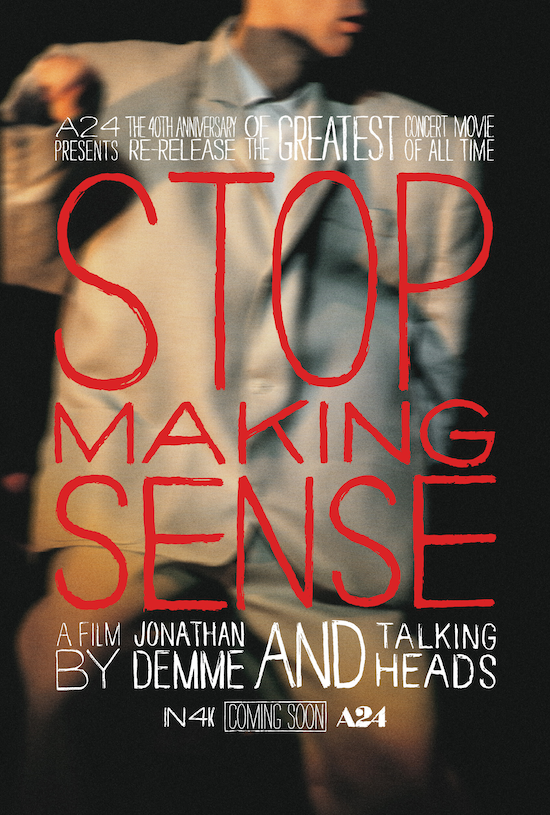

Yes, yes, yes. Obviously Stop Making Sense is the finest concert film ever made.

The 1983 staging of the Talking Heads’ live show is brim full of groove, charm and joy. The band, temporarily expanded from a four piece to a nine piece, are on fire; tighter-than-tight yet not tightly-wound. Frontman David Byrne exudes a captivating charisma, moving over the course of the film from the edgy isolation of his solo ‘Psycho Killer’ through to the transcendent collective prayer of ‘Take Me To The River’. Lighting, back projections and other visual effects bring out the precious uniqueness of each song without ever making the musicians bit parts in their own story. It’s a tribute to the skill of director Jonathan Demme that he was able to capture the sweaty immediacy of a live show while also making it look unlike any live show you’ve ever seen.

And so many moments! Byrne dancing with a lamp, the big suit, the playfulness of the Tom Tom Club segment, the funkified genius of Bernie Worrell and Alex Weir, the intimate grins between the big family on stage…

Now the film is available in Imax and a new cinematic release what is there left to say other than go see it?

Well yes you should see it, if you haven’t already. But how you see it deserves some thought. Because Stop Making Sense, viewed as a historical document, is a work that deserves not just to be celebrated, but also viewed with an elegiac sadness.

I’m not referring to the fact that the band never went on the road again after the tour that culminated in the shows filmed at Los Angeles’s Pantages Theatre 13 – 18 December 1983 (although that is still sad). I’m not even referring to the argument that, given the variable quality of the three studio albums that followed Stop Making Sense, Talking Heads were ‘never as good again’ (although they probably weren’t).

What I am suggesting, though, is that Talking Heads – and David Byrne in particular – were never as interesting again. In fact, I’d go further: By the time the live show was filmed, the band had already lost some of their edgy vitality. While we should celebrate Stop Making Sense, we should also mourn how it signalled the loss of something precious and unique about Talking Heads and David Byrne.

I admit it; this sounds like artier-than-thou point-scoring. But there is something real at stake here. Since the band collapsed in the late 1980s, Stop Making Sense has come to define Talking Heads more than anything they ever did (even the round-breaking ‘Road To Nowhere’ video from 1985 doesn’t resonate like it once did). It was no surprise that, at their induction into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2002, the versions of ‘Burning Down The House’ and ‘Life During Wartime’ that they performed are modelled on the Stop Making Sense versions. The current publicity over the film’s reissue is likely to deepen the tendency to treat it as the ‘definitive’ record of Talking Heads. And that doesn’t really do justice to how extraordinary the band was throughout their career and particularly in the years before 1983.

It’s worth having a look at a much less celebrated Talking Heads concert film. Cinematographically, it’s of indifferent quality. It will never be given an IMAX release. It’s not slick. There are no interesting back projections or startling lightning effects. The staging is downright awful; there doesn’t even seem to be a drum riser. The musicians on that stage often seem ill-at-ease with each other. And yet, in its own way, it’s as spine-tingling and captivating as Stop Making Sense. In fact, on ‘The Great Curve’ – a song not included in the 1983 film – they seem to exceed the highs of their performance three years later.

The film is a TV broadcast of Talking Heads’ show in Rome in 1980, during the Remain In Light tour. The footage, along with another filmed show from Dortmund earlier in the tour, is an indispensable record of an audacious period in the band’s history. By this point, they had left behind much of their austere minimalism of their first album 1977 and, in their three albums recorded with Brian Eno – More Songs About Buildings And Food (1978), Fear Of Music (1979) and Remain In Light (1980s) – they had recorded some of the most extraordinary and innovative music of the period.

That creative purple patch also created tensions within the group. David Byrne began to chafe at the constraints of band democracy. His close partnership with Eno – which also resulted in their collaboration My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts (1981) – increasingly marginalised his three bandmates, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz and Jerry Harrison. This lead to a dispute over the songwriting credits on Remain In Light that was never really resolved.

The most extraordinary Byrne move, though, was adding Busta Jones as a second bassist during the 1980 tour, alongside Tina Weymouth. While the multi-layered tracks on Remain In Light certainly required an expanded lineup (and they added four musicians in addition to Jones) and it’s true that Jones’s funk bass did add something new to the sound, it remains an act of unparalleled insensitivity at best. And you can see in the Rome video just how uncomfortable she was onstage. Much of the time she looks frail and morose as Busta Jones dominates the bass sound.

Byrne may have come to dominate Talking Heads as a unit, but in the Rome video he doesn’t dominate the stage as he does in Stop Making Sense. In fact, no one person does. The band meld into a single unit. They are somewhere else. Somewhere beyond. Everyone looks a bit uncomfortable, Weymouth more than anyone, but that doesn’t seem to hinder the spiralling transcendence of the performance.

When you compare the Rome show with Stop Making Sense, you find a paradox: When Talking Heads were an uncomfortable group of awkward individuals, battling for control, they gelled into something greater than the sum of their parts. Yet on the 1983 film, with Byrne now the unchallenged focus, the band come across as happy, relaxed and having fun.

I have a theory here. I think that Stop Making Sense is actually a document of a band that has given up. Or at least Tina Weymouth has.

One of the most remarkable aspects of early footage of the band, before the expanded lineup and even before Jerry Harrison joined, is the almost frightening intensity with which Weymouth has his eyes locked on Byrne throughout their performances. It’s not an easily decodable look; a mixture of love, hate, awe and resentment.

Compare that look to the Byrne-Weymouth duo performing ‘Heaven’ on Stop Making Sense. Here, she radiates a certain peace, a kind of respect for Byrne, even though her anger at him appears undimmed.

For Weymouth and her bandmates, ‘giving up’ meant accepting that Byrne had become bigger than the band. Weymouth, Franz and Harrison had become Ringo – absolutely crucial to the sound and the onstage dynamics, yet fated to be hitched to an extraordinary talent who could survive without them. While the Byrne-less Tom Tom Club segment on Stop Making Sense is an absolute delight, if you listen to any of their albums it’s clear that Weymouth and Franz’s solo talents stop at occasionally lovely singles.

Perhaps Weymouth spent most of the show waiting for her moment when she got to do the crab dance on ‘Genius Of Love’. Either way, she comes across as a pro, someone who has reconciled herself to the demands of showbusiness, as an engaging sidewoman hitched to Byrne’s wagon.

Some critics have claimed to find a narrative in the film: An isolated and lonely Byrne finds relationship and joy, emerging from his lonely chrysalis into a confident and ecstatic artist.

I don’t know whether that was the intention; still it’s clear that Byrne was emerging into something new. Yes, he seems to perform eccentric oddness, but it’s a tamed oddness. Watching the Rome show and earlier performances, you witness the difference between genuine discomfort in one’s own skin and performative kookiness.

Byrne’s post-Stop Making Sense career, both as part of Talking Heads and as a solo artist, has taken him still further away from the other-worldly artist of his early career. His voice, once thin and emotionless, has matured into something expansive; he is quite the crooner now. And he evokes joy in what he does and in his acclaimed show American Utopia he sets out, quite explicitly, to make himself and his audience happy.

In later life Byrne has spoken of his autism. There’s a debate amongst autistic people as to how much one should be expected to ‘mask’ in a neurotypical world. Was the psycho killer the one who masked, or is it today’s inspirational crooner or is it neither or both? That’s obviously unknowable but there’s certainly dangers inherent in viewing Byrne as having been ‘redeemed’ from the disconcertingly alien performer we saw in his early career. In that respect, Stop Making Sense may not represent Byrne’s liberation but his assimilation (or surrender) into the world of the normals.

I guess it’s churlish to bemoan Byrne’s happiness. And if Weymouth, Franz and Harrison accepting their status as Ringo is what it took to make Stop Making Sense such a wonderful thing, then I am okay with it too. But I do worry that, when we remember Talking Heads through the 1983 film, we are forgetting the band that played in Rome in 1980; a band that, through some strange alchemy, turned conflict and discomfort into something uniquely powerful.

A 4K restoration of Stop Making Sense is in select cinemas now