfully unaware of the absence of the key change or the slightly stiff musical arrangement they’re used to hearing on the radio – or any other feature that might distract from them getting lost in music.

This box set was originally released as a four CD set last year, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the label, and it feels like a timely collection of music. With emphasis over the last ten years in the world of disco reissues having been focused on slightly smoother and deeper sounds, then obscure re-edits, and even more recently on cosmic and international disco, it’s good to have such a great collection of classic Philly material out. While it’s obviously superb to get your hands on various bits of music by Tantra, Menergy and Chaplin Band – material which would have been rarer than hen’s teeth a decade ago – without this kind of bedrock classic disco in your life, they’re almost meaningless.

There are, naturally, a few songs here that I’ve never liked, such as ‘When Will I See You Again’ by The Three Degrees, and this compilation isn’t going to change that one iota. But by the same token the Tom Moulton remix of ‘Trammps Disco Theme/Zing Went The Strings’ is simply much better – and genuinely essential – than most of the weird beard, Balearic collector, blog hyped, cosmic disco rarities you care to mention. And elsewhere on this box I’ve heard tracks (‘Love Train’ by The O’Jays being a point in case) with fresh ears and realised their true brilliance for the first time.

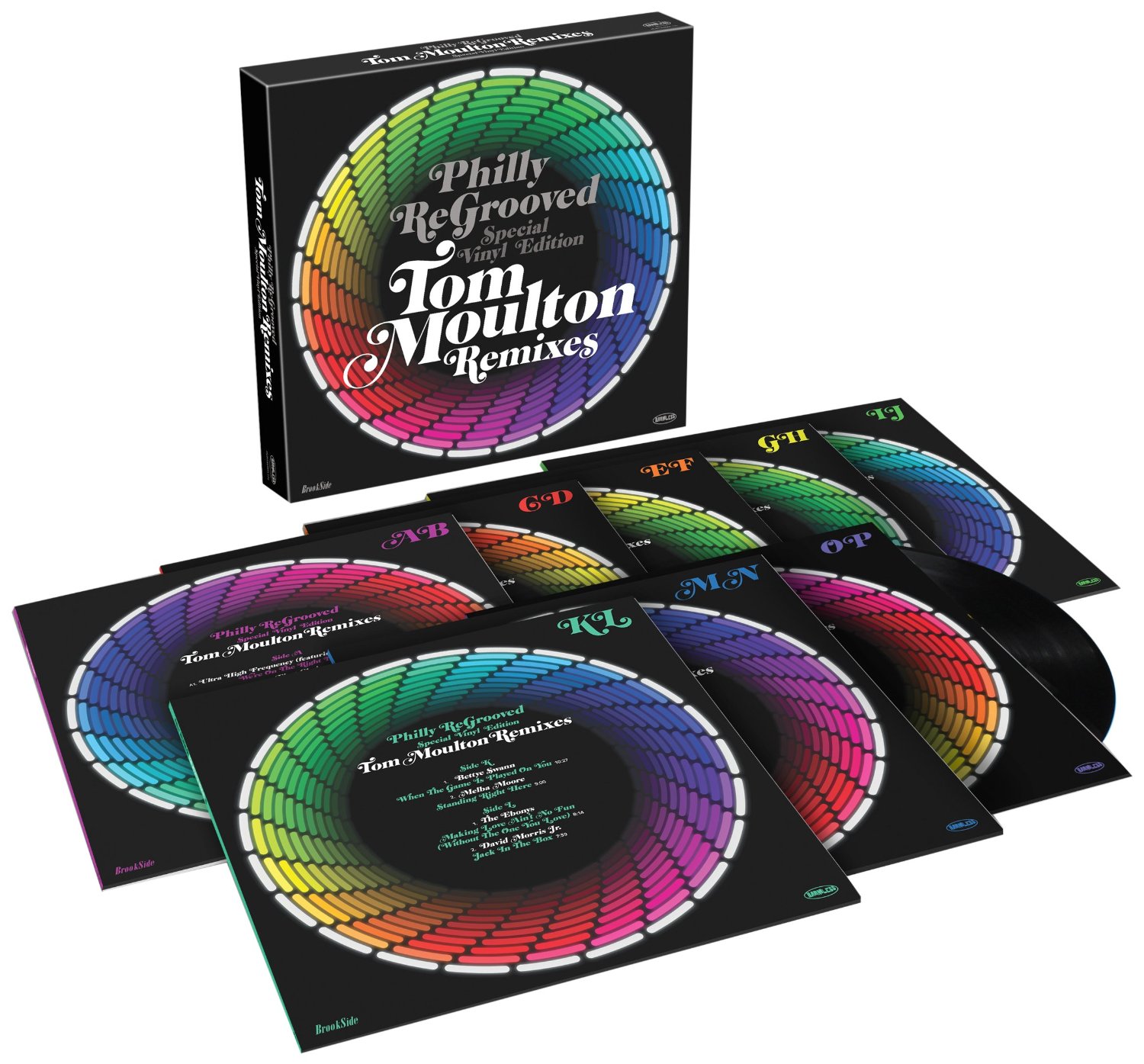

You wait forty years for one vinyl box set of extended Philly disco classics that weighs more than a breezeblock to arrive, and then two turn up at once. Philly Regrooved: Tom Moulton Remixes – Special Vinyl Edition is a slightly more off-the-beaten-track affair, with 40 tracks from the Philly Groove label spread over eight 12" records. (This is a compilation of the three Philly Regrooved CDs which you may have seen in shops since 2011 – the first one commissioned to celebrate the label’s 100th release.)

I’m no expert and I have no way of digitally analysing the waveforms that these remixes create when played on my turntable at home, but the tracks here occasionally feel like they may have been mastered too loud. Something of a common complaint in modern music, you might say, but perhaps not something you’d expect to be sometimes audibly noticeable on a disco reissue.

Also, it may sound like a modern complaint to claim that Moulton was guilty of helping making a black sound more ‘palatable’ for a white audience by emphasising the strings and tuneful production, but he did actually have this accusation levelled at him at the time. I’m not sure if it’s fair to claim this is exactly what he was doing, but certainly in very broad terms the Philly sound was more mainstream and less raw than that of disco from, say, New York – and out of the two box sets, this one is geared more towards the orchestral disco sound, with all the trappings of vibes, percussion, grand pianos, harps, multiple backing singers and a highly polished gloss sheen, so even though these acts (First Choice, The Spinners, Ultra High Frequency, Loose Change…) are mainly less well known, this is the box with a much more generic disco sound. However, this isn’t to say there aren’t stone cold classics here. Moulton’s languid reworking of William De Vaughn’s ‘Be Thankful For What You’ve Got’ takes an already brilliant track and just makes it ridiculously smooth and enjoyable.

But even when you’re listening to Bettye Swann’s ‘Kiss My Love Goodbye’, the ever so slight crunchy distortion to the metal on the drum kit and the clipping of the strings when they’re captured in full flight, mean that it’s probably always going to be at the back of your head that someone messed up the mastering of these tracks. Not the fault of the people who did the vinyl box for sure, but still, if your budget only allows you to buy one amazing package of disco reissues on vinyl this month (or year), make it Philadelphia International Classics: The Tom Moulton Remixes. It’s the clear winner.