‘London swings… it is the scene,’ declares TIME magazine’s 15 April 1966 cover story. The most ‘with it’ ‘fab’ ‘groovy’ ‘kinky’ place on earth. Hopping from boutique to art gallery to discotheque to restaurant, writer Piri Halasz observes a city where pop stars, actors, designers and toffs are all part of one classless ‘bloodless revolution.’

The world is watching. American country singer Roger Miller enjoys a transatlantic hit with ‘England Swings’ (‘like a pendulum do’). The kingpin of Euro arthouse cinema, Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni will film Blow Up in London – featuring The Yardbirds, a tight-trousered Jeff Beck smashing his Hofner guitar while sporting an erection.

Just over a week later, Guinness heir Tara Browne throws his 21st birthday party at the family seat, Luggala, in the Wicklow mountains – a gothic revival folly resembling an ice cream crown melting into the landscape. The nearby Lough Tay, pitch black and fringed with imported white sand looks like the family’s fortune. At Browne’s bash, The Lovin’ Spoonful play to a guest list that includes Mick Jagger, Brian Jones, Marianne Faithfull and Anita Pallenberg, as well as photographer Michael Cooper. He’ll shoot Browne and Jones for a Vogue fashion spread, wearing the kind of sartorial arcana sold at London boutiques Granny Takes A Trip, Lord Kitchener’s Valet and Beatle favourite Hung On You. Next year Cooper’s lens will capture the most famous LP cover of all time, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

John, Paul, George and Ringo are all absent – McCartney’s brother Mike is the nearest thing here to a Beatle, despite Browne’s friendship with Paul. Late last year Mike had been with Paul when he took his first LSD trip at Browne’s Eaton Row Belgravia home. That Christmas he’d also been there when the Beatle flew off his moped split his lip and chipped his tooth while visiting father McCartney in the Wirral.

The Beatles have been hard at work at EMI Recording Studios making their seventh album. Yesterday they finished a song variously known as ‘Mark 1’ and ‘The Void’, eventually called ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, inspired by the LSD that’s on the menu tonight at Luggala…

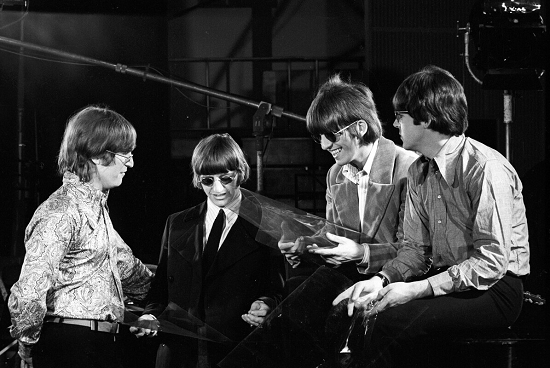

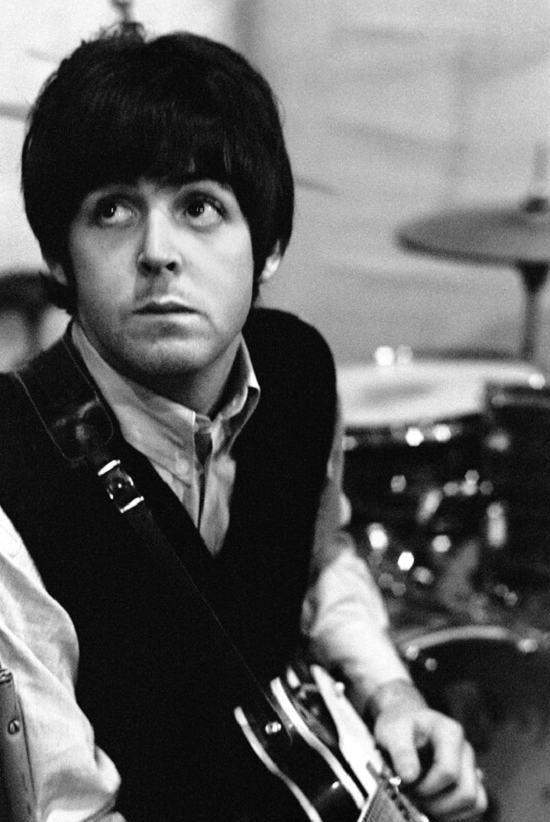

The Beatles in Abbey Road Studios, 19 May 1966. Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

By the end of 1965 The Beatles’ place at ‘the toppermost of the poppermost’ was intact. Rubber Soul and double A-side single ‘Day Tripper’/’We Can Work It Out’ were both transatlantic number ones. Both the establishment and the emerging counter-culture embraced them; MBEs had come in October and Rubber Soul was the soundtrack to the whole Haight-Ashbury/Berkeley scene. Their peers marvelled too – Brian Wilson didn’t sleep for two days after hearing it.

But the competition had been fierce, full of revved-up pop expanding its musical/emotional possibilities. The Yardbirds‘ harpsichord-festooned ‘For Your Love’ had sent Blues purist Clapton packing but seduced record-buyers. 45s with replacement Jeff beck saw him emulating a sitar on ‘Heart Full Of Soul’ while ‘Still I’m Sad’ featured Gregorian chants. India surfaced on ‘See My Friends’ too – a hypnotic, droning, possibly gay-themed Kinks single that McCartney played repeatedly. Those galvanized by The Beatles now posed a challenge. Not least The Stones, with number ones like ‘Satisfaction’’s fuzz-toned frenzy, and creative advances like ‘Play With Fire’, moving from blues to baroque. The Dave Clark Five had their own film, Catch Us If You Can and the US Christmas Number One with ‘Over and Over’.

In 1965 McCartney had two favourites. One was The Who, pushing pop to wild sonic extremes on ‘My Generation’ and ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere’. The other was Dylan. His influence rivalled The Beatles, ushering in a folk pop boom that veered from the sublime –Donovan’s ‘Catch The Wind’, to the more polarizing – Barry McGuire’s US Number One ‘Eve Of Destruction’. Pop intensity swelled to almost gothic proportions by December with The Supremes’ ‘My World Is Empty Without You’, another Black triumph in the year of Otis Blue and James Brown’s rise.

As 1966 begun and ‘We Can Work It Out’ jostled with Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘The Sound Of Silence’ for the US top spot, The Beatles took their longest break since 1962. After a nine-day December tour (their last in Britain) that climaxed with two riotous London dates, and with their next film temporarily shelved, they retreated. Lennon and Starr returned to suburban Weybridge.

Cocooned in the mock Tudor Kenwood, on top of a hill, Lennon was a mass of contradictions. Interviewed by Maureen Cleave in a London Evening Standard series through March 1966, that profiled each Beatle, he was described as the ‘laziest man in England’ but one who was forever ‘painting and taping and drawing and writing,’ publishing two books, illustrating Oxfam Christmas cards and reading voraciously. Surrounded by luxury he was still dissatisfied ‘This isn’t it for me,’ he told Cleave.

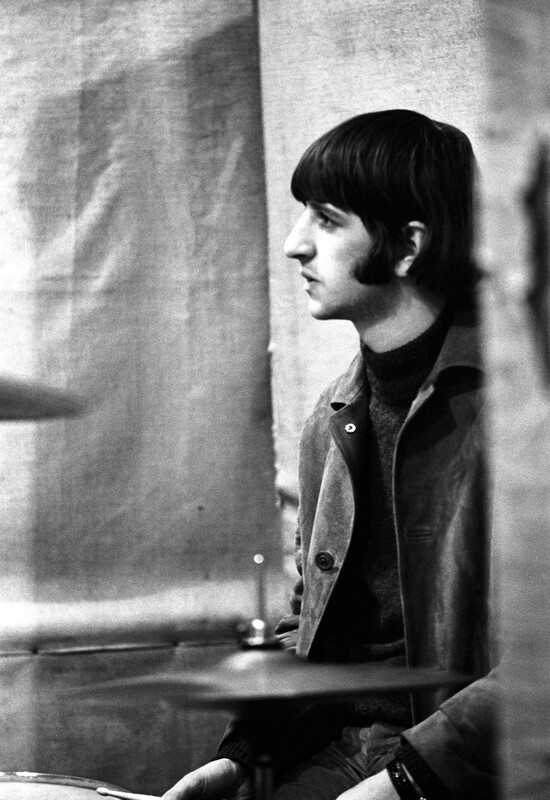

Ringo Starr in Abbey Road Studios, 1966. Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

Behind a tough façade and merciless cruel streak lay a sensitive soul nursing deep wounds. Lennon’s emotional and perceptual doors had been blown wide open by LSD. He’d been taking the drug since late March the previous year, when he and Harrison had been spiked at a Bayswater dinner party (the more cautious McCartney waited until December that year). Marijuana had already sharpened The Beatles’ sonic edge (see the underrated Beatles For Sale and ‘Ticket To Ride’). Traces of acid could be detected on Help! and Rubber Soul. On Revolver the drug would be central.

So would the Indian music Harrison had been delving into during his time off. He’d come across a sitar filming Help!; later, The Byrds had given him a Ravi Shankar album. He’d bought his own sitar at London’s Indiacraft adding it to Rubber Soul’s ‘Norwegian Wood’. He told Cleave the instrument had given him ‘a new meaning to life’. Seeing Shankar play live was equally revelatory, ’like everything you thought of as great coming out at once.’

Pop’s continuing flirtation with Indian music would produce stunning 45s in 1966, the Raga-meets-Coltrane of The Byrds’ ‘8 Miles High’ and the sitar driven ‘Paint It Black’. But with the craze came modish window-dressing (the kind satirized on Bowie’s ‘Join Our Gang’ the following year). ‘Love You To’, however, a work-in-progress Harrison played to Cleave, showed a total immersion in Hindustani Classical Music. Ecstatically spinning in life’s bigger, everlasting cycle, it was the radiant light to ‘Paint It Black’’s diabolical dark. Recorded later in April for Revolver, with student Anil Bhagwat, a Tabla player found via Indian performing arts centre, the Asian Music Circle, ‘Love You To’ was the pop distillation of Shankar’s epic ragas.

Harrison’s Indian style, which rapidly developed on ‘Within You Without You’ and ‘The Inner Light’, shaped The Beatles’ wider sound, influencing Lennon and McCartney’s experiments with mono-chordal composition, adding colour to the latter’s playing. Another of Harrison’s Revolver compositions, ‘I Want To Tell You’, with it’s strutting McCartney piano, shows how they elevated each other’s material.

In London McCartney was a tornado of creative energy, embarking upon a hyperactive self-education programme. Observant, fascinated, a bit nosy, McCartney collected art (Paolozzi, Blake, Magritte) & attended plays – absurdist Albert Jerry was a favourite; he’d been an investor in Joe Orton’s Loot. His ears pricked up to electronic and avant-garde music by Stockhausen and experimental free jazz outfit AMM, and he attended a Luciano Berio lecture at London’s Italian Institute (Musique concrète symphonies of clinking glasses and radio bleeps were an enthusiasm Lennon shared).

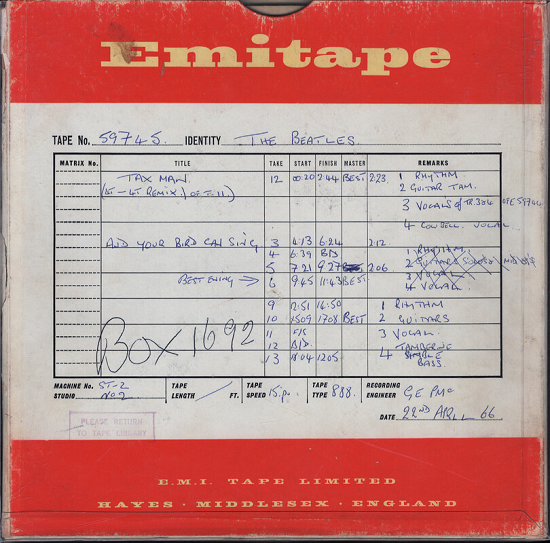

The original tape box for ‘Taxman’ and ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’ Courtesy of Calderstone Productions Ltd.

He became a regular visitor at the Indica Bookshop & Gallery when it opened in February 1966. Run by John Dunbar, who married Marianne Faithfull, and friend Barry Miles, Indica was a conduit for all things underground and experimental, situated a few doors from Beatles haunt The Scotch of St. James. Not only did McCartney help renovate the space, he designed wallpaper and rifled through its stock. Besides books on pacifism and drugs, were LPs on the ESP label, including free jazz (Albert Ayler) and the New York Underground (The Fugs).

Through Indica, McCartney met William S Burroughs, who remembers McCartney using Starr’s London base, 34 Montagu Square, as a small studio, working on ‘Eleanor Rigby’. Years before Bowie adopted Burroughs/Gysin cut-up techniques, McCartney, armed with Brenell tape machines, was making loops of sound, ‘cutting into the present with the future leaking out’, to paraphrase Burroughs. A lover of cinema and British TV drama, McCartney shot home movies with a Bolex camera, and showed them to Antonioni. ‘He sees no limits to his own possibilities… he would like to know everything,’ Cleave observed in the Evening Standard profile.

This frenzied forward thinking energy would be contained within The Beatles’ pop instincts on Revolver. Impeccably neat (the Beatle whose dirty shirt cuffs had unsettled him whilst tripping), McCartney expressed concern about going ‘too far out’ too quickly. Nevertheless, a photo session with Robert Whitaker on 25 March,, just before Revolver’s sessions began, hinted at The Beatles’ urge to challenge, even alienate their audience. Dressed in white coats, they’re draped in slabs of bloody red meat and dismembered dolls, in an image later branded ‘sick’ by Disc And Music Echo readers when it advertised the ‘Paperback Writer’ single; it also got initial pressings of US compilation Yesterday And Today withdrawn by Capitol. Revolver was going to be ‘very different’.

Producer George Martin happily co-piloted the experimental transformation, with a CV that already include tape loops (Ray Cathode’s 1962 ‘Time Beat’), ethno-pop (Rolf Harris’ ‘Sun Arise’) and children’s sing-a-longs (Mandy Miller’s ‘Nellie The Elephant’), as well as classical recordings. New engineer Geoff Emerick was also invaluable. Just 20 years old, he’d been a tape-op on ‘Sun Arise’ and several Beatles sessions, engineered Manfred Mann’s ‘Pretty Flamingo’ and providing radio plays with musique concrète -style backdrops.

Abbey Road (then EMI Recording Studios), still operated under strict guidelines enforced by bespectacled white coats, anxiously observing meters going into the red for distortion levels. Revolver’s team would break rules – microphones were placed perilously close to bass drums, stuck inside the bells of brass instruments, even wrapped in polythene bags and placed in water. This was an ’in your face’ sound taking you right ‘there’, as 1966 as Michael Caine breaking the fourth wall to address the viewer in Alfie. Within the constraints of four-track recording, they devised techniques and supplied gadgetry that would help The Beatles achieve their vision.

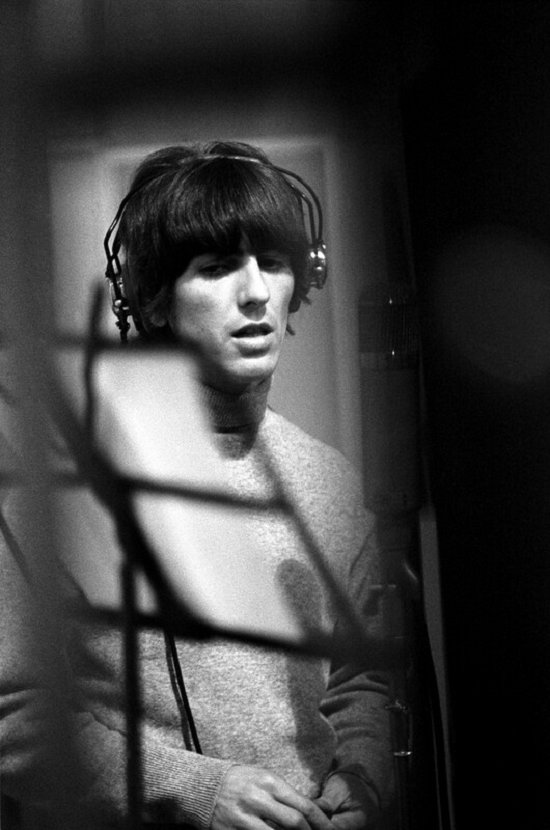

George Harrison in Abbey Road Studios, 1966. Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

Technical engineer Ken Townsend was vital, his artificial double tracking instantly created a replica of an instrument or voice, milliseconds out of sync, producing a dreamy, thickening effect (‘a cousin not a clone’). Fairchild Limiters were integral too, compressing Lennon’s voice and Starr’s drums. To get the hefty bass boost The Beatles hankered for, Studio Two’s huge ‘white elephant’ speakers were rewired into a vast microphone for ‘Paperback Writer’, while the risk of stylus hopping on low-grade record players was minimized through the ATOC (Automatic Transient Overload Control) cutting technique. Revolver was the product of an entire team working to a fiercely creative degree – an innovation of ‘togetherness’ that echoed the Beatles’ internal dynamics during this period.

They entered the studio on April 6 at around 8pm to record Tomorrow Never Knows’ (then ‘The Void’ or ‘Mark One’). Many of it’s lyrics, including the opening lines, quote The Psychedelic Experience, a 1964 manual by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert, repurposing a translation of The Tibetan Book Of The Dead for LSD users. For the vocal, Lennon wanted a ‘Dalai Lama chanting on a hilltop’ effect. Martin and Emerick responded by sending his voice through a Hammond organ’s Leslie cabinet transforming it into something otherworldly, swirling, psychedelic.

The first day’s backing track was startling enough – Starr playing to a throbbing ‘underwater’ tape loop – the next day, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was whipped into shape. Starr provided a new walloping broken beat, tape machines were scattered across the studio complex, technicians at the ready with pencils for improvised spools, feeding loops into the console, controlled with the faders. These loops featured an orchestral chord, a sitar, mellotron strings and flutes, and a gull-like McCartney laughing, sped up and reversed. By 22 April Revolver’s first masterpiece was complete, with tanpura drones, backwards-sounding guitar and a Goons-style Wild West saloon piano outro.

It captured LSD’s synaesthetic sensations perfectly – a kaleidoscopic light display of sound, a shimmering, spinning ‘chaos of dancing energies’ to borrow Ian Macdonald’s description of the 1960s. Early reactions were extreme: ‘hypnotically horrifying‘ said Record Mirror’s Tony Hall. Cilla Black laughed.

Concerned speculation around LSD intensified as Revolver took shape – Transatlantic panic-stricken media coverage paving the way for the drug’s eventual criminalisation. But the charts were already so drug-addled, from The Association’s ‘Along Comes Mary’ to the acid-fuelled ‘Eight Miles High’, that there’d been a rebuttal from Paul Revere And The Raiders, ‘Kicks’, warning of the dangers of a ‘magic carpet ride’. The same month ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was recorded, The Dovers issued ‘The Third Eye’, another terrifyingly sublime evocation of LSD. Something lysergic was seeping into Hollywood too. Stanley Donen’s Arabesque had hallucinogenic optical effects for its opening sequence, and Gregory Peck ‘tripping’ on a truth serum. In the pages of Thomas Pynchon’s Crying Of Lot 49, LSD and Beatles references came close together.

Recorded a year before Pink Floyd released ‘Arnold Layne’, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was a flash into the future: electronic, looped, danceable (‘will be popular in discotheques,’ noted Ray Davies), an inspiration to everyone from Cosey Fanni Tutti to The Chemical Brothers. There were others – The Velvets similarly droning ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ arrived that summer, that August, Delia Derbyshire secretly invented synth pop with Anthony Newley on the unreleased ‘Moogies Bloogies’.

The Beatles in Abbey Road Studios, 19 May 1966. Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

According to Lennon, Revolver’s second recording, McCartney’s ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’ was about acid (its writer said pot). Regardless, Stax and Tamla loom large here, part of a mutual appreciation with Black American music that would later see Earth, Wind & Fire take this into the US top 10. There’d been talks of a Beatles/Motown collaboration, sessions for Revolver had originally been scheduled at Stax (Rubber Soul out-take 12 Bar Original was a homage to the studio’s house band, Booker T And The M.G.’s). Neither materialized.

It evolved throughout the album’s making, an organ part being replaced by a double-tracked horn quartet, consisting of members of Georgie Fame’s The Blue Flames. Big and brassy, like the Martin-produced ‘Goldfinger’ or Laurie Johnson’s Avengers theme, the compressed sound points forward to ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’, ‘Savoy Truffle’, even Dexy’s. It’s also a vocal showcase, McCartney switching from jazzy, doe-eyed romance to full-throttle blues holler (hear his swaggering shadowing of Lennon elsewhere on ‘Dr. Robert’). Superimposed, overdubbed guitars bring revved-up super-focus, as if higher voltage electricity’s coursing through it, as if the acid’s kicking in. The outro is frenzied.

Similarly turbo-charged was standalone single ‘Paperback Writer’, released 10 June and cut after Harrison’s ‘Love You To’. The bass is boosted, the guitars distorted while Starr unleashes frantic rolls. A stop-start dynamic, with tape delays and echo on the acapella breakdown, enhances the druggy delirium. Written around a single chord, Beach Boys-style four-part harmonies add polyphonic complexity. Like the words, they’re tongue in cheek, singing Frere Jacques.

Inspired possibly by a Daily Mail story, it’s written as a letter from an aspiring writer to a publisher that becomes increasingly surreal. The paperback, a ‘dirty story’ (‘The Miller’s Tale’ ignited McCartney’s boyhood imagination), bloats to 1,000 pages, there are books within books, literary master of nonsense Edward Lear gets a nod. The author’s naked ambition is gently mocked, twisted and everywhere, sent through a hall of mirrors, via all those harmonies and that echo. It’s a healthily sceptical northern eye-roll perhaps at the whole swinging set, a cuddly cousin to Ray Davies’ ever-sharpening satire.

Its flipside, Lennon’s ‘Rain’, was for critic Ian MacDonald about ‘the vibrant lucidity of a benign LSD experience’. For McCartney it was about the joy of letting ‘the rain drip down your back’, reflected in his sensual, fluid bass runs. Saturated in studio artifice, it’s a symphony of altered states, the backing track slowed down making Starr’s ‘possessed’ drumming deep and heavy, the vocal sped up. Textures collide – clanging guitars meet waves of eastern-sounding harmonies, the unease/ bliss of acid’s perceptual tsunami.

The masterstroke coda, a tape of Lennon singing spooled backwards, was either a Martin brainwave or stumbled upon by Lennon at home, joint in hand, mistakenly playing a reversed rough mix on his reel to reel. The line between those who embraced the downpour and the ones running for cover was clearly the one separating those who ingested LSD and those who didn’t –a division Lennon saw clearly as he gobbled acid in Weybridge, surrounded by stockbrokers and bankers. By the end of 1966 Small Faces’ ‘My Mind’s Eye’ was carrying a very similar message.

Much of this was echoed on Revolver’s ‘I’m Only Sleeping’, Lennon woozily luxuriating in his indolence, ‘floating upstream’ while crazy fools rush around him. It’s another narcotic reverie, with vari-speed vocals (‘bright and thin like an old man’) and an enveloping sound design, featuring backwards guitar (Harrison’s raga-like runs). Here was the lazy loafer not as the effete, fading aristocrat of The Kinks’ ‘Sunny Afternoon’ but enlightened seer. Its recording followed two more Lennon songs. ‘Dr. Robert’ was a razor-sharp vignette, possibly inspired by German born Freymann, an Upper East Side doctor who administered vitamin B-12 shots laced with methedrine to Manhattan socialites. ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’, was a rush of Byrdsy guitars, Lennon/McCartney’s voices ecstatically entwined.

Recorded before ‘I’m Only Sleeping’ was ‘Taxman’ by Harrison (the ‘quiet one’ with the forceful views), a sardonic swipe at Wilson’s tax code – 19 shillings and 6p to the pound. Taxmen also populated ‘Sunny Afternoon’ and Yardbirds’ ‘I Can’t Make Your Way’. It’s unfair to see Taxman through our current tax-dodging prism, however – this was 1966, where working class achievement in a fickle, cut-throat industry was being penalized. To Questlove in the text accompanying the new reissue it’s a defiant rejection of state control like ‘Fuck Tha Police’.

Musical inspiration came from Harrison’s Black America-dominated jukebox – though the way he plays the titular villain with his ‘sexy’ (Ray Davies) double-tracked vocals emphasized similarities with the theme from America’s camp new TV show, Batman. Opening Revolver with McCartney’s slurred count-in, it locks into a tight, tense groove that’s swiftly spun into a kaleidoscope – back-up vocals harmonize then shout-out to Wilson and the opposition’s Ted Heath, an echoing cowbell rattles like siphoned coins. Release comes with McCartney’s frenetic Epiphone Casino guitar solo – so good it’s repeated, bolted onto the outro, foreshadowing both cut/paste pop methods and the emerging ‘heavy’ rock style.

McCartney had been working on ‘Eleanor Rigby’ since late 1965. Initially called ‘Daisy Hawkins’, the title change came from Help! star Eleanor Bron, and a wine merchant, Rigby & Evens Ltd, he spotted in Bristol, visiting Asher performing at the Theatre Royal. A gravestone bearing the song’s namesake lay in the same Woolton St. Peter’s Church, where McCartney met Lennon in 1957. Pure coincidence perhaps, but the song is rooted in Liverpool where the young McCartney would be regaled with tales by lonely old women. Writer AS Byatt praised it for having ‘the compression of a Beckett story’. It’s an astonishing piece of poetic pop story-telling, with all McCartney’s current enthusiasms squeezed into 126 seconds; he moves through them like the roving eye of a movie camera.

It’s brim-full of detail. That ‘face in the jar’ may have come from Mother McCartney’s love of Nivea cold cream, but here it’s a sad, sinister, surreal prop, a mask worn to hide from the outside world. Amid the unflinching despair, little lines offer cute relief – Father Mackenzie darning his sock, apparently Starr’s contribution. Others hint at the richer interior of dreary lives. Like T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock, like Billy Liar, Rigby ‘lives in a dream’. It’s ‘Richard Cory’ in reverse, Simon and Garfunkel’s tale of an envied factory owning socialite who blows his brains out (Wings covered it later). The narrative carries subversion – organized religion has failed, unable to bring these two together in life, a far subtler critique than Lennon’s ‘more popular than Jesus’ remarks. Old age, death and loneliness had rarely been tackled with such unsentimental empathy in pop before. ‘Youth is the word in London,’ said TIME’s April feature; ‘Eleanor Rigby’ showed compassion for lives that weren’t swinging.

Paul McCartney in Abbey Road Studios, 1966 Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

It broke conventions musically too with its stark backing. Even before the vocals were added, the Martin arrangement for string octet told the story. Brisk, rhythmic, severe passages, they give way to a sighing, dying sweep; the urgency of a lonely life running out of time (Martin cited Herrmann’s Psycho as inspiration, while McCartney had recently been introduced to Vivaldi by the Ashers). Covered by Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin, ‘Eleanor Rigby’ would be a major contribution to the evolving baroque style – classically tinged, lavishly orchestrated pop that travelled back and forth across the Atlantic. Unlike Pet Sounds, though, it was neither lush nor romantic but a highly original use of strings echoed by Simon And Garfunkel’s ‘Old Friends’, Nico’s ‘No One Is There’, Mandy More’s extraordinary ‘Alone In My Yellow’ and Kate Bush’s work on The Dreaming and Hounds Of Love (she devised a routine to the song as a child).

Beginning life in a Swiss chalet bathroom, while McCartney holidayed with Asher in March 1966, ‘For No One’ was more restrained baroque. Originally titled Why Did It Die? it’s dominated by piano, clavichord and a French horn played by Alan Civil, who joined the BBC Symphony Orchestra that year (integral to pop’s expanding palette in 1966, the ‘Session Man’ even got a Kinks song). Observing a break-up from the third person, there’s the same marriage of lyrical and musical economy as ‘Eleanor Rigby’, the same cold eye/warm heart of a good dramatist. It’s elegant but far less grandiose than that year’s other great baroque break-up song, Simon And Garfunkel’s ‘The Dangling Conversation’.

Often seen as ‘soppy’ (his words), here McCartney’s tapping into the same northern realism that shaped British New Wave cinema and spawned the Smiths decades later. Cilla Black’s cover lacked the original’s modern bite, making the spurned lover female. It was, after all, a year when women were dumping men at 45 rpm – The Shangri-Las’ ‘He Cried’, Sandie Shaw’s ‘Nothing Comes Easy’ and Julie Driscoll’s classy, Dusty-like reading of The Lovin’ Spoonful’s ‘Didn’t Want To Have To Do It’.

What came next was arguably Revolver’s peak. Yellow Submarine captures a mood of madcap experimentation, wide-eared wonder and naïve, ‘soaring optimism’. Starting life as a fragile piece of home-taped Lennon introspection (‘In the town where I was born, no one cared,’), it was spun into children’s sing-a-long gold by McCartney, before he dozed off to sleep one night. Starr was the natural choice for singer, ‘the knockabout uncle type’ (McCartney), the most Beatle of Beatles, the one who wanted a secret passage in his house that led to all his friends’. Donovan contributed the ‘sky of blue sea of green ‘ line (his own Sunshine Superman album arrived weeks after Revolver similarly infused with India, acid and baroque). 1970’s HMS Donovan would be the culmination of the era’s love of child-song (part of the revival of the Romantic/Wordsworthian view of childhood as an imaginative, innocent Eden).

To bring this nursery rhyme-psychedelic sea shanty to life, Studio Two’s Trap room was raided for noise-making toys on a June evening that was more party than session, the bonhomie culminating in a conga-line. Among the revellers were Marianne Faithfull and Brian Jones, who blew a swanee whistle and clinked glasses. Tiny microphones captured Lennon blowing bubbles in water, chains swished around a full tin bath. Adding to the slightly camp atmosphere were Lennon and McCartney’s nautical instructions midway through, the former also echoing Starr’s final verse, Goon-style sounding like Lord Kitchener’s Valet’s poster had come alive. The brass – a popular sound with Dylan’s recent ‘Rainy Day Women #12 & 35’ – came from the studio’s sound effects library. Its likely original source, a band playing Helmer’s 1906 ‘Le Reve Passe’ was obscured by Emerick’s splicing and vari-speeding. This was English psychedelia’s essence, open to infant and pensioner (Granny was taking a trip too), more Lionel Jeffries than Timothy Leary. Left off the final mix were more sound effects and a Lennon-written storybook spoken intro, predictive of the narration on Small Faces’ Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake.

The Beatles at Chiswick House, London, 20 May 1966 Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

Behind arcana was innovation; a future of sampling lurked inside. Sound effects had been creeping into pop on Joe Meek’s ‘I Left My Heart At The Fairground’, Shadow Morton’s Shangri-Las’ teen melodramas and another big 1966 hit, the Spoonful’s ‘Summer In The City’ vividly dramatized the urban jungle with drills and car beeps. Novelty shrouded radical politics too – ‘Yellow Submarine’’s collectivist utopianism lent itself to left wing protest , adapted by Tariq Ali and striking workers.

The clock was ticking, a tour of Germany and the Far East was looming. The rest of Revolver was cut quickly with minimal experimentation. McCartney’s ‘Here, There And Everywhere’, dashed off by Lennon’s pool, was a tight, Tin Pan Alley-like construction. Unlike that summer’s other heart-string pullers, ‘God Only Knows’ and The Association’s ‘Cherish’, the upholstery’s spare but gorgeous; the filigree of Harrison’s lead guitar filigree, Starr’s delicately brushed cymbals and those heavenly cloisters of three-part Beach Boys-style harmonies (hearing Pet Sounds before its UK release had prompted the song)

‘Good Day Sunshine’, basking in that June’s heatwave, also gently dazzles – its second verse breezily wandering off into Martin’s unexpected, honky tonk solo; the ending’s dropped beat, sudden key change and overlapping canon harmonies, final twists that impressed the venerable Leonard Bernstein. It took old-time music hall and trad jazz and refracted them through a modern, hip, ‘turned on’ lens – the same way its inspiration, recent hit ‘Daydream’ by The Lovin’ Spoonful did. Both McCartney songs then were created by what The Byrds’ Roger McGuinn called the ‘international code’ – the creative energy and competition flowing between the US and UK since The Beatles early American breakthrough.

The Byrds had been present on the August day that triggered the last Revolver recording, Lennon’s ‘She Said She Said’ – a bad trip in LA’s Benedict Canyon where Lennon overheard actor Peter Fonda telling an acid-queasy Harrison he knew ‘what it’s like to be dead’. If ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’’ mystical futurism subscribed to the evangelical Leary’s LSD ‘heaven’ – this alluded to it’s hell – a warning that the voyaging into deep inner space could open up into an introspective abyss.

With pressure mounting; tempers flared during the nine-hour session on 21 June. McCartney exited the studio and Lennon stitched together his ‘sad acid song’ from two fragments with Harrison’s help. It’s a circus of exhilarating horrors – clattering drums, gnawing guitars all jangled nerves and frayed psyches a signpost for the lopsided rock of Low’s A-side. There’s a waltzing time-change – another trick that impressed Bernstein – that flashes back to childhood- the start of a journey backwards and inwards to the primal scream of the Plastic Ono Band.

As LSD use spread, casualties proliferated – sensitive souls forever burned by bum trips, writhing in psychic terror, the unspeakably disturbing sight of a child on LSD witnessed by Joan Didion in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Surrendering to The Void via LSD could enlighten, expose life’s illusions, but it was also a black hole the user could fall into, never to return.

Within days of completing Revolver, after attending the pre-opening party of London’s new ‘swinging’ hotspot, Sybylla’s, The Beatles were whisked away on tour. Emerging from recording’s cocoon, unable to replicate the album live, incurring the wrath of Imelda Marcos in the Phillipines, were all wearying factors that drove the Beatles further from the stage and closer to the studio.

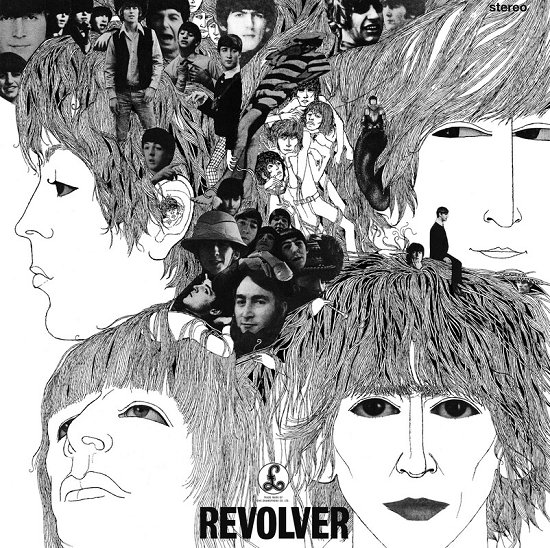

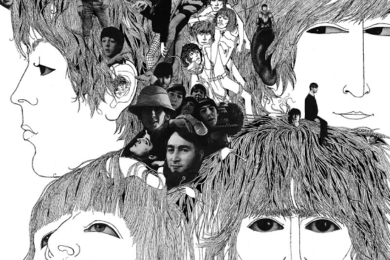

From the Tokyo Hilton on 2 July they sent EMI their seventh album’s title. Abracadabra, Magic Circle and Beatles On Safari were all contenders, but they settled for Revolver – a gun, a spinning record, a whirring Leslie Cabinet – a phonetic cousin to revolution and evolution. A suitably swirling collage of Beatles faces was originally planned for the cover. Designed by Robert Freeman, who’d photographed every album since With The Beatles, it now houses the extras in this new deluxe edition.

They opted instead for an image by Klaus Voormann, a graphic artist, bassist and friend since early 60’s Hamburg . A mixed media marvel, from illustrated heads old Beatles photos pour out; mop-top past now a collective Bosch-like phantasmagoria. It’s a psychedelic inversion – the ‘real’ rendered illusory, the magical a reality. Waves of hair still unite this ‘four-headed monster’ (Mick Jagger), but individual personalities emerge, eyes glance in different directions. Only Harrison looks out directly, a sage, pixie–like presence.

The line drawings recall Aubrey Beardsley, the once-disgraced illustrator associated with Oscar Wilde, who was enjoying a revival that summer at a V&A exhibition (1968’s masterpiece from Hungarian guitarist Gábor Szabó, Dreams featured a similarly Beardsley-esque sleeve.). It’s black and white, just like that earlier 60s ‘shock of the new’ Psycho, because ‘as Voormann says ‘everything else (inside Revolver) was colour’.

In their absence, 60s pop had accelerated regardless – 45s like ‘Shapes Of Things’ and ‘River Deep Mountain High’. Even Joe Meek, then considered passé four years after Telstar, produced singles that now sound prescient, from the fabulous Glenda Collins’ ‘It’s Hard To Believe It’ to the proto-Roxy outbursts on The Riot Squad’s ‘I Take It We’re Through’. The album was threatening to eclipse the single as pop’s chosen format, with Blonde On Blonde, Pet Sounds, The Byrds’ Fifth Dimension, The Mothers’ Freak Out and the underrated Them Again. The Stones had issued Aftermath – the near hour-long sound of 1966, full of Jagger/Richards originals, mostly Brian Jones-supplied exotica (marimba, dulcimer, Koto) and an unhealthy dose of misogyny.

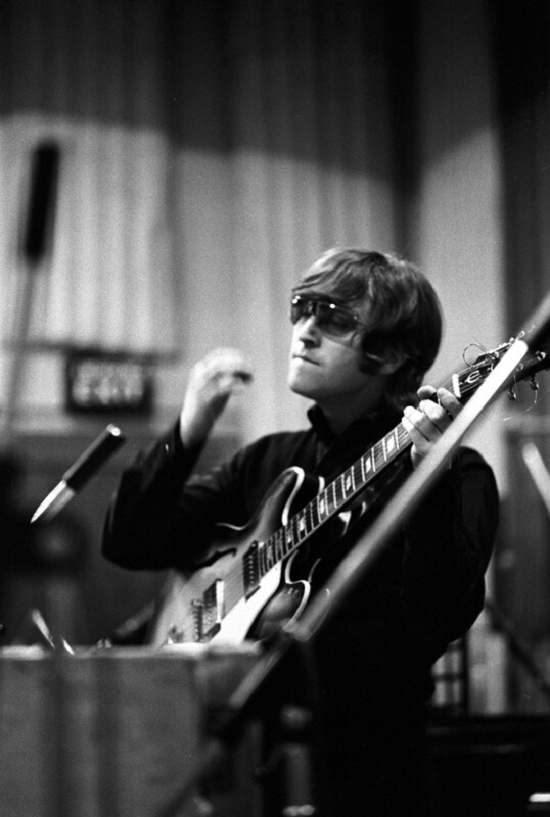

John Lennon in Abbey Road Studios, 1966. Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

But Revolver released 5 August, just six days after England’s World Cup victory hit an imperial bullseye – resting atop the UK charts for six weeks, garnering rave reviews from beyond pop’s sphere – jazz and Classical critics praising its ‘smoking hot newness’, its ‘Purcell tricks’. If The Kinks’ Face To Face that year was a minor masterpiece, Revolver was a major achievement; rich, varied, experimental but uncluttered, every excess overdub or middle eight chopped to create a work of pristine, multi-focal compression.

14 songs barely going beyond three minutes, as pop stretched to four minute 45s, Revolver retained pop’s punchy economy even as it expanded it’s parameters. A deluge of cover singles followed (The She Trinity, The Tremeloes, Cliff Bennett and the Rebel Rousers). The Beatles themselves plucked Revolver’s light/dark extremes, ‘Eleanor Rigby’ and ‘Yellow Submarine’ for a double A-side, issued the same day, also hitting the top spot.

In America, Revolver was overshadowed by the controversy that also mired August’s US tour. Lennon’s ‘more popular than Jesus’ remarks, barely noticed when published in Cleave’s 4 March piece, were incendiary when reprinted in teen mag Datebook and sent to Southern DJs. Boycotts, bans, and death threats ensued, with stacks of Beatles vinyl tossed onto burning pyres. A country divided sent the new, outspoken Beatles mixed messages. Revolver was Number One for seven weeks, Eleanor Rigby failed to make the top 10, a Shea Stadium show was 10,000 down from 1965’s record-breaker. Their performance on 29 August at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park would be their last.

By November they were back at EMI Recording Studios creating the twin peaks of English psychedelia, the ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’/ ‘Penny Lane’ single and Sgt. Pepper, but speculation around a split persisted in the media, and between their US/UK labels. John Lennon’s role in How I Won The War, McCartney’s score for the Boulting Bros’ The Family Way and Harrison’s solo trip to India, and later temporary exit, all hinted at future fragmentation. Reality had seized that swinging pendulum – wages froze, Tara Browne fatally crashed his car, B-sides revealed the ‘other’ London – The Kinks’ ‘Big Black Smoke’, Bowie’s ‘The London Boys’. A year before the summer of love, Donovan’s ‘Season Of The Witch’ warned of something darker already afoot.

Revolver’s influence was immediate, enduring and far reaching. Brian Wilson immediately went back to the drawing board after hearing it and concocted ‘Good Vibrations’. Its fingerprints were all over The Who’s A Quick One, The Byrds’ Younger Than Yesterday and Bowie’s 1967 debut.

When punk hit a dead-end, post-punk and 80s art-pop reached back to it for a way out (The Jam’s 1980 Sound Affects, their finest hour, is the son of Revolver). It continued The Beatles’ dialogue with Black America, covered by Rockwell, sampled by Frank Ocean, ushering in a Beatles period influencing Prince and George Clinton A lodestar to Britpop it may be (‘Rain’ contains Oasis’ DNA, it was favourite of Blur’s Graham Coxon) but Revolver was forged by that ‘international code’.

Prior to Abbey Road stereo mixes were a hastily prepared afterthought, often splashy and crudely separated, but as with other recent Beatles retooling, Giles Martin and Sam Okell’s stunning new Revolver mix doesn’t dramatically reimagine the album but takes you deep into it. Using the ‘de-mixing’ technique devised by Peter Jackson for Get Back to separate individual instruments hitherto confined to one track, you can feel the bows glide across ‘Eleanor Rigby’’s strings, the introductory cymbals on ‘Good Day Sunshine’ burst forth like morning rays streaking through lazy Lennon’s curtains as his partner waits for him to rise.

Revolver transcends boomer nostalgia because the rush of joyous, creative energy that surges through even it’s darkest moments still sounds like tomorrow; ageless, deathless. Because it’s still an escape route from pop and rock’s orthodoxies, hatched while the latter was still forming. Because it dreams of a world where ‘everyone of us has all we need’ are still worth dreaming, Revolver remains a radical masterpiece of ‘smoking hot newness’.

The Beatles’ new Revolver Special Edition is out now