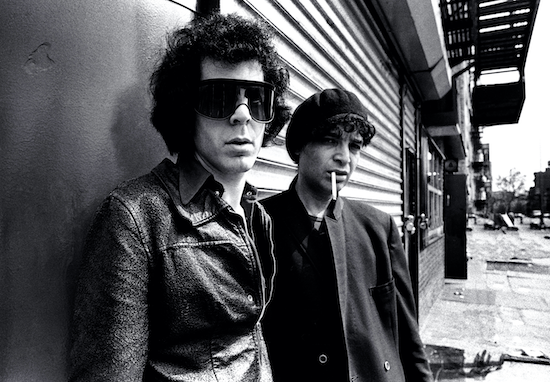

Suicide by Adrian Boot

"Hey! Gotta cigarette? A CIGARETTE!"

A deranged man is screaming in your face as you walk through the Mean City’s back streets. Is this Glasgow? Am I home again? Are we, as Alan Massie once suggested, in the most Easterly city in America? No: this is one of the voices conjuring the crazed spirit of the original megalopolis on the Hudson. This is Alan Vega from Suicide berating us: his voice instantly recognisable with its loopy whoops, its frightening, feral yelps.

"A CIGARETTE?" Vega’s urgent demand comes from a track called ‘Dominic Christ’. His aggressive tone recalls scary late night encounters with psychotics marinated in Buckfast, debauched evenings in the vicinity of Glasgow’s Barrowland Ballroom. The city may double for Gotham in the new Batman movie but this music with Vega’s vocal is the authentic soundtrack of degenerate late 20th century New York City. Vega barks at us and we can’t escape his echoed shrieks as if they bounce from wall to wall in some dank abandoned alley. We feel acutely claustrophobic. Better give him that free fag fast and beat it out of here, pronto.

‘Dominic Christ’ is the opening track on Surrender, a new compilation of music by Suicide – a perfect introduction to recordings made by the outrageously innovative duo. Martin Rev and Alan Vega intermittently worked together from 1970 until Vega’s death in 2016. There’s not enough space to list musicians they’ve influenced: it’s just about everyone you rate with a synthesizer. In ‘Dominic Christ’ we hear Vega bellowing like a jakey high on methylated spirit, aflame with religious fervour, demanding repentance. Rev’s unbalanced rhythm track reels unsteadily like a drunkard’s gait. You’re reminded of Glasgow again: the sorry sight of a rubber man lurching over the road from the Saracen’s Head pub to terrorise stragglers from the Barrowland. You see a double decker bus hitting the ataxic punter square on: SMACK. His pals cry out in angry despair, voices not unlike Vega’s… AW FIR FUCK’S SAKE, ALLY!

Suicide were always going to be big in Glasgow; Suicide made sense in Glasgow. My first encounter (aged 16) was in a record shop called Listen. One of the guys behind the counter played their debut album; the track sounded like someone being tortured or murdered: ‘Frankie Teardrop’ of course. Was this a Glaswegian field recording? Could these screams have come from one of Arthur Thompson’s victims? Thompson, the city’s capo di tutti capi, allegedly crucified enemies by nailing them to doors. I couldn’t get back to the New Town safety of East Kilbride fast enough. A decade later the guy behind the counter became my boss. I think I bought a wussy album by Stackridge much to his distaste.

By the next decade, the 1990s, Suicide’s influence on Scottish electronic music was lapidary, immutable. By that time Paul Haig from Josef K had covered ‘Ghost Rider’ and ‘Surrender’. Robert Rental and Thomas Leer made quick acknowledgment of their own debt. Recently Bobby Gillespie’s memoir Tenement Kid lavished praise on Rev and Vega, arguing the sound on their second album predated/predicted house music. Even sedated East Kilbride got in on the act with The Jesus and Mary Chain tapping wholesale into Suicide’s unholy angst, their stormy maelstrom of annoying noise.

Rev knew Glasgow was home territory saying later: "It was such a rough place and people used to say, ‘If you can survive Glasgow, you can survive anything!’” A hatchet was thrown at them when they played the Apollo theatre in 1978. This story should not be doubted: young neds in the city are known to carry swords. Suicide found Edinburgh more genteel. There were disco balls, there was dancing. Edinburgh dug the sleek pop genius of the second album but Glasgow recognised itself more in the tunes on the debut – a stark, troubled, sometimes sexy, sometimes frightening, place.

We take it as read today that Suicide is to the 1970s what the Velvet Underground is to the 1960s, that is to say the NYC sonic exemplar of choice. But this perception wasn’t always the case. Contemporaneously the pair was despised: most unable to accept synthesized ‘rock’. What was initially thought to be incomprehensible was revealed, in time, to be basically quite traditional. Suicide’s musical roots in 1950s doo-wop are easy to trace. Vega’s vocal mannerisms hark back to the revelations from Sun Studios. The band’s unique trick was to combine Elvis-like crooning with drone influences from the likes of La Monte Young and John Cale. Martin Rev’s Farfisa organ stabs borrow pop nous from the likes of ? and the Mysterians. Paradoxically these antediluvian pilferings made Suicide the sound of the future. This compilation proves Suicide were ahead of the pack. And it is also true to say they were very much in tune with the American art scene of the period. Suicide might even be regarded as late Pop Art, younger brothers in spirit to Andy Warhol.

Suicide have much in common with the man who famously said he wanted to be a machine, not the least of which is a mutual love for repetition and industrial aesthetics. Vega is quoted (in David Nobakht’s book, Suicide: No Compromise from 2005, the source of much information in this essay) as saying: "The first time I saw the soup cans, it was like holy shit – one of those breakthrough times in your life." Vega was tempted to get involved with the Factory but his own individuality, his sense of his own artistic importance, held him back: "I heard through another musician that Andy Warhol wanted to meet me. I hated the idea of all those people hanging around Andy… I did really want to go, I loved Andy Warhol’s work, but I didn’t want to be part of the Factory scene." He went on: "I had seen a lot of people go into that place as one kind of person and come out a lost soul… I am a stronger person than that." He needed to be, what with young Glaswegians toting tomahawks aimed at his head.

Vega’s art credentials are serious. Ad Reinhardt taught him. Jeffrey Dietch, the noted NYC dealer, represented him. He had his sculptural works shown at the Karp gallery. In time he’d even appear at Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Art on Sauchiehall Street. Some of his assemblages, with their encrusted trash, can be viewed as coruscating comments on American society; the work comes from the same scabrous mould as Ed Kienholz or Cady Noland. In stage performance you could be forgiven for thinking Vega a cousin to the Viennese Actionists with his spectacular displays of self-abuse. Watch him thumping away at his cheekbones with the mic. These self-pummelling performances, all that facial clobbering, sometimes left him blood-splattered. We recall Warhol’s movies like Vinyl (1965) with their scenes of violence, or Paul McCarthy’s video work Rocky (1976) where he boxes himself. Vega and McCarthy’s art: the ne plus ultra of male toxicity.

Other parallels with Warhol can be made explicit. As a compilation ‘Surrender’ covers mutual ground: take religion for a start. Warhol’s Christianity is well attested as evidenced by his late Last Supper works. That opening track, ‘Dominic Christ’, is one of several songs where Suicide toy with Catholic iconography. Jesus is regularly referenced; as the archetype of suffering, a metaphor for being up against it, his crucifixion a metonym for cruelty. Many of Vega’s sculptures are neon-lit crucifixes – imagine a Jason Rhoades construction for a Sicilian Easter. Not to be outdone Rev made an album called Stigmata in 2009. The fascination with Judeo-Christian themes that Warhol and Suicide share is Janus-faced; they can appear pious at times, vaguely blasphemous at others. Ambiguity is all but somehow a kind of faith wins out. Rev talks of the early track ‘Junky Jesus’ and how the pair made a ritual out of performance, what he called "a very static, religious experience".

Suicide also shared Warhol’s interest in death and disaster. The duo take Warhol’s silkscreens, those monochrome shots of horror – the electric chairs, the car wrecks – and give them back to us in Technicolor as with the widescreen madness of ‘Frankie Teardrop’, heard here in an earlier version featuring Frankie as a troubled detective. Andy Weatherall thought it "the scariest record in the world".

If we might point to a historical image that chimes with Suicide’s art it might be the infamous photograph of gangster Dutch Schultz after he’s just been shot. Dutch is exquisitely suited, his fedora tilted, and he sits with his arms sprawled on the fresh linen of a restaurant table. The shine on his shoes is impeccable. The mirror on the wall behind him is smashed by bullet holes. Suicide are a sound equivalent to this scene – theirs is an enthralling voyeuristic mixture of glamour and horror, a heightened acousticophilia, a fetishized auralism. As with Warhol death is not so distanced – it’s in your face. The violent deaths of ‘Frankie Teardrop’ mirror those of Warhol’s silkscreens where bodies lie under cars, where a woman is embedded in a car, a suicide.

Then there are the antipodal delights of life. Warhol and Suicide had a joint fascination with glamour as typified by ‘Diamonds Fur Coat Champagne’, a groovy jet-setting glimpse of the good life. Vega once assisted his father, a diamond setter, so he knew the attraction of gems and their shimmer. There’s loads of sex here too, as represented by the scorchingly sleazy erotics of ‘Girl’, ‘Touch Me’, and ‘Cheree’, the latter memorably described by John Lydon as "Je t’aime with tape hiss". Vega’s crooning, his slithery moans, his dirty grunts, acts in seductive opposition to the fear tactics of ‘Frankie Teardrop’. Suicide’s sticky low-rent depictions of desire predate the likes of no-waver Lydia Lunch, or the sordid shenanigans seen in Richard Kern’s movies.

Suicide had a fascination with speed and technology too: there’s an amphetamine buzz to tracks like ‘Rocket USA’ or ‘Ghost Rider’. And we think again of Warhol’s machinery obsession and destruction – gonna crash, gonna die – a fatalism that seems wholly prophetic as we doom scroll events today predicting imminent nuclear war.

As with Warhol the sociological is never far away. Rev has admitted that Suicide’s work has "always been a commentary on America". David Nobakht writes: "Both Rev and Vega were young children in the era of McCarthy, the Korean War, Sputnik, the Polio Vaccine, and Brylcreem." Readers of Philip Roth will know the terrain. As with Roth we can follow America’s recent history through Suicide’s work. Take ‘Harlem’, a dread description of repression and institutional racism, that has its visual equivalent in Warhol’s ‘Race Riot’: "Mr. Mafia Man got the money… Mr. Policeman got the money… Those beautiful children, they’re eating the rats… Kids ain’t dancin’ no more… The kids ain’t laughin’ no more."

Or see them live on YouTube at Hurrah in 1980 doing ‘Ghost Rider’, Vega looking like Harvey Keitel’s pimp character, Sport, in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver singing "America, America is killing it’s youth." Suicide sang of America and its poisons – the police harassment of ‘Mr. Ray’, the Vietnam Vets and Hells Angels heading on down the highway in ‘Rocket USA’ and on to the paranoid post 9/11 landscapes of ‘Wrong Decisions’ and ‘Dachau Disney Disco’ taken from their last album, American Supreme (2002).

Suicide had much trouble with their name for obvious reasons – the act is tragic, and the word, used unthinkingly, can be utterly insensitive. Pop music usually operates as a placatory, life-enhancing, medium. But pop tells lies, pop is delusional, and Suicide were the truth. Maybe it took more than two decades for their work to achieve proper appreciation precisely because their main subject is our multiple failures as a species, a fact becoming much more obvious in the 21st century. Today our tendency to self-destruct is palpably, horrifically, manifest. We’re all Frankie’s now. But will we get a shot at redemption? Dream Baby Dream…