In his 2011 book Sonic Persuasion: Reading Sound in the Recorded Age, Greg Goodale argues that sound can be read. That is, that it’s possible to critically interrogate and analyse recorded sound to understand a cultural moment. For example, he argues that in twentieth century music it’s possible to see, or indeed, hear, an attempt to acclimatise to the ear-shock of modernity.

“By turning penetrating noises into enveloping music, composers, performers, and radio engineers encouraged listeners to internalize modernity and find comfort in what had once been perceived as shattering sounds,” he writes. And this isn’t something limited to avant-garde composers – he highlights it in popular music, a compelling example being the use of locomotive rhythms in early music.

Síntomas De Techno: Underground Electronic Waves From Peru (1985-1991), curated and compiled by Buh Records founder Luis Alvarado, brings together tracks from underground electronic groups and solo artists operating in Lima in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. It ranges from melodic, if minimal, electro pop to more abstract industrial territory. Through it, we get a Casio keyboard-powered document of the time and place which widens the narrative of electronic music beyond North America and Western Europe.

It doesn’t tell a music writer sitting in London in 2022 what it was like to live in Peru 30 years ago, but, following Goodale’s reasoning, by listening to it we can get a window into how a group of people faced their reality, reacted to their situation, and made a mark on the world they found themselves in.

The 1980s and early 1990s were tumultuous in Peru, the country ravaged by a civil war between the Maoist Shining Path militants and the state. As Shane Greene writes in a 2012 article on Lima’s ‘80s and ‘90s punk scene for Maximum RockNRoll: “By the time the late 1980s came around, life in Lima was characterized by military lockdowns at night, black outs, car bombs, targeted assassinations and the radicalization of certain sectors of the urban poor and those young idealistic Peruvians hopeful for an overthrow of corrupt capitalist state system.”

In terms of music scenes, a loosening of import restrictions had allowed synthesisers and drum machines to trickle into and start shaping the mainstream at the start of the 80s. This manifested in disco influenced music, but an underground more focused on post-punk and new wave soon followed, formed around handful of pivotal nightclubs in Lima, such as No Disco, Biz Pix, No Helden and Nirvana.

This overlapped with ‘rock subterráneo’, (rock underground) a DIY punk movement originating in the mid-80s, documented in demos and zines lead by bands such as Narcosis, Leuzemia and Autopsia. The compilation captures the convergence of these worlds, pulling together electronic projects of some artists associated with rock subterráneo, as well as artists from outside that punk milieu.

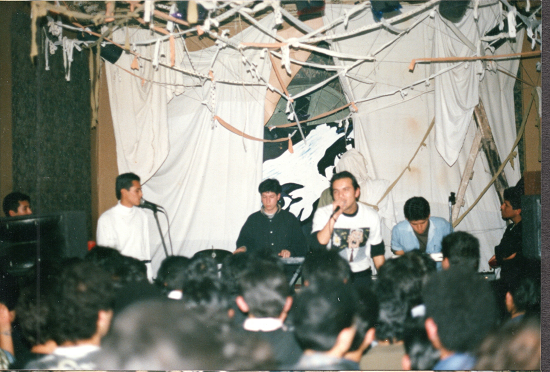

TdeCobre Photo by Oswaldo La Torre

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the compilation starts with a bang and a clang on Disidentes’ track ‘Martilio’. A sparse drum machine and keyboard groove is propelled into cacophony as metal plates and cylinders are bashed and rattled in a heady counter-rhythm underneath vocalist Martín Ponce barking out vocals through a megaphone.

Live, the group, Rodrigo Vivar (keyboard), Raúl Mondragón (percussion and vocals), and Hoover (percussion) joining Ponce, would perform in front of a slide show of the mothers of people who had gone missing in the violence which had engulfed Peru, contrasted with audio recordings of promises made by Peru’s then-minister of the economy. Although the recording can’t capture the group’s full multimedia impact, the intensity is there. The confrontation through sound, the group’s attempt to capture and respond with audio to the reality unfolding around them.

Elsewhere, you can hear Peru’s punks branching out and exploring what’s possible with drum machines and keyboards. Narcosis, in particular, cast a long shadow over the compilation. Active for barely a year in the mid-80’s, the group released the first fully DIY album in Peru, ‘Primera Dosis’, recorded with a Sony Walkman and a Dictaphone. This DIY recording spirit is present in a bunch of the tracks here, while all three members of the band appear in this compilation.

‘X2’ by Paisaje Electrónico, the solo project of Narcosis guitarist Fernando “Cachorro” Vial, was made using nothing more than the sounds of a Casio keyboard. The result is a shuffling instrumental, keys meandering along to create something surprisingly elegant from the Casio’s tones. Meine Katze und Ich meanwhile, is the project of Narcosis’ singer Wicho Garcia. The track here takes keyboards and drum machine in another direction, an angst ridden electro-punk song with lightspeed hi-hats and fierce drum breakdowns sounding like they’re trying to rip up the present and lob it into the future.

Then there’s El Sueño De Alí, a project involving Narcosis’ drummer Pelo Madueño. Their shimmering synth pop on ‘A donde’ is among the most colourful tracks on the compilation. Synthetic strings capture the electro-melancholy that ties Reproduction era Human League to Trans-Europe Express era Kraftwek. Underneath come dramatic jumps from ‘Autobahn’ elegance into bouncy synth breakdowns and, most surprisingly, a ‘Boys Of Summer’-esque guitar noodle. Like so much of this compilation, it captures the act of exploration in flight. Testing the boundaries of what can be squeezed into a pop song.

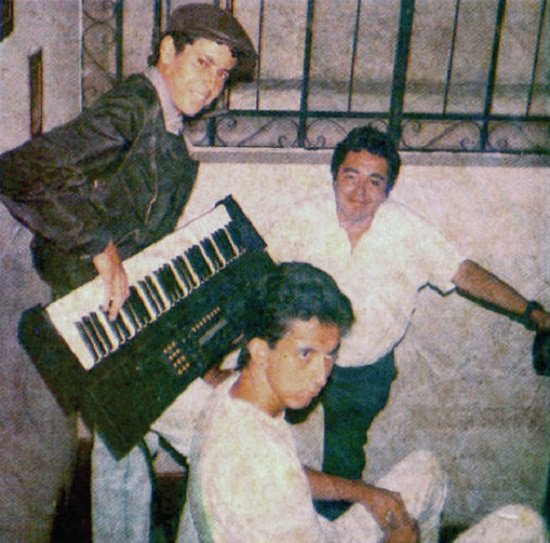

Fernando Cachorro Vial of Paisaje Electronico and Wicho García of Meine Katze Und Ich, photo by Rocío Morales

It’s important to stress not all these artists were involved in rock subterráneo. Meanwhile, as Greene’s articles explain in depth, the Peruvian underground had a complicated relationship with the country’s political upheaval: “There was never a simple overlap between the underground music scene and Peru’s revolutionary organizations. Inevitably some punks did not get involved in militant politics. Other, true to their anarchist orientations, refused to accept the incredibly hierarchal party structure and militaristic model that the Shining Path and the MRTA (a much smaller guerilla group) proposed as political alternatives.”

To some extent that comes through in the diversity of sounds here. Much of the first side of the compilation is dominated by brittle electronics and austere drum machines which feel rooted in punk. It seems to rage against the world. If you’re into anything from Suicide to Cabaret Voltaire’s ‘Nag Nag Nag’, you’ll find a lot to love here. ‘No Nunca,’ by T de Cobre, another Ponce fronted project, with its serrated synth and pounding drums a particularly caustic highlight.

Richer, poppier terrain surfaces on the second side, although it remains bathed in angst. It reaches a beautiful climax with Reacción’s ‘Y de aquí no me voy’. Almost gothic sounding in the way it blends the morose into the triumphant, intricate layers of sequencers dance through a soaring vocal performance from Támer Flores. Elsewhere, Ensamble twist orchestral hits into burbling arpeggios on ‘Industria de odio’. It achieves a ragged burst of agitation, part-industrial, part minimal synth pop. What’s ever-present in the compilation is a burst of twitching, claustrophobic energy in even the prettiest moments.

Speaking to Deep House Amsterdam, Daniel Miller, founder of Mute Records and, as ‘The Normal’, an innovator in electronic pop music in the UK with his single ‘Warm Leatherette’, said: “In the mid ‘70s synthesisers were hugely expensive and out of reach to many but when Korg and Roland synths came on the scene, it made a huge difference and had a liberating effect for those wanting to make electronic music. Everyone was inspiring everyone else. I released my single, the Human League came out a week later with theirs, then you had Cabaret Voltaire, Throbbing Gristle, OMD, Soft Cell, Depeche Mode all working in a short space of time. It was a wave of music.”

Daniel Bressanutti, from Belgium EBM innovators Front 242, has made a similar point speaking to Red Bull Music Academy about the impact of the tools of electronic music becoming more widely available, and more affordable. “When you are in the early ‘80s and have these new machines coming in front of you, and you’re living in Brussels, you don’t have the same feeling as a guy living in New York or a guy living in Kingston. You have a new machine, a new concept, you can start from scratch.”

Síntomas De Techno documents a similar surge of creative energy. Although synthesisers and drum machines had been trickling into Peru since the ‘80s after a switch in government had opened up the country to imports, the compilation has been expertly curated to capture what happened when they entered the DIY community. Looking at the credits, those synths tended to be Casios and Yamahas rather than Rolands and Korgs, but the restless deluge of innovation through more accessibility to technology they triggered resonates with the kind of milieu Bressanutti and Miller are talking about.

This point, about technology, affordability and availability converging to open doors to creativity, helps explain what makes Sintomas De Techno so fascinating. It scratches an itch in the same way that makes John Bender’s proto synth-pop experiments so enthralling, Warm Leatherette still seem so vital, and The Human League’s ‘Being Boiled’ as intriguing as ‘Don’t You Want Me.’ I don’t think it’s something as simple as retro or lower-fidelity fetishization.

Listening to Síntomas De Techno, you hear what happens when a creative group of people explore new tools for expressing themselves. You hear the excitement of possibility, of experimentation in flight, before the rule book had fully taken shape on how these machines should be used. It’s the sound of potentials being tested rather than mastered, and it’s addictive to listen to.

It’s important to stress these tracks are not just pastiches of what was happening in Europe and North America. If anything, the points when the tracks do sound reminiscent actually make the feeling of experimentation more acute. The songs on Síntomas De Techno play with structure and texture in a way far more nuanced than what was happening in the US and UK at the time, whether the endlessly snaking synths on ‘En la tiniebla’, by Cuerpos del Deseo, or Reacción’s urgent dream pop.

Reacción

At the same time, all of the tracks on Síntomas de techno seem propelled by an urgency seldom seen when synth pop and techno became more polished. The track from Disidentes or Círculo Interior’s ‘Primera secuencia’ have a mangled volatility which doesn’t sound like anything else I’ve heard from this period. In other words, the compilation opens up the narrative of electronic pop music, showing a world where industrial and poppier sounds didn’t get completely ghettoised from each other. It points to an ongoing wave of experimentation going on outside of the global north. While ideas of what electronic pop should sound like had perhaps started to solidify in the UK and US in the late 80s and early 90’s as bands like Depeche Mode and Pet Shop Boys started to achieve chart success, this compilation shows the open-ended exploration with synthesizers and songs carried on elsewhere.

According to the liner notes these groups were responsible for introducing styles such as techno-pop, EBM and industrial to Peru. Those descriptors make sense, and are useful for plotting the coordinates of what this compilation sounds like. But it’s important not to confuse the map with the terrain. Síntomas de techno is so effective because it captures something in between those genres. A flurry of open-ended exploration with new technology. In other words, the synthesizers these artists used were imported, but their ideas weren’t.

It doesn’t tell us what it was like to live in Peru in the 80’s and 90’s, but does give us a lens into a vibrant, fertile time of exploration, where artists seized newly available technology and tested the limits of what they could say with it. Grabbing opportunities to innovate in even the most challenging of contexts.