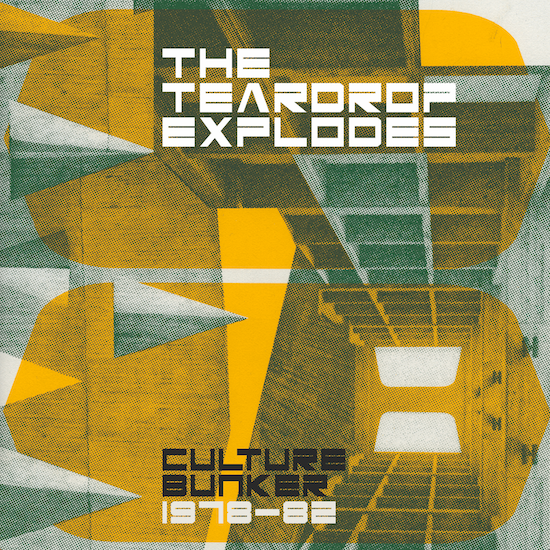

“While I’d long been loud about how much I hated pop stardom, the wider truth is I was no good at it,” wrote Julian Cope in his introduction to 2022’s CD-booklet commemorating his 1984 solo album, World Shut Your Mouth. Cope also talks of the fractious demise of his group, The Teardrop Explodes, who he calls “very good at best.” Yet here we are, with a massive six CD retrospective of the Teardrops, replete with lots of rarities, unreleased demos and live material about to be released. The group’s publicist Mick Houghton also goes in to bat for this inspiring and shapeshifting group with a sensitive essay in a richly illustrated booklet. Whether Cope was playfully casting the first stone with his recent remarks is guesswork on my part, but it fits the waspish narrative we’ve become accustomed to over the years. Regardless, the music – and you get an awful lot of their oeuvre here bar Peel Sessions and some of 2004’s Zoology – is thrilling.

When reading up about The Teardrop Explodes, with all the subplots, scene shifts and personal intrigue, it sometimes feels like trying to piece together a coherent narrative about an early Anglo-Saxon kingdom. New manuscripts turn up, old ones get reappraised over time. The cultural fall out from those who set forth from the Eric’s scene to conquer the British pop charts never seems to end: currently there is a film about the club in the pipeline, as well as a book from original member of the Teardrops and The Wild Swans, Paul Simpson. I’m sure that these new iterations of the legend will draw on plenty of new material, long lain mouldering in a shoe box in L8, to chew on and to add to the information in tomes like Cope’s magnificent account of the period, Head On, Bill Drummond’s 45, Will Sergeant’s Bunnyman or Houghton’s own recent memoirs. Typically Liverpool, you could say, a never ending source of language, dream, music, wit, poetry, snarky puns, true genius and endless tea and talking – often all at once.

Thinking mythologically and in retrospect, it feels that the group signing to Mercury is too perfect an act. Amongst other things, Mercury is the god of eloquence, communication and divination, luck, trickery and thieves; as well as the guide of souls to the underworld. All of these attributes could serve as a metaphor for some of the episodes in the short, tumultuous life of The Teardrop Explodes. It’s notable that the Teardrops go through (I think) eight lineup changes in four years with eleven band members; most hedonists and some devout Christians, as well as a supporting cast of acid-fried music biz chancers. Just Cope and the heart and soul of the band, drummer Gary Dwyer, are the constants.

After three years of dealing with bouts of rejection and adulation, it all gets too much: during December 1981’s Club Zoo residency in Liverpool (a run of gigs that morphs into the creation of a personal Court of Versailles) Sun King Cope renames the group Whopper, himself, Kevin Stapleton and some remaining members Milk, Old, and Buff Manilla. By late 1982, after opening for rock dinosaurs Queen to pay off debts, and a disastrous last tour where the band can’t play along to their own pre-programmed songs, this “Lunatic Visionary Acid Gobbler”, with a huge black cross magic-markered on his torso, chooses to saddle himself with the Teardrops’ entire debt. It surely makes sense that a lot of Teardrop songs mention things flying away or falling down around Cope, or him encountering different senses of self; a myriad of shifting situations and personalities.

But the more these tales, and the resulting songs of struggle and skin-changing settle in your mind, the more a sense of Cope’s personal battle to be the singer in his group becomes apparent: that of a man who was told he couldn’t sing, or looked too naff to be a frontman, or seen as too tense, an idiot or a dictator, or a teenage pinup, or whey-faced loon; to quote an old Teardrops press release. Someone whose ideas were seemingly used for other bands by his label and management and whose recordings were not seen as good enough for release or getting a deal. Or, even when he did get the breaks he still couldn’t play ball.

And yet, the brio and emotional promise of their music is their saving grace – and the reason people still talk about Teardrop Explodes with affection and respect. The songs often have an irresistible charm and frankness. Despite the wordplay and double meanings – as with ‘Culture Bunker’, ‘You Disappear From View’ or ‘Bent Out Of Shape’ – it’s very rare that the group indulge in the postmodern abstraction and atmospherics of the post punk era. It’s only at the end, with the unsingable third album, when the sound of that fractious decade starts to push its nose in. The magnificent and weird black sheep that is ‘Strange House In The Snow’ also stands out as a track that feels very 1980s. Otherwise it’s no stretch to say many, like the brilliant ‘Use Me’ or ‘Tiny Children’ sound like timeless pop and remarkably current. The directness of these songs, and their mix of vulnerability and confidence is always disarming: the single ‘Treason’, still one of Copey’s greatest songs in my books, can still make the heart skip a beat. And ‘Traison’ (the French version of ‘Treason’), shows how durable and adaptable his songwriting is; it’s not too much of a call to think it could have been written with French lyrics to begin with.

The early Zoo tracks are upbeat, tough, interesting, sometimes glorious. They are built like the most basic cars, easily maintainable and modifiable and there to keep running, regardless. And it’s a pleasant enough pastime to follow a song like ‘Sleeping Gas’ through the charming and spindly Zoo version via the slick, psyched take on Kilimanjaro to the deranged live Club Zoo take recorded on 22 December 1981. If only we could be transported back to this gloomy, ex-Liverpool Beat club and witness the “face solo” Copey indulges in on the latter.

Despite Dave Balfe being traditionally cast as Cope’s main creative sparring partner, the influence of the mystic Alan Gill really stands out as a vital influence in retrospect. It’s instructive to listen to the Cargo sessions and what became the final version of Kilimanjaro. Or contrast the YMCA gig from 1980 and the 1979 gigs. Would we be talking of The Teardrop Explodes’ music in the same way without him, especially when we consider his “gift” of their most famous song, ‘Reward’? I think not.

Many will make a beeline for the Club Zoo CD, but surely the treasure is found on CD four, The Great Dominions, where the songs that became Wilder are documented. Wilder is a magnificent and very singular record that still intrigues as the years pass, and here the early versions often more than hold their own against those on the official release. The Death Rattle CD is worth a good listen too, especially for those who don’t have the Shores Of Lake Placid on vinyl or Zoology. There are some fascinating takes of tracks from the 1990 LP release of their third, “lost” record, ‘Everybody Wants to Shag The Teardrop Explodes’, too, which still sounds bewitchingly strange.

The group always borrowed things: some are obvious here, such as the John Cale cover ‘I’m Not The Loving Kind’. Others require a bit of sleuthing and a knowledge of Cope’s musical interests: the synths on ‘Butcher’s Tale’ bring the opening track from Moebius and Plank’s Rastakrautpasta to mind. (Or maybe it was Balfey copping Talking Heads’ keyboard sound.) It’s also noticeable how much of Cope’s muse remains constant over time; we become aware that Cope doesn’t seem to let ideas go, rather they haunt him into reimagining snippets into new tracks. His assertion in his autobiography Repossessed, that he was a “songer”, concerned with documenting his feelings through his music, holds some credence with these tracks. The dedicated Cope and Teardrops fan will hear many echoes of many other songs, whether embodied in a lick, a turn of phrase or arrangement. The Great Dominions CD live version of ‘Colours Fly Away’ reminds me of ‘Girl Call’ on 20 Mothers. Fourteen years separate the two: all part of the creative process… With ‘Dialogue Between (Window Shopping)’ there are distinct psychic links between some of the dialogues heard on Jehovahkill and Peggy Suicide. The Great Dominions’ version of ‘Bent Out Of Shape’ brings ‘Head Hung Low’ to mind.

I’m sure other listeners will spot more. And then there’s a glorious, long-lost work out of what would later become ‘World Shut Your Mouth’ apparently recorded in 1981. Even in its embryonic state a sugar-candy pop song of some genius. Surely this release is the last chapter in the remarkable story of The Teardrop Explodes?

Culture Bunker 1978-82 is out today on UMR/EMI