As I approach Glasgow following a lengthy drive from Manchester, a sign highlights the turn off for the ‘City Centre’. Beneath it, a second placard announces, ‘Keep Your Distance’. It’s impossible to suppress a wry smile. I’m excited to be here again: despite the lazy ‘Glasgae Kiss’ clichés with which my soft, southern mentality is familiar, the reputation of the city’s romance precedes it, and I’ve always found myself charmed by its character. Seeing the sign again as I leave the city the next day, however, I realise that this time it was a prescient warning.

I’m here with a musician I’m tour managing, and we’re tired as we approach the end of a three-week European tour. I ferry her and our luggage to the hotel so she can rest before stowing the vehicle away in a nearby multi-storey car park

As I walk back to the hotel I hear shouts. A guy in a white tracksuit with green trim shoves me aside, pursued closely by two lads dressed in jeans and football colours. Seconds later, a young woman, dressed up to the nines for a night on the tiles, hobbles past on high heels. She’s screaming for the tracksuited man’s blood, and they catch up with him at the top of the street. Workers in a nearby kebab shop appear at their door to check what’s happening. They’re greeted by the sight of the tracksuited guy being knocked to the ground, kicked repeatedly in the head and stomach, and – whenever he tries to get up – tripped once more onto the pavement.

As this is going on, a smaller woman with a troubled complexion, a can of Special Brew spilling in her hand, wobbles towards them as fast as she can manage.

“Kill him!” she shrieks, waving her drink. “Fucking kill him! Kill him! Casual!”

She sounds delirious, drunk on adrenalin as much as the alcohol that has given her the appearance of a mid-fifties grandmother. To be honest, she may well be a mid-fifties grandmother, but her ruddy face suggests she has simply been pickled too long. I don’t want to get close enough to check.

Forced to follow the same route, I keep as quick a pace as I can towards my hotel without drawing attention to my presence. The streets are crowded enough for me to be far from the only witness, but no one else seems troubled. By now, the group has reached the main crossroads a hundred metres ahead where, to my horror, they send the guy sprawling into the path of an oncoming bus. The driver slams on the brakes – giving the victim enough time to pick himself up off the street and get out of the way – but then, unperturbed, carries on down the street. Meanwhile, the lad is again tripped over the moment he makes it to the pavement and booted in the head once more. I’m cowardly, I’m ashamed to admit, and keep my own head down for the last stretch back to my hotel. I’ve never been a hero, and this is not the place to audition.

Still troubled, I speak to the man behind the hotel reception desk.

“Is it normal to see guys getting their head kicked in round here?” I ask.

“Aye,” he says. “Happens.”

He turns away nonchalantly.

This is not the Glasgow I imagined when I fell in love with The Blue Nile. Give me a red car in the fountain any day you like, but a boot to the head? Where, I beg you, is the love?

I came to The Blue Nile far more easily, and with far fewer preconceptions, than to Glasgow. It was late 1989, and I was less than half a year out of boarding school, doing my best to enjoy work experience at a leading London advertising agency. I worked with a man called, in all seriousness, Dick Bush. Not content with having to suffer embarrassment alone, he’d christened his daughter Kate. Every day, a minute or two before 12.30pm, he’d slip quietly out of our office on the eleventh storey of a tall building next to what is now the British Library and take the lift to the fifth floor. Sometimes I’d descend with him, but we’d separate shortly afterwards as I headed towards the canteen for lunch and he made his way to the bar.

I was 18, but lunchtime drinking didn’t interest me terribly, and it wasn’t made any more attractive when he’d return to the office soon after 2pm, his breath acidic with the smell of white wine. I’d make him instant coffee and run errands for him before, an hour later, regular as clockwork, he’d throw down his pen and announce, “Fuck it. That’s enough.” Over two hours of working time remained before we could officially take our leave, but Dick didn’t care. When I left the company after my six months were up, I bought him a Zippo with his words engraved on the side. It wasn’t easy to get anyone to engrave something so vulgar onto a lighter, and I don’t think Dick realised how much effort I’d put into getting it done.

“I’ll have that written on my gravestone,” he observed concisely.

His lackadaisical attitude, fortunately, gave me a certain leeway on the days when I wanted to leave the building rather than eat at work. Dick’s timekeeping being somewhat awry, I could loiter a little longer than the hour’s break I was officially allocated, allowing me to venture a bit further than the W.H. Smiths in Kings Cross Station. It was a short tube ride to the twin palaces of Oxford Street’s HMV, where they let you listen to records on headphones spread around the store, and the Virgin Megastore, which stood on the gloomy corner of Tottenham Court Road close to a pub people told me to avoid since it was there that London’s paedophiles picked up young runaways. Once a week, normally the day after I’d devoured the latest issue of Melody Maker, I’d head to Oxford Circus and weigh up my options for my next purchase. I didn’t have much money: the job barely paid, and I still had to scrape together the cash to pay for the train ticket every day to and from Hampshire, where my parents lived, and I needed to save if I wanted to pursue my dreams of more adventurous journeys. But, nonetheless, I tended to risk expenditure at least once a fortnight, often based upon the inky reviews in the second half of the paper.

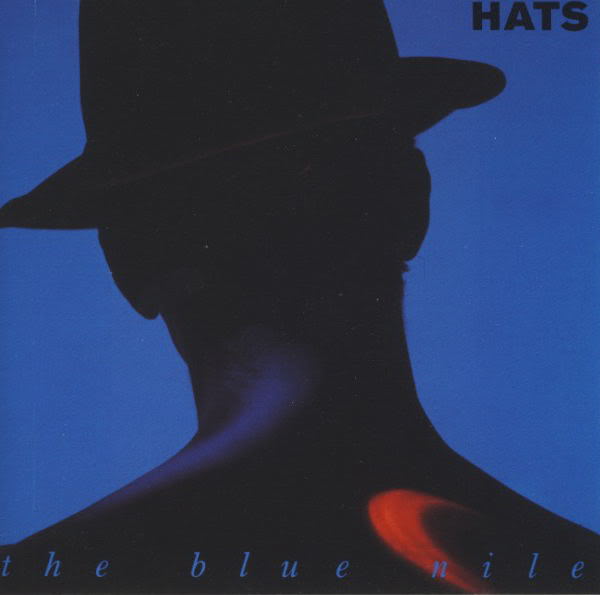

These shops were where I bought David Sylvian’s Secrets Of The Beehive, Neil Young’s Freedom, Spaceman 3’s Playing With Fire and The Sundays’ Reading, Writing And Arithmetic. Back then, I still had time to immerse myself entirely in records for hours on end, cassette spools turning until the batteries on my Walkman had died. I lived inside music, its universe a better, friendlier one than I saw around me, and knew every note, every word, every burst of feedback on almost every record I owned. But, of them all, The Blue Nile’s Hats became perhaps my biggest obsession, threatening to eclipse even my love for Talk Talk’s Spirit Of Eden.

At the time, I would probably have struggled to articulate my enthusiasm. “It’s just so beautiful,” might have been the limits of my explanation for its permanent rotation. But, looking back, the clue to its omnipresence in my life lies in the memory of my mother collecting me from the local station at the end of a working day not long after its release. Climbing into the car, I’d extracted the cassette from my personal stereo and asked if I could play it, a request to which my mother grudgingly acquiesced. Familiar with the less cultivated corners of my collection thanks to the sounds that bled under my bedroom door from the speakers in my room, she patiently indulged my passion for music, wishing only that I’d inherited her own for the likes of Chopin and Schubert. But The Blue Nile was something to which she couldn’t take exception, the reason being that it was, quite frankly, so unobjectionable.

I’d always responded to music in both an intellectual and emotional fashion, but this didn’t stop me from finding pleasure in sheer volume, rebellion and fury. Even the quieter music I enjoyed could be discordant or inexpertly played, and many of the voices provoked my mother to argue that, nowadays, people just can’t sing. But Hats was different. I found it dull at first, its drowsy pace and aseptic atmosphere lacking in prominent features. I’d signed a contract with it, however, when I’d handed over my money, and I fulfilled it by persevering until its alchemy was revealed. And what I discovered was in contrast to almost everything I listened to at the time.

Hats was polite, restrained and gentle. It was full of space and peace. I could revel in its romance. It transported me to windswept, empty streets lit with neon reflected on puddled pavements, and seduced me less with its emotional punch than a soft, tender caress. It was also something about which I could rhapsodise and remain baffled by anyone’s failure to appreciate it. It represented my promotion from schoolboy to sophisticated adult, and I wanted everyone who would listen to appreciate that transformation.

As the eighties turned into the nineties, I was still listening to the record. Like most middle class, former public schoolboys in their ‘gap year’, I embarked upon a world trip, but whether I was in Bangkok – where, within one night, “the world’s your oyster”, Murray Head had promised – New York, New Orleans or New Zealand, Hats was never far from my day bag, company through endless Greyhound bus rides, on long-haul plane rides, in lonely cafés after my travelling companion and I fell out, and at night, when I increasingly began to miss friends and familiar places. In conjunction with A Walk Across The Rooftops, the album which had preceded Hats five years earlier and which I’d soon purchased and adored almost as much, Hats helped build a picture in my head of the city about which it spoke.

The Blue Nile – Paul Buchanan (vocals, guitars), Robert Bell (bass) and Paul Joseph Moore (keyboards) – were not an effusive band, and so their music remained uncoloured by explanations for its content expressed boldly in interviews. The vision of Glasgow they conjured up in my imagination was uncompromised, its cinematography a blend of nocturnal colours and bleak, grey dawns. It was a desperate world of solitary individuals, but one in which redemption remained a possibility, though only if you were lucky enough to find love, itself a force that had the potential to be even more destructive than unifying.

Over time I would discover, through talking to other people similarly enamoured, that my images of the city were shared. We imagined this mythical metropolis to be a microcosm of the world, full of beauty and hardship, strength and failure, magic and tragedy, the essences of each condensed to manageable, tempting portions. The Blue Nile’s Glasgow was somehow twinned with Joy Division’s Manchester, and though their music was poles apart, there was a crepuscular, cobbled road that ran between the Salford group’s epitaph, ‘Atmosphere’, and the Scottish band’s glittering synthpop. The Blue Nile’s Glasgow hid dark, dingy corners but boasted night-time skies filled with stars. Its cafés were furnished with ring-stained formica tables across which couples pledged their love. Its roofs sprouted chimneys belching smoke into the air, yet offered views into the infinite distance of a barren but beautiful landscape. It was, you could say, our Emerald City in the Land of Oz.

You could attribute this vision of Glasgow to the lyrics, which seemed seeped in its enchantment and intrigue, but closer examination showed that there weren’t large numbers of references to the city at all. In fact it was never named, and only one place could be specifically pinned down: Renfield St Stephens Church, whose bells had jangled when The Blue Nile first walked across the rooftops on the title track of their debut album. It was merely the belief that the band lived in Glasgow, rather than the details that surrounded this lone certainty, that insisted it was where their tiny, kitchen sink, Chandler-meets-Brontë dramas took place.

And, oh, what a city it was. On that title track alone, it was filled with enigmatic and evocative features: “flags caught on the fences”, “telephones that ring all night”, “quiet redstones” and “black and white horizons.” Minutes later, it had evolved into ‘Tinseltown In The Rain’, where “tall buildings reach up in vain”, where you could suddenly find “a red car in the fountain”, where “men and women” lived their lives, “caught up in this great rhythm”.

On Hats, matching themes were explored, the album’s opening lines – “Working night and day, I try to get ahead/ But I don’t get ahead this way” – recalling those men and women trying to scratch out a living. Elsewhere, there was yet more singular, conspicuous imagery, ‘From A Late Night Train’ depicting “the cigarettes, the magazines, all stacked up in the rain”, while ‘Saturday Night’ portrayed streets “so big and wide” along which the protagonist strolled to his appointment outside ‘The Cherry Light’ at “Quarter to five/ When the storefronts are closed in paradise”. I could see it all.

‘The Downtown Lights’, from Hats, rendered the fullest picture, one brimming with “The neons and the cigarettes/ Rented rooms and rented cars/ The crowded streets, the empty bars/ Chimney tops and trumpets/ The golden lights, the loving prayers/ The coloured shoes, the empty trains”. These arresting snapshots seemed to confirm everything else that I’d heard in their lyrics, but failed to deny that this was nevertheless a lonely city, one which was frequently unable to offer comfort: “In love we’re all the same/ We’re walking down an empty street“, Buchanan states sadly early on, and by the end he’s wailing, “I’m tired of crying on the stairs”.

Notably, much of the action – if one can call it such a thing – that takes place on The Blue Nile’s first two albums happens in the wee small hours, something indicated by the song titles on Hats, six of which refer unequivocally to night time. ‘Let’s Go Out Tonight’, ‘Seven A.M.’ and ‘Saturday Night’, for example, all represent opportunities for celebration, and yet each speaks simultaneously of potential solitude. But the Glasgow I conceived didn’t only exist after dark, and nor was it always forlorn. ‘Easter Parade’, for instance, described “Confetti (that) falls from every window/ Throwing hats up in the air/ A city perfect in every detail”, and there was a genuine beauty in the quasi post-war era landscape they made visible, one with “hallways and railways stations/ Radio across the morning air”, where “fences and tumbledown bridges surround and divide” (‘From Rags To Riches’).

There was, too, the ever-present chance of escape: ‘From Rags To Riches’ spoke of how “People are leaving the squalor/ They’re leaving the houses and fires/ And starting out/ We find the waiting country”, while ‘Over The Hillside’ offered “the ferry… to carry us away into the air”. On ‘Lets Go Out Tonight’ we were even reassured that, “I know a place/ Where everything’s alright”. The most reliable form of salvation, however, was love. It was something that could at times unsettle – “How do I know you feel it? How do I know it’s true?” (‘The Downtown Lights’); “It’s over now/ I know it’s over/ But I love you so” (‘From A Late Night Train’); “Each time I fall for you/ It hurts me a little bit more/ Than I want it to/ I don’t want it to” (‘Seven A.M.’). But, at other times, it filled the void that lies at the centre of our existence so much of the time: “I am in love, I am in love with a feeling” (‘From Rags To Riches’); “An ordinary girl can make the world alright” (‘Saturday Night’).

The Blue Nile’s world was a mesmeric mixture of monochrome shades and subdued tones, realistic but not real. It was like a movie, its set built upon a Hollywood hillside – it was too exotic for Pinewood Studios, after all – and designed by Edward Hopper for a film scripted by Larry McMurtry and directed by Tony Richardson. It was peopled by vividly drawn characters who suffered but survived, the distant promise of better times ahead edging them forwards. Their faces were lined, weather beaten but noble, their surroundings gritty but beguiling. It was a place I wanted to visit, a place I willed to exist, and it was scored by some of the most delicate, refined sounds I’d ever heard.

The true beauty of the music that The Blue Nile recorded for those first two albums was its simplicity. The old-fashioned environment and values that their lyrics appeared to represent were reflected in the slow, sentimental pace of their compositions, which told of a place before supersonic travel, before electric trains, before the hustle and bustle of late twentieth century life. The production of the fourteen songs that made up their first two records may in fact have been state of the art – their first album was even funded by a local hi-fi manufacturer, Linn Electronics – but it ensured their songs sounded so pure that they shone brilliantly, compensating for their muted colours. There are synths at the start of ‘Over The Hillside’ that seem to hover like fog over a Scottish moor. There are horns that echo in the distance of ‘From A Late Night Train’ as though they just can’t bear to leave. And there are guitars that come in after five minutes or so on ‘The Downtown Lights’ – and oh, how they made us wait for that moment of deliverance – that, even though they nowadays sound like the very definition of the glossy, late 1980s, back then seemed to shimmer like stars in the “wild, wild sky” mentioned in ‘From Rags To Riches’.

Within all of this, there was Paul Buchanan’s voice, a thing of quiet, relaxed beauty that radiated directly from his soul. It was suffused with a sad resignation, but still, like the characters in his songs, clung to optimism with heroic determination. It rarely rose much above a whisper, but it made the world seem a little less frightening, a little less desolate, just by confirming that a man like this – noble and patient – existed, persisted, and might identify with me as much as I identified with him. Even if that time wasn’t now, when my life seemed comparatively safe, I knew the day lay ahead, probably not so far away, when I would be older and forced to confront the adult dramas of which he sang, the setbacks and heartbreaks and tragedies that await us all.

A little less than four years after the release of Hats, after the release of a record whose beauty had endlessly haunted but consoled me, I found myself sitting atop a small hillside on Dartmoor with three friends from my university. It was our final night before we left Devon forever, and we’d decided to escape to the countryside with a six-pack to toast our future. It was an early night in July, but, as night drew in, we were suddenly enveloped by a thick, grey mist that reduced visibility to mere metres. It was impossible to see what lay ahead, and the car, only a short walk down into the valley, had disappeared, the ground so uneven that we lost our sense of direction.

As we stumbled forwards, we heard what sounded like the click of a rifle. We looked at one another, then around us. There was no one in sight. But, then, so close we could almost feel spit land on our faces, there was a voice.

“Halt! Who goes there?”

We froze. The command was repeated.

“We’re lost,” I replied timidly. “We’re students.”

We heard footsteps, and suddenly three soldiers loomed into view.

“What are you doing?” one of them demanded.

We were innocent but nervous. One of us had drugs and we knew that parts of the moor were out of bounds, so it wasn’t impossible that we’d strayed onto Military Of Defence territory. We tried to explain ourselves, but the soldiers were unsure as to whether our excuses were authentic or part of the exercise upon which they’d earlier embarked. At last convinced, they marched us efficiently out of the mist towards the road so that we could locate the car, then lectured us about safety. We were shaken: not only had we got lost as darkness fell on a bleak, barren wasteland, but we’d nearly been taken captive by squaddies with guns.

The situation called for The Blue Nile.

I started the car engine and switched on the stereo. As we wound along narrow roads, sitting in silence, we contemplated the lives we would soon commence now that we’d completed our education. “Working night and day/ I try to get ahead/ But I don’t get ahead this way”, Paul Buchanan sang gently, and then, as we fell into the darkest shadows of rocky outcrops, “Over the hillside/ Over the moment/ Over the hills and waiting”. I thought of the world the band inhabited and felt calmer, more at ease.

We drove on, my companions staring wordlessly out of the windows. There wasn’t anything to say. We passed fences and tumbledown bridges as we neared the edge of the moor, and the song slid slowly towards its conclusion, before the opening notes of the next track sparkled so brightly they illuminated the friends around me, their presence in turn lighting up the words we heard:

“Sometimes I walk away

When all I really wanna do

Is love and hold you right.

There is just one thing I can say:

Nobody loves you this way.”

And then, as we crested a peak, Buchanan was there for us again, the lights of a village that confirmed we were nearly back in civilisation glowing on the horizon, little towns soon rolling by:

“It’s alright.

Can’t you see

The downtown lights?”

Twelve years later I would see a man booted in the head on the streets of Glasgow, the city that The Blue Nile had built for me. But, by then, I’d learned that the Glasgow that The Blue Nile had constructed is a fantasy. It’s in their music, it’s in their poetry, and it’s in the minds of all of those who have lived inside their records. But most of all, it’s in my head.

“I am in love. I am in love with a feeling…”