The word “disruption” has become synonymous with rapacious technocrats destroying imperfect industries to ‘remake’ them so they preferentially remunerate said technocrats. Almost 70 years earlier, however, the disruption was coming from the other side. You don’t have to lean too romantic to see rock & roll’s shock-attack on culture as a key disruption in a disordered century. Rock & roll assaulted existing senses of taste and decorum, existing understandings of song form and acceptable sonic frequencies for entertainment purposes, existing segregational orthodoxies and unjust laws. Transgression incarnate, it was a visceral and conceptual thrill like no other. Like any controlled substance worth abusing, it left users endlessly grasping to re-experience that first high, that initial exposure, that original shock of the new, the unpredictable, the unknown. At the start of this century, few redelivered that shock as well as San Diegan quartet The Locust.

Their ornery, polymorphous cyclone of sound grabbed so freely from a smorgasbord of disagreeable noise that, by purpose and design, they were somewhat tricky to file. So let’s just call them ‘punk’, within a lineage of artists for whom disruption was much of the point. If punk was, essentially, a “return to Eden” movement seeking to repudiate the perceived cultural sins of the progressive movement, then it aimed to disrupt by paring rock & roll back to its primordial fundaments: to recapture the music’s ability to disorientate and disturb and electrify. But then, where next? Could punk progress and evolve without betraying its origins as a Year Zero cultural reboot, without conforming to cliché, without losing that visceral sense of shock?

You can hear this tension in an interview The Locust gave to San Diego TV show Fox Rox on Halloween of 2002, where bassist/vocalist Justin Pearson brushed aside the stereotype of “a fast drumbeat and some snotty kid with a mohawk and a guitar” to describe punk as “more like an ethical thing of where the band is coming from, socially, politically, economically”. The Locust sought not to adopt the uniform of punk rock, simply so they could operate within the paradigm. By the mid-90s, when they formed, that punk stereotype was beyond safe. The advent of grunge had proved that, while some adulterated version of punk was, briefly, widely saleable, compromising for the corporations ended with said corporations compromising your art, or perhaps simply not releasing it at all. Meanwhile, a wave of pop-punkers were going Platinum by pantomiming the ‘poooonk’ paradigm. Who could blame you for burning it all down?

The Locust were a disruption, alright: an unending and intentional shock to the senses, whose confrontational live shows were unforgettable. They sported homemade insectoid costumes and balaclavas, hewn from polyester and mesh, that made them look like unsettling primitive Doctor Who creatures. Their music was deranged, jackknifing in eight different directions at once, and then again, and then again. Their vinyl debut, one-half of a 1996 split 10” with powerviolence outfit Man Is The Bastard Noise, was like a field recording of uneasy Slayer acolytes jamming in the Black Hills of The Blair Witch Project, a found-footage symphony of abattoir sounds and torn throats and stop-start thrashing.

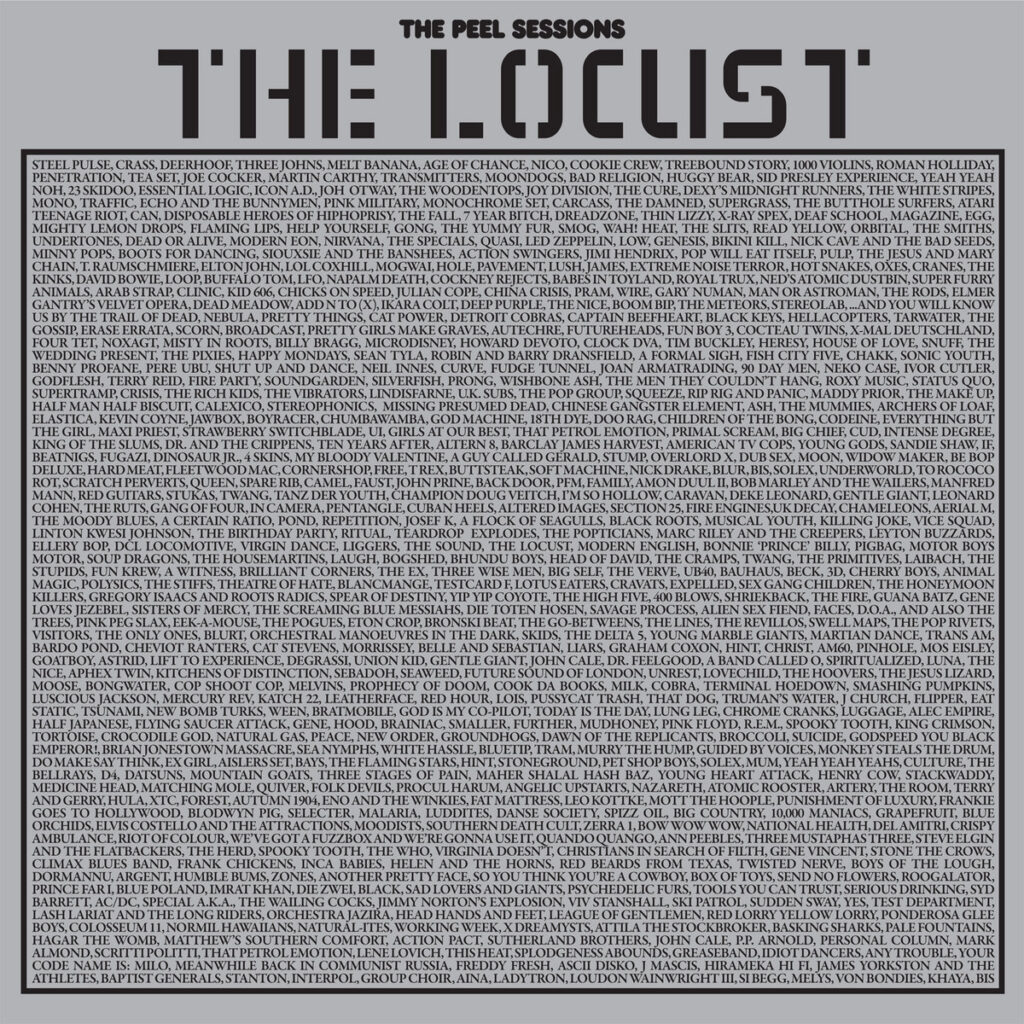

By the time they walked into the BBC’s Maida Vale studios to record their sole Peel Session, in August of 2001, The Locust had evolved a great deal. Their roots still lay in their local scene – among bands like Heroin, Antioch Arrow, Born Against and Clikatat Ikatowi – but they embraced bloody-minded electronic music, sharpening their sound with busted noo-wave synths that only accentuated the twisted, herky-jerky nature of their riffs. The vocals were serrated and piercing, inchoate screams. The songs were dead short – many seemed like they might be over by the time you’d read their lengthy titles – but went through many transitions and contortions over those precious seconds. The aggregated assault of all these elements, always changing form and attack, made them almost impossible to get a handle on, their violent left-turns impossible to predict. Their severity and invention, their unhinged ferocity, the discipline beneath that ferocity and the conceptual genius that guided every element – right down to those funky uniforms – were all the work of zero-sum gamers ready to scorch that earth back to the (hard)core, absolute end-of-history motherfuckers raring to scour your every sense red raw and leave you in a dazed sense of reckoning.

Recorded in late August of 2001, these 16 tracks (which pelt along in 13 or so minutes, for all you mathematicians out there) didn’t hit airwaves until 25 September, by which time the world looked entirely different from when the tapes had rolled. It’s hard to imagine how the uninitiated would have received this untrammelled vomit of noise that evening, though obviously dedicated Peel listeners would have been prepped somewhat by the DJ’s love for the likes of Atari Teenage Riot and all points further out. Perhaps the shock and awe of its rampaging from one sonic upset to the next made sense in that post-9/11, pre-Iraq War mess of uncertainty and simmering violence. The onslaught hit like an involuntary emission, with undigested slabs of reference surfacing every now and again – the paranoid pulse of The Doors’ ‘Not To Touch The Earth’ beneath ‘Stucco Obelisks Labeled As Trees’; ‘Wet Nurse Syndrome (Hand Me Down Display Case)’ echoing the helter skelter of Hüsker Dü’s ‘Reoccurring Dreams’; ‘Perils Of Believing In Round Squares’ slipping in and out of the existential slog of Black Flag’s ‘Damaged I’ – for listeners to grab hold of, before slipping away and stranding them amid a hailstorm of damaged electro-noise, last-gasp screaming and that kind of abrupt headsnap tempo-change that makes thrash-pits so much fun. Within the melee, Joey Karam’s organ sirens away like it’s soundtracking a murderous fairground ride, which in some ways it is.

The Peel Sessions captures The Locust mid-evolution, their vision better realised than on those embryonic split-singles, but perhaps less ambitious than later opuses like 2003’s deranging Plague Soundscapes or 2007’s ultimately valedictory New Erections. It’ll always be the apex The Locust emission for me, however, perfectly preserving, like a prehistoric bug in amber, the moment of disruption caused by first exposure. An avalanche of noise which never loses its ability to unnerve and thrill, and never becomes predictable, stretching that momentary sense that they’re a rollercoaster about to vacate its tracks across the entire quarter of an hour, wild synths wailing and voices tearing until the whole shebang slows to a crawl and then spins out again. It should be exhausting, enervating. Instead, it remains exhilarating, like Link Wray puncturing a speaker cabinet to make his guitar bark like a junkyard dog or Bad Brains revving punk rock to brutalised light speed, a perfect moment of rock & roll disruption that the passage of time cannot diminish.