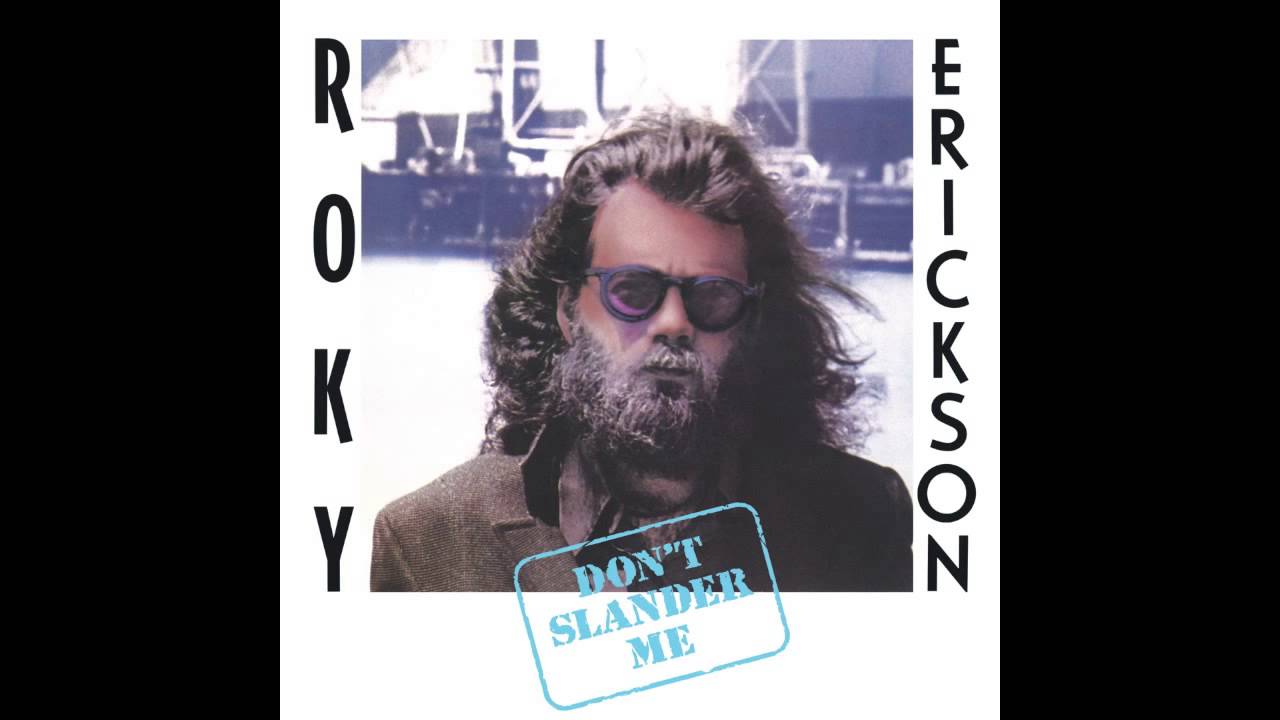

The Thirteenth Floor Elevators are now rightly revered as originators and masters of a particular brand of inspired Texan punk psychedelia. But singer Roky Erickson’s subsequent solo work, though equally marvelous, is often neglected by comparison. Partly this is due to the bewildering nature of his sprawling back catalogue, scattered and duplicated across bootlegs, live albums and semi-official compilations of varying degrees of fidelity. This month however, Light In The Attic reissue three key LPs in Roky’s journey: his 1980 debut, The Evil One, its delayed follow-up Don’t Slander Me from 1986 and the essential compilation Gremlins Have Pictures, released the same year.

Of these, The Evil One is the jewel in Roky’s starry crown. Its fifteen tracks, produced by ex-Creedence Clearwater Revival bassist Stu Cook, and originally divided across two LPs in the UK and US, form the backbone of Roky’s live set to this day. Songs like ‘Night Of The Vampire’, ‘Cold Night For Alligators’, ‘I Walked With A Zombie’ and ‘Two Headed Dog (Red Temple Prayer)’ are classics of what Roky termed “Horror Rock”; minimal, melodic hard rock with a weird, gothic core and lyrics that related Roky’s experience of incarceration, mental illness and enforced medication in metaphors drawn from b-movie horror and science fiction, as well as his own powerful, darkly humorous imagination.

Formed in Austin, Texas late in 1965, The 13th Floor Elevators had all but disintegrated by the end of 1967, having released two incredible albums but tied to an incompetent and controlling record company, mired in poverty and drugs, and constantly harassed by local law enforcement officials. “In the sixties certain police, especially the high ranking ones, really had it in for everybody in the Elevators,” recalls Craig Luckin, Roky’s personal manager throughout the 1980s. “They were more upset by [lyricist, jug player and de facto band leader] Tommy Hall’s interviews and statements, but they kind of singled out Roky, I guess because he was the singer and a little younger.”

Roky had already been arrested several times, and during 1968 his seemingly crazy behaviour led to him being hospitalised on more than one occasion. “It was Tommy Hall’s thing that they should take LSD almost every day,” Luckin says. “Clementine [Hall’s wife and co-lyricist] told me she took 300 trips, and that’s a lot! And I just think that Roky, being younger than Tommy and Clementine, when all of the Elevators were regularly taking it, it had a worse effect on Roky in the long run.”

In February 1969 Roky was busted for possession of a small vial of marijuana – possibly planted – and was advised to plead insanity to avoid a possible ten-year prison sentence. He was bailed but became a fugitive from the law, returning to Austin to play a comeback show in August, where he was arrested onstage after completing his first set. Two police cars were trashed in the ensuing riot, as enraged Elevators fans sought to protect their hero from the police. But on October 8, Roky was sent indefinitely to the Rusk Maximum Security Prison for the Criminally Insane, where he was doped up with Thorazine, given electro-shock treatment and locked up alongside murderers and rapists, 24 hours a day for the next three years.

Roky was released from Rusk in November 1972 and, after an ill-advised attempt to reform the Elevators with original drummer John Ike Walton for a dozen or so gigs, Roky in 1974 put together a new band he named Bleib Alien. He found the musical foil he needed in Billy Miller, who had been a 13th Floor Elevators fan as a teenager in 1960s Austin, and who felt just as out of place as Roky in the self-congratulatory “cosmic cowboy” era that put their hometown on the musical map in the early-to-mid seventies.

“The local rock scene there was kind of disgusting,” Billy Miller says now. “The bands that were popular locally there were bands that no-one will ever hear of again. They were just totally middle of the road, and Roky and I couldn’t have been more unpopular with the musical crowd that dominated the scene.”

Miller’s Elevators-inspired band Cold Sun had recorded a brilliant but unreleased (till 1989) album at Austin’s Sonobeat Studios during 1970. Eight years ahead and four years behind their time, Cold Sun had limped on, playing occasional live shows to a reception of mixed bemusement and hostility from the redneck hippies that made up the in-crowd audience at cool early seventies venues like the Armadillo World Headquarters. But when Miller heard Roky’s new songs he jumped at the chance to work with him, immediately pulling the plug on Cold Sun and folding that band’s final rhythm section of Hugh Patton (drums) and Mike Richey (bass) into Roky’s Bleib Alien concept.

A fan of Joe Meek and Del Shannon as well as the Velvet Underground and the Elevators, Miller’s weapon of choice was a customised, sawn-off electric autoharp – a bastard mutation of the instrument usually clutched protectively to the chest of fey folkies, in Miller’s hands made to emit stinging blasts of b-movie sci-fi space noise, unearthly melodic cascades or pulsing organ-like earth drones, fulfilling the same disorienting, transporting role as Meek’s Clavioline, John Cale’s electric viola, or indeed Tommy Hall’s amplified jug. Miller was a key conspirator in Roky’s plan to fuse the hard-spiked, weird essence of true psychedelia with the back-to-basics, tough-minded rock & roll both could smell on the wind, bearing the first seeds of the soon-to-come punk movement.

Bleib Alien played their first proper show at the Austin Ritz on April 25, 1975.

Miller: “We were forced to put a band together, because I was in Memphis for a couple of months and at that point somebody talked Roky into committing to a gig. And it was a very big gig, it was the opening of the Ritz, and it was the opening of the Texas Film Festival, and we were the house band. And the featured artist was Tobe Hooper, with his new film Texas Chain Saw Massacre. So they couldn’t have found a better local band than Bleib Alien to play at that! And when we began putting it together the only people that I could trust – to not bring in the locals who just didn’t get it, there wasn’t anything happening there then like what Roky and I were into – were the two guys from Cold Sun. They were totally my confidants and musically never a problem, never questioning the direction or whatever. And I knew that with Roky they would not question the direction or the type of music. I mean, Roky was, nobody took him seriously, until we did that first gig, and then people started taking us seriously, and they wanted a piece of it, they wanted in on it, and it was fortunate that Roky left Austin when he did, because there was just nothing there for him. There were just people who wanted to water down what he was doing.”

Before that fortuitous departure from Austin however, Roky went into a local studio with the legendary Doug Sahm, frontman of 1960s Tex-Mex survivors the Sir Douglas Quintet, to cut a raw, lo-fi blast of a debut solo single, ‘Two Headed Dog (Red Temple Prayer)’ backed by ‘Starry Eyes’.

“When you listen to that now – ‘Two Headed Dog (Red Temple Prayer)’- it’s very punk sounding,” Miller says. “And Doug totally went along with that. He totally directed that whole session, and I truly owe a whole lot of that to him. It was a wilder version of what we were doing live.”

It was the connection with Doug Sahm that provided Roky’s ticket out of Austin. Craig Luckin, an Elevators fan since high school, was working as Doug’s tour manager out in San Francisco when he first heard from Roky Erickson. Roky wanted to perform with the Sir Douglas Quintet at their forthcoming three-night stand at the Palamino Club in North Hollywood, and wasn’t going to take no for an answer.

“It all sounded plausible to me, and basically I agreed to everything Roky suggested,” Luckin recalls. “I got him the round trip air fare and reserved him a room where Doug and the band and I were staying, and it all turned out really well. Roky did amazingly well at all three nights, doing his four songs with Sir Douglas backing him up: ‘Two Headed Dog,’ ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me,’ ‘Don’t Shake Me Lucifer’ and ‘Starry Eyes.’ And not only was he able to perform good, he was wonderful backstage with all the celebrity guests, and more importantly with all the press people that were there. Quite a few hip underground rock newsletters and local small press publications interviewed him, which kind of helped things later on for getting concert dates for Roky And The Aliens in the LA area.”

Indeed, Roky enjoyed himself so much in California that he didn’t want to go home. Luckin: “After the Sunday night I’m ready to take him back to the airport to fly back to Austin, and he’s going, ‘No, no, no, I’ve got to come up to your house, with Doug and [guitarist] John Reed.’ And so he did, and that was kind of a whole enjoyable week. But once we got to San Francisco I found out what his whole motive was, which was to talk me into being his manager. He accomplished that, and then he flew back.”

Roky soon returned to San Francisco, bringing his new wife Dana with him, and set about assembling a new band with Luckin’s assistance. Guitarist Duane Aslaksen was Doug Sahm’s sound mixer and guitar tech; Luckin had sent him to meet Roky at the airport and the pair immediately hit it off. Bassist Morgan Burgess and drummer Jeff Sutton soon joined, but Roky felt there was still something missing.

“We’d done maybe five or six shows around the Bay Area,” Luckin recalls, “and then one day Roky said, we’ve got to have Billy Miller.”

Miller: “I was in Memphis, and he played one of the songs over the phone, and I was sold, right then. But my advice to them was they’d be crazy to get one more guy. They don’t need me, they don’t need an extra person; it sounds perfect the way it is. And they were actually determined to get one more person; a keyboard player or something, a horn player maybe, anything atrocious to ruin that perfect sound. So I thought well, if that’s what they’re going to do it should be me. And so eventually I think the band – I got a lot of attention, I think the band stood out because of me, but I’m still not sure that it wouldn’t have been better without one more person.”

It was Miller who christened the new group the Aliens. “Most disc jockeys by the mid-seventies, they were total assholes,” he explains. “If they got something in the mail, it didn’t matter who it was from, if it was a name that they couldn’t pronounce, they’d toss it right in the trash. And if they thought it was psychedelic, they’d toss it right in the trash, because that was last year’s thing. And these were guys were hip; these guys were up and with it. And they were all just really sleazy, payola-taking, strip club travelling sleazeballs. And I was afraid that we would never get any airplay if it was called Bleib Alien, because these guys are dicks. They’re not going to play something if they don’t know how to pronounce it.”

The Aliens initially released two 45 singles in 1977; ‘Bermuda/The Interpreter,’ produced by John X Reed, and an EP on the French Sponge label produced by drummer Jeff Sutton. But by the end of that year they’d begun working on demos with former Creedence Clearwater Revival bassist Stu Cook, at his studio space Cosmo’s Factory. Cook: “I got involved with Doug Sahm when my partner Doug Clifford, Creedence drummer, produced the album Groover’s Paradise [by the Sir Douglas Quintet, 1974]. I played bass on the album, and the fellow who was tour managing Doug Sahm also became Roky’s personal manager, Craig Luckin. We agreed to work together, with Roky and his band the Aliens, to shape the material and select songs and work out arrangements with the band. The Aliens would come down to Cosmo’s Factory and rehearse there and work on the songs, work on their live show and so on. We just took it a step at the time until we felt comfortable with the idea of working together.”

Though an experienced musician at this point, Stu Cook’s production experience was limited to recording a dozen demo songs for the Bay Area band Clover, soon to decamp to England and back Elvis Costello on his debut album, before spawning future soft rock superstar Huey Lewis. So The Evil One was Cook’s first proper album production, and it was definitely a case of being thrown in at the deep end.

“My input was to take Roky’s ideas and carve them into songs, with verses, choruses,” Cook says. “The hardest part was straightening out the lyric. I had to take a lot of liberties with Roky’s songs from the lyric point of view, to put them into a cohesive story sometimes. Roky was starting to get a little more inconsistent as the process went along, and so as we got closer to the finish line it became more and more difficult to get there! Craig and I had to spend hours trying to piece together songs, in some cases, so that they made sense. They didn’t always end up in the same order that Roky revealed them in.”

“Roky never heard some of the songs, how they came out, until he got a copy of the record. I just decided to run a tape all the time, because I never really knew when the magic was going to appear, when the Roky that I needed was going to be there. Because he was getting more and more distracted by things in his personal life, and it was getting sometimes very difficult to focus on the album. This was before digital editing, so I would have to wild sync in, and that was a tedious process; start one machine, start the other machine, hit record, do it again because it doesn’t feel right, it doesn’t have the swing on it – some of the songs came together like that.”

Craig Luckin: “Roky had stopped taking his prescription medication, and I remember Duane and I were kind of supportive a little bit of Roky; I don’t know if we should’ve been, but we were a little supportive of him not wanting to take that medication, because it seemed like it was really strong. When he started taking it, it seemed like he had no energy. He wasn’t ever misbehaving, but also there were none of the fun, exciting performances- you know, in hindsight I don’t know if we were wrong about that. But he did stop taking it, and then he seemed to be doing great.”

“It would be when we really started to do a lot of shows in the Bay Area that the problems happened. I can remember doing a show at the Long Branch Saloon, I think we were opening for Tom Fogerty, and we were to do two sets. Roky did a great first set, and then some fan intercepted him on the way back to the dressing room and gave him something, I don’t know what. But he came out for the second set and I’d never seen him like this, before or since. His eyes were rolling back in his head, he could barely hold his guitar, let alone sing. So that became something that Duane and I especially became aware of, going forward. Because of the legend of the Elevators and the legend of LSD, which has much more to do with Tommy Hall and Clementine Hall, the lyricists; you know, Roky wasn’t writing songs about LSD. He wrote a lot of the music, but he didn’t write much of the lyrics. And anyway, because of that there were all these little fan boys that were into LSD or whatever that were like oh boy, I get to meet Roky Erickson, let’s slip him something. And it wasn’t always LSD either; it would be heroin, or sometimes he’d act like he was on speed or something, and in the end, even if it wouldn’t necessarily ruin that performance, he wouldn’t get any sleep the next night, and then he’d just be in a really bad mood. So that was the biggest problem; maybe well-intentioned but harmful interaction with the fans.”

Eventually it got to the point where the Aliens quit and went off on their own, and Luckin had to send Roky back to Austin, where he found himself forcibly hospitalised once again.

“More than once, that happened,” Luckin recalls. “It happened in San Francisco too, at least once, where it’d be the same kind of thing, you know; the cops would get him late at night, and he’d be acting crazy, and they’d just give him immediate commitment. I think in California at the time it was a thirty day minimum, but in Texas it was more like ninety days. This was when we were still in the middle of recording The Evil One, and we’d pretty much got all the overdubs done, you know the solos and so on, and the basic tracks, but we didn’t have good lead vocals from Roky on all of them. And he had been back in Austin and had gotten picked up at night, you know, for doing something weird at three in the morning walking around, and had got committed for ninety days. And so after he’d been there for maybe sixty days or something, I got another one of those phone calls, just like that first phone call when I first met him, you know, it was from a pay phone again, only this time it was a pay phone in the mental hospital. And he said hey, Craig, why don’t you and Stu bring the tapes down, I’m ready to do the rest of my vocals. And so we did, we flew down with 64 boxes of 16 track reel to reel. I don’t so much blame Roky for any of this, it was just all part of who he was, and even the crazy parts are part of what makes him a great songwriter.”

Cook: “I came down to Austin and put on a coat and a tie and went over to the institution where they had Roky locked up, and I would check him out. And several of the other inmates, patients, they thought I was a doctor and they tried to get me to get them out. I would spring Roky and we would take him down to the studio and we would work on vocals. And when he would stop being productive I would be like, okay Roky, go have dinner and go back home, got to check you back in. See you tomorrow! We did that for a week. It was, in a lot of ways, a very unusual project.”

According to Billy Miller, there were other difficulties too. “Once the CBS record company launched, they got involved, and every time they would increase the budget we would go back into the studio, fixing things up,” he recalls. “The songs from 1977 were the songs with Jeffrey Sutton; those were not put together in the studio, they were performed live in the studio, and that’s why ‘Sputnik’ and ‘Bloody Hammer’ sound different than the other songs. Without Jeffrey Sutton, the band just fell apart. Jeffrey seemed to boss people around; he was kind of a bully. When Jeffrey was gone Duane more or less took over, and he wasn’t an arranger. He was a natural born rock star, but only if someone else was in charge, telling him what to do. And without the bully, things were not as good. Not because John Oxendine [AKA Fuzzy Furioso, Sutton’s replacement on drums] wasn’t a great drummer; he was, but Jeff was more than a drummer. He was a bully! No, he was a leader, and he knew that we needed leadership.”

The ten track album was originally released by CBS in the UK only in 1980, its title obscured by artwork that has led to it being known variously as TEO, Five Symbols, Runes or simply Roky Erickson And The Aliens. A year later, 415 Records secured the rights to a stateside release, but decided that they wanted five extra tracks- “Just so that people who already had one album would have to buy the second one,” according to Craig Luckin. Stu Cook took the two Jeff Sutton produced demos and remixed them, overdubbing his own bass lines onto the originals, and three outtakes were also added, so that the two editions of the album had five songs in common but also five different songs on each. The new edition finally compiles all fifteen tracks together on one release.

Roky And The Aliens would go on to record Don’t Slander Me in 1983 before going their separate ways, in Roky’s case descending into a well-documented period of illness and adversity that would last nigh-on twenty years. His re-emergence in the mid-2000s seemed nothing short of miraculous, and resulted in a well-received new album as well as a third act as a solid live performer able to play all around the world, but still drawing largely on the songs originally recorded as The Evil One for his set list.

Stu Cook: “I’m hoping that this time around Roky will get the recognition for that body of work. It’s sort of an underground classic, but it deserves to be more widely appreciated. Like I say, it might seem dark but it’s done with a beautiful sense of humour. Those songs were very important to Roky at the time, and they’re like his children. So that’s a very important part of Roky’s life, and it is great stuff as well, and that’s why it is, as you say, the backbone of his live performances, and the arrangements still hold up. They weren’t dated in any fatal way, so when the band fires those songs up and Roky steps up to the microphone, he can still make that happen.”

Craig Luckin: “It’s been at least six years since there’s been any craziness for Roky now. I don’t know if he learned his lesson or what, but now he’s able to just say no. And so he’s doing great, and is able to tour the world, things that – we could never get across the Mississippi river when I was working with him. He’d pretty much play in Texas and then in California and that was it. And then it would be off and on. But yeah, now he’s doing really good, and I’m happy for him.”

Billy Miller: “This is a legit interview we’re doing right here, and this is in the year 2013, and Roky is doing well and doing a lot of tours, and we have these three albums with him that are about to come out, so this is totally the time to be telling things. But keep in mind these are things that have been deliberately suppressed for years, for good reasons, I think. I mean it’s in Roky’s best interests to keep all this stuff under wraps when there’s nothing to do with it. If I’d have revealed all this stuff some years ago, no-one would’ve cared, it just would’ve been a wasted thing. And then it would’ve been repeated over the years until it became inaccurate, like a lot of this stuff. But I think we’re doing the right thing.”

The Evil One, Don’t Slander Me & Gremlins Have Pictures are out now on Light In The Attic

Thanks to Stu Cook, Craig Luckin and Billy Miller for their time and input, and to Will Lawrence at In House Press. Visit Light In The Attic.net for further information