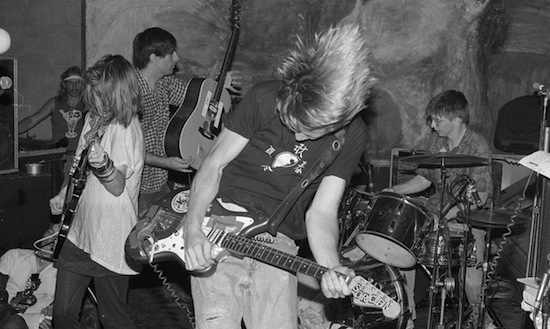

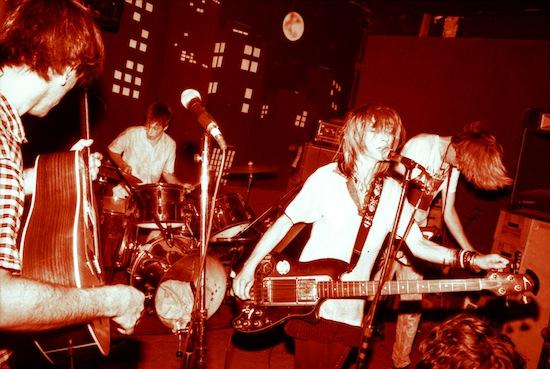

Main photo – B&W – of Smart Bar gig kind courtesy Steve Koress Other live shots thanks to Pat Blashill

Late in 2012 Sonic Youth released a live record, recorded at the Smart Bar in Chicago on August 11, 1985. This article is a trip back to that night, but before we embark, guitarist Lee Ranaldo sets the scene of life in SY and America in 1985. "Well, first of all, let’s not forget it was pre-internet. Whatever ‘underground’ network of musicians there was came about by meeting folks face to face at gigs, or via snail mail postcards or zines. The USA seemed even larger then and it was mysterious how connections were being made. That said, the scene was quite tightly knit, those of us working in music then – everyone seemed to meet and get to know everyone else, and everyone was kinda rooting for each other to succeed, which meant artistically, as there was really no money to be made. It was all a matter of keeping the band going so there was the opportunity to do more work. There was only the slightest fledgling ‘indie record’ scene then, but certainly what bands did get vinyl released had a kind of calling card to go places and get a little bit known."

Smart Bar Chicago 1985 proves to be an interesting release for many reasons. In terms of lineage, it is almost equidistant between the just-released Bad Moon Rising and the soon-to-be-released EVOL. As such it marks a pivotal moment in the group’s career, just as they were hurtling towards a time that many claim to be their defining artistic period. A major factor in this transition was the introduction of drummer Steve Shelley as a permanent figure in the band, replacing Bob Bert who, according to a statement to Flipside captured in Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could be Your Life, was "getting kind of bored", also adding "I was really broke and I just wanted a change of scene" – a scene that Thurston Moore described as "sleeping on floors covered in cat piss every night".

This recording captures Shelley only ten shows in, so new to the band that he recalls almost missing being on the other side: "I wish I had been there, seriously, I was so new to the band I was just giving my all to make it happen." Listening to the recording, there are moments when Shelley’s playing teeters between saturated exertion and complete collapse. Capturing the gusto of a band early on in their career is one thing; capturing a show featuring a newly inducted member, whose performance is also entrenched in the desire to prove their worth, is something else. The cementing of Shelley behind the sticks in SY proved not just a missing piece to the puzzle – it was closer to someone showing up with the missing instruction booklet for the game itself.

Michael Azerrad wasn’t present at this show, but recalls catching them for the first time a few shows down the line, at New York’s CBGB. "These were pioneer days." He too remembers the impact of Shelley’s inclusion. "I remember thinking that Steve played kit drums almost like tablas — very few cymbals, and busy, ingenious tom-tom patterns played with shuddering force. It made the extended musical passages almost raga-like. Except very loud and extremely intense."

"Our style was coming into flower in this period," says Ranaldo, "and Steve was no small part in cementing that. His addition really stabilised and focused the band, right at the time we were really figuring out our ‘sound’ after the early enthusiasm of the Confusion and Kill Yr Idols period."

‘Intro/Brave Men Run (In My Family)’

Azerrad believes it was this period that gave birth to the group at their greatest strengths. "This was a pivotal, transformational time for Sonic Youth. They had become vastly better musicians – both in terms of playing their instruments and in terms of devising interesting tunings – and had also learned how to write much better songs. But they applied a unique and utterly uncompromising vision to both skills, and were soon to use all of it to produce their greatest album, EVOL."

As Azerrad and Ranaldo suggest, it was around this time that Sonic Youth really began to flourish, not just with their songs and their sounds, but with their use of instruments – arguably demolishing the accepted conventions of rock music in the process. They began to revolutionise the use of the guitar, using individual instruments for specific songs in order to achieve certain specific sounds.

In one of the photographs taken at the show and included in the artwork for Smart Bar Chicago 1985 (see head of feature), Lee Ranaldo is holding an acoustic guitar. However, if you listen to the recording, it’s practically impossible to detect the woody resonance typically associated with the instrument. "It was a featured instrument on the song ‘Ghost Bitch’," explains Ranaldo. "All the droney feedback wails you hear in that song are my acoustic. It was the only song we ever used an acoustic guitar on back then."

This approach would become even more elaborate in the ensuing years of SY’s career. In the documentary 20 Years Of Sonic Youth, Moore speaks of the group having their equipment stolen. "We’d always been sort of known for using really sort of hot-rodded and unorthodox equipment that we would change and make into our own. You lose a certain guitar and you’d lose a song, because that song was based so much on that guitar, which would maybe only hold three strings, and was all held together with nuts and bolts."

"We liked the idea that different guitars had different personalities that you could learn how to utilise," elaborates Ranaldo. "One was for banging, one was for screwdriver, one was for beautiful chords."

So this period found the band taking a completely omnipresent tool and start making it entirely their own. They created a sound that, when surging through amplification, could only ever unmistakably be Sonic Youth, but they also deconstructed the instrument physically: re-tuning it, re-building it, jamming screwdrivers and drills in there, thrusting it headlong into a tsunami of feedback, and in the process often masking the fact that it was a guitar at all. This is the beautiful paradox of Sonic Youth: making their instruments sound like everything that a guitar ought to be capable of creating, while simultaneously using them in such a way that they’re almost unrecognisable as being guitars.

Ranaldo further explained these intentions in a 1985 interview with Melody Maker. "Our idea is that the instrument is not the guitar, as much as it’s the chain… It’s the guitar, the chord and the amp with the electricity pummelling through. The instrument doesn’t end where the guitar meets the wire. It starts where the sound comes out of the speaker. We like to imagine that we play our amplifiers."

The release of the Smart Bar recording, Ranaldo says, is only the beginning of a larger scale plan. "We have tons of tapes, we have been in the process of digitising everything for the last few years and creating a major database as well – it’s been a daunting task but [it’s] coming along," he reveals. "We had always thought it would be a cool idea to release live versions of the songs from various periods, especially as our songs mutated so much and really found their final ‘form’ by being played live once we were done recording the records – which to me function more like snapshots of what the songs later became in live performance."

He elaborates: "The idea to present a definitive Daydream live set, or Washing Machine-era live set or NYC Ghosts & Flowers, or Sister, The Eternal etc, seems pretty cool to us. So this set is hopefully the first of many such archival releases."

Aaron Mullan (of Tall Firs and Michael Rother’s Hallogallo), who worked on mastering the record, explains the choice for working with the Smart Bar tape as a jumping-off point. "The ideal archival offering would meet a list of criteria – it should be an unreleased and sonically compelling recording of an amazing performance, which not only sheds some light on the known Sonic Youth catalogue for the serious aficionado, but also capture the attention of the general fan. It’s a pretty tall order, but I think this tape from Chicago 1985 fits the bill."

Big Black were also in attendance at the show. I track down bassist Dave Reilly via his website WorthlessCripple.com, a site in which – up until a few years ago – he documented his life and the after-effects of a stroke he suffered in 1993. His response was a simple one: "I don’t care to participate, but genuinely wish you the best."

Guitarist Santiago Durango, meanwhile, is now a full-time lawyer. After attempting to chase him up by sending blind requests to various Chicago-based law practices and websites, I eventually received an email from him entitled "You looking’ for me?" I tentatively opened it only to find a charming response. "I would like to help you but unfortunately I have no recollection of that particular show." However, he did give great insight into the feeling of a 1980s SY show: "Given Sonic Youth’s unforgiving attack on the senses, and everything that is sweet and good about civilized society, it is likely my mind has repressed this memory in self-preservation".

Also along for the ride that night were Ed Roeser and Nash Kato of Urge Overkill. Kato recalls the evening with vigour. "Although my long term memory of live shows overall has been sadly compromised through the years, due in part to having seen/played so many myself, while enduring their invariable post game consequence, my recollection of this particular concert remains shockingly vivid."

At this point, Sonic Youth were still some way off hitting the big-time, signing to a major and arguably being in part responsible for inspiring the subsequent grunge boom. Ranaldo looks back fondly at the calm before the storm. "We were living the dream, as they say, five sweaty kids on tour all piled into a van, getting to play our freaky music across the country and in Europe, and turning on audiences to what we were doing everywhere we went – it was awesome."

For a group just as notorious for being voracious consumers of music as creators, Ranaldo recalls what they were listening to around this period. "We have the movie from the next year, our long-unreleased EVOL tour film with lots of shots in the van of us listening to music – everything from US hardcore to vintage rock and AM radio hits of our youth, to [Einstürzende] Neubauten to avant-garde and free jazz… and the rise of the still-fledgling MTV generation of artists: Madonna, Prince, Springsteen, etc." He adds that the MTV hits of the day played a particular role in SY’s gigs around this time. "The only thing missing from this recording is some of the between song tapes we’d play of other people’s music (like Madonna, Pat Benatar etc), which to us was an integral part of the set – this "quoting" of other current music of the day that we enjoyed – but those had to be removed for copyright reasons, unfortunately."

Steve Shelley remembers the night in question in an initially unflattering light, saying there was a "sparse audience, basement venue, [and we were] struggling with the house soundmen". (<a href="http://www.sonicyouth.com/mustang/cc/081185.html" target-"out">Click here for more on the band’s battles with bewildered sound guys.) Ranaldo too recalls the "low ceilings and grungy club vibe, it was pretty cool. Ceilings were kinda low and claustrophobic." He seems animated when recalling the intimacy and primal sense of the unknown that playing to small, often unknowing, unreceptive audiences could bring. "It was amazing! The style we were putting forth was kinda unknown outside of NYC, the extremism and altered tunings, etc. All stuff that was somewhat taken as the norm in NYC, but which the rest of the country and Europe, as we started going there before many of our peers in 1983, were unused to hearing."

It seems that it often took a while for people to ‘get’ what the group were doing at this stage. "Yeah, it was sometimes hard for the sound guys to get the idea of how ferocious we wanted it to sound," agrees Ranaldo. "They would always go for the ‘turn down the guitar amps so we can hear the vocals’ approach – they didn’t realise that we were shooting for the guitars to be roaring AND the vocals audible! Sometimes easier said than done. It took, really, having our own soundman, which we did from pretty early on, before we could avoid such lengthy discussions."

This ferocity rages like a backdraft throughout Smart Bar Chicago 1985. The shrieking couplet of ‘Brother James’ into ‘Kill Yr Idols’ is one of the album’s most hell-bent, headbutt violent moments, and according to Nash of Urge Overkill, its effects were truly felt that night. "In 1985, UO had just recorded its debut EP for Albini’s nascent label [Ruthless], as he was introducing us not only to the day’s brave new musical underworld, but to the actual bands themselves (whom he’d inevitably host/board upon their thrifty blaze through town)," he remembers. "And, it being late summer, such ceremony typically included a grilling by the lake, where we found these [decidedly coastal] minstrels to be as warm and congenial as they appeared ‘youthful’. So much so that we were simply nonplussed when, later that night, these very same New York punks proceeded to unleash the loudest, ‘wrongest’, cave-bound sensurround we [in Chicago] had ever heard! Here Ed [Roeser, Urge Overkill vocalist] and I had been sounding inadvertently cacophonous (despite our feeble attempts to play ‘correctly’) while THESE muthafuckers were redefining dissonance itself, yet with seeming deliberation. And blasting Madonna through Grand Master’s own boombox [this was the ‘encore’] left us ALL bowing before some morbid NYC sacrificial lamb. Perhaps nobody at the time may have imagined they’d just bore witness to any sheer rock LEGACY being forged (but it sure fucking FELT like it)."

Aaron Mullan shares Nash’s memories of SY’s deliberate dissonance. "[The] sheets of feedback insanity on [Bad Moon Rising], which I always assumed to be lucky studio accidents, turned out to be actual parts that Lee and Thurston could re-create at will."

This blurring of the lines is something that Moore himself once related to internally as well as externally. "Most people can’t tell now who wrote what," he told Spike Magazine in 2000. "I like that blurring of identities within the band because it becomes a unified thing that can’t be related to other forms of historical poetry."

Ranaldo backs this up. "Half of what we were perfecting at this stage was a ‘string theory’ that allowed the three of us to play in such a way that the sound was taken as a whole, and it often was impossible to tell who was doing what, and that’s how we liked it to be."

The guitar interplay on Smart Bar Chicago 1985 sparks like electricity from frayed wires. The electricity metaphor is a particularly apt one: the sound might feel wild, untamed and ragged, but it’s also incredibly fluid, its dynamics flowing, pulsing and surging. The guitars orbit one another; there is no lead and no rhythm, just two (and often three) feedbacking monsters shrieking and roaring in a blistering union of pain and pleasure. The collective effect is fractured and jagged, yet humming and glowing, striking a keen balance between the rough and the smooth.

In 1985 Ranaldo told Melody Maker that "we’re interested in the possibilities for sound making output from the guitar, bass and drums in ways that haven’t been [as] fully explored as we’d like [them to be]. We’re interested in textural sounds and the blending of instruments in ways that don’t fit into the standard lead and rhythm guitars and rhythm section backing it up."

Present on the recording in between those sheets of glacier-cold and blast furnace-hot noise is Kim Gordon, whose voice – like the guitars – marries coarse fierceness with quiet restraint. Gordon’s vocals are visceral to intensifying degrees. At times she howls with a demented, petrol gargling yelp, at others her voice just hums and slightly strains, adding depth and texture to the already wildly fluctuating sounds pouring forth from the stage. On ‘Intro/Brave Men Run’ her vocals sound like the howling cries of a shattered soon-to-be-fan, Kurt Cobain. And on the closing ‘Making The Nature Scene’, her voice and bass merge, spitting with a bubbling intensity, firing and sparking like a juddering car engine about to explode and die.

I ask Ranaldo about his thoughts on the show as a whole. "They were pretty much all really killer shows back then," he laughs.

This recording captures something perhaps not so commonly associated with Sonic Youth gigs of recent years: intimacy. It evokes a palpable sense of place and time; beer bottles clatter, clink and smash throughout, people openly talk, and you can practically smell the fug of stagnant sweat, beer and cigarette smoke hanging in the air. There is a loose, sparse quality to the atmosphere of the recording; this isn’t a swelling, bursting, sold out show, it’s a scattered handful of people in a basement on a Sunday night in Chicago. This is something that clearly appealed to Aaron Mullan when working on the record. "There’s also one other aspect of this recording I particularly enjoy: the crowd talking picked up by the room mic. It reminds me of the Velvet Underground’s Live At Max’s Kansas City LP. I really like two laments heard right before ‘Expressway…’ – "Will somebody buy me a beer?" and "I wanna dance!" There is something poetic about the contrast of these everyday complaints with the ferocious and otherworldly performance the complainers are witnessing."

Listening to the Smart Bar recording and experiencing the group at this crucial stage in their career could take you along one of two routes. It could act as a means to help fill the Sonic Youth shaped hole that their current hiatus has left behind. Or it could, perhaps, serve to widen it, sparking the realisation that the cacophonic pop of one of New York City’s greatest exports might never again be heard surging through the air. On the future of the group, both guitarist and drummer remain unclear. Asked if he knows of plans for the future, Ranaldo’s response is a simple "Nope", and Shelley’s is similar. "Well, as mentioned, lots and lots of work on reissues and recordings and video that already exists," he says. "Other than that, I don’t know."