When I was a young girl, people approaching a century seemed like creatures of mythology. But age creeps up, then explodes in midlife. You realise insane things, like that the end of the Second World War was as close to the release of Kate Bush’s Hounds Of Love as you are to it now. Each season speeds past in time-lapse. History shrinks. Long lives contract.

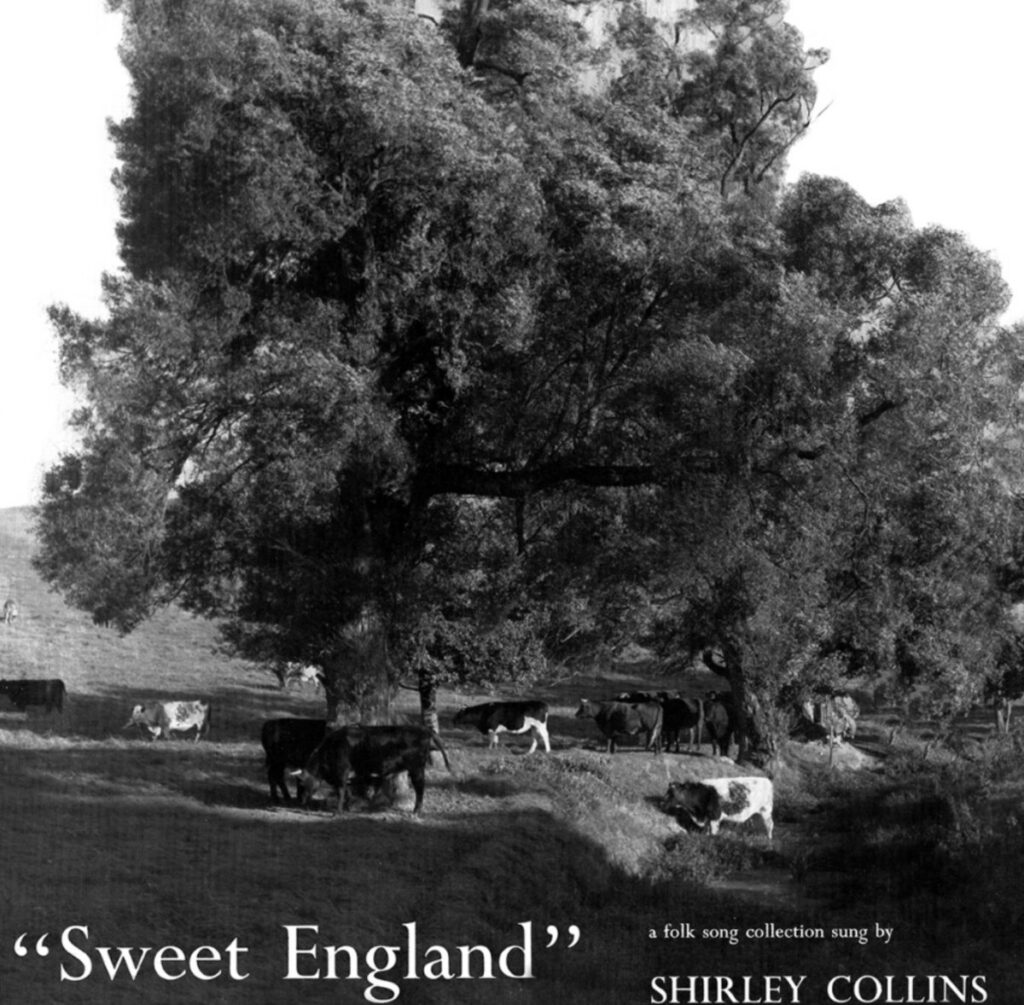

On 5 July, Shirley Collins will turn ninety, a woman I’ve known through interviews and friendship for seventeen years. A limited vinyl edition of her debut album, Sweet England, with its original black-and-white bucolic artwork and liner notes by Alan Lomax, has been remastered to mark this occasion. (Released by a label local to her in Lewes, called Moved By Sound, their roster of reissues includes jazz poet Jeanne Lee’s Conspiracy and Estonian psych-folk singer Reet Hendrikson’s stunning Reet).

It was recorded when Collins was 22. These 19 tracks were part of a two-day, 37-song session recorded by folklorist Peter Kennedy in his tiny home studio, with just a few musicians supporting her. They were an interesting bunch. The atomic physicist and radar pioneer John Hasted, an important figure in the early days of skiffle, played banjo. And then there were American guitarists Guy Carawan, the man who introduced Pete Seeger’s ‘We Shall Overcome’ to the American Civil Rights Movement, and Ralph Rinzler, later a Smithsonian Institute curator and Grammy Award-winning producer.

Lomax begins his notes by introducing “perhaps the most elusive of sounds… the voice of a young woman, alone in the kitchen or garden, singing an old song”, the domestic setting of his description full of the expectations of the era. Usually, when “the microphone appears, the magic vanishes”, he adds – Collins is the exception. In her, he concludes, “is the wistful and tender magic of the young girl, that is beyond art.”

This description is romantic but reductive. It doesn’t sum up the impact of hearing Shirley’s first outing on record, her voice all airy, open-hearted and new. She sings directly and confidently often, the naive edges of her voice not disguising her clear-headed maturity. In the murder ballad, ‘Omie Wise’, she tells us, damn straight, about a deluded woman killed by her lover, a man who later “broke jail, into the army he did go”. ‘Pretty Saro’ is sung a cappella in devastatingly bleak, broken tones (she’d later revisit this on a more mystical version on 1965’s Folk Roots, New Routes, announced by Davy Graham’s ringing, high guitar harmonics, lashed with raga-like flourishes and reverb).

Collins’ 1958 accent also carries a little polish of the Queen’s English, unsurprisingly for a time when received pronunciation was the voice of the establishment and education. “You can hear the Sussex accent that my headmistress was trying to make me lose”, Collins said of her performance of ‘Turpin Hero’ to me, for this site in 2023. “Thankfully, I didn’t quite make it.”

Alongside this ballad she learned in school, she sings songs she learned from albums for children, including the frankly bizarre ‘Lady And The Swine’, a love song replete with oinks. Others come from her family: ‘The Cuckoo’ – a sweet tribute to a bird that announces springtime – from her great-grandmother; Hebridean ballad ‘Hori-Horo’ from her uncle George, taught to him by a New Zealand soldier during the Second World War Desert Campaign in North Africa, which he later sung annually at the Collins’ family’s Boxing Day parties.

His niece hits the high, sensual notes and lower, resigned tones of ‘Hori-Horo’ with conviction. She’s also gorgeously no-nonsense on ‘Bonny Irish Boy’, a love song she learned, intriguingly, from an Irish bus conductor. You get the sense of a young woman eager to get down all the songs she’s learned and loved, just as she knows Lomax does with musicians in the field – something she’d experience first-hand a year later in 1959, on her famous trip to America to join him collecting songs in the South.

Collins’ facility as an arranger and composer – the latter a title not often given to her – is also vividly clear from day one. In her arrangement of ‘Sweet William’, her banjo acts like a rhythm guitar, while a low guitar solo fights through the thickets of sound – imagine a trad. arr. equivalent of Peter Hook’s chiming bass for Joy Division and New Order. Collins was new to the banjo at the time, an instrument which Gramophone Magazine’s critic sniffed at in a 1960 review of the album (“purists may object”), but her playing reflected the Appalachian music she adored, as played by heroes like Jean Ritchie. Collins revealed early on how traditional songs crash and lull across the Atlantic and back again, their edges altered in fascinating ways.

Her real genius – on all levels – comes in ‘The Cherry Tree Carol’, a deeply eerie version of the Nativity story in which Joseph, “an old man”, marries Mary, “the Queen of Galilee”. Collins wrote the lucid lamenting melody for words that had existed since the Feast of Corpus Christi in the early 15th century.

She first performed the song live on Lomax’s 1957 Christmas Day BBC radio special (released by Rounder Records in 2000 and available on streaming services). She acts as its omniscient narrator, telling us of Mary asking Joseph to pick her cherries, before he accuses her of infidelity. Her unborn baby then speaks, commanding the cherry trees to bend down to her. Mary’s character fizzes and flashes in Collins’ vocals. A sacred woman spectacularly rises in sound.

Collins’ signature song, to my mind, ‘Hares On The Mountains’, is also first performed on this album, her young voice “frisking and fooling” against rollicking banjos in a bouncy, major-key setting. Switched to the minor, the song takes on a deeper, erotic charge in Collins’ 1965 version with Davy Graham on Folk Roots, New Routes, and bears a solemn magic on 2023’s Archangel Hill.

This last album also features another of Sweet England’s songs, ‘The Bonny Labouring Boy’, originally sung to her and her sister Dolly in air raid shelters by their grandfather during the Second World War to give them comfort and peace. Collins sang it again in the 1979 National Theatre play Lark Rise, as a video on YouTube still shows us, when she started suffering from dysphonia after a traumatic breakdown of her marriage – a condition that would leave her silent for the next thirty-five years.

In 1958, she sang it high, her speed slow, like a girl savouring every long day of “the blooming Spring”. In 2023, she’s a lot lower but faster, as if eager to remember how it felt to rove out one May morning.

Collins spends most of her days now in her cottage in Lewes. She emailed me yesterday to confirm a few details about the album, as full of spirit as ever (“JOHN HASTED PROVIDED THE OINKS!”). Her beloved local Morris men will dance outside her house, as they have done now for many years, to celebrate her birthday. Her early recordings still throb with blood, breath and life. Sixty-seven years is nothing at all.