Alaska, so the cliché goes, is populated by those who have fled somewhere else, something they’ve experienced, something they’ve done. Why else would you go to somewhere so remote other than to lose yourself or re-emerge as someone else? The view of a frontier state populated by lost souls, people with histories, predators even, is no doubt the product of crime novels and half-remembered serial killer statistics, as well as the feeling that hard places make hard people. There might even be a more superstitious suspicion that the feral wilds can somehow seep into a person. There are plenty of peaceful resilient communities living in Alaska to refute these stereotypes and projections. Yet just because something is a cliche doesn’t mean it isn’t true now and then. At the very least, you go to edgelands with intent, hidden or otherwise.

The name Katmai National Park And Preserve implies a mastery over the landscape, a containment of the wilds. In reality, it is an untamed place of sleeping volcanoes, glaciers and earthquakes, caribou and wolves, a place visited by floatplanes piloted by grizzled veterans. There is astonishing beauty to be found there, in the serene desolation of the Valley Of Ten Thousand Smokes for instance, but it is wise to treat such places not as a romanticised Arcadia but as Hobbesian in nature, places where, if too starry-eyed, human lives might well be rendered ‘nasty, brutish, and short.’ Inevitably though, from a culture weaned on too much Disney and not enough Darwin, the starry-eyed do emerge and somehow make it there to the end of the line.

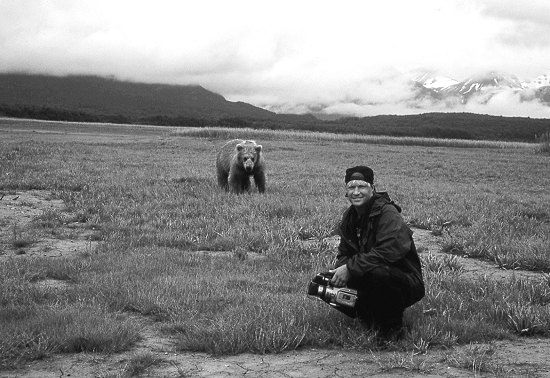

Timothy Treadwell was one such traveller. He had come to be at one with the animals, namely the bears who feast, or starve, at the salmon runs. Treadwell gave them names and tried playing with them and their cubs. The sixty or seventy stone fiercely protective bears, that is, all claws and incisors. How Treadwell survived as many years as he did is interesting in itself but die he did, and horribly so. He left behind hours of footage from which Werner Herzog (a lifelong explorer of explorers) created the exceptional documentary Grizzly Man.

The film is, in its peculiar way, the negative image of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea Of Fog with Treadwell being an anti-hero not in the Jacobean or noir sense but in the way he inadvertently and clumsily manages to dismantle the idea of heroism while simultaneously being suicidally brave: pitched in the middle of a bear trail maze, with no bear spray, gun or electric fences, and warned repeatedly by the park service who tried to save him from himself. In the footage, Treadwell is infuriating and yet compelling, deeply tragic and deeply cringeworthy. You feel for the guy despite yourself, a tension that makes the documentary riveting. Treadwell seems a product of both his background and his culture. He hides his childhood trauma and propensity for excess beneath an infantilised exterior — a grown man who carries around a teddy bear and is given to chanting "I’m in love with my animal friends" — and a new identity, Timothy Dexter becoming Timothy Treadwell, just as Christopher McCandless tried to ‘become’ Alexander Supertramp. Treadwell was lured initially to California, that other frontier, where he could reinvent himself and satiate his delusions, and no doubt be fed upon in turn, as many have before and since. He survived the resulting overdose (after he failed to be cast as Woody in Cheers) and found his meaning in raising awareness for the ‘protection’ of bears. His annual summer trips to Alaska, over thirteen years, were the most remarkable of Treadwell’s life and yet they were also a kind of latency period on a path of self-destruction.

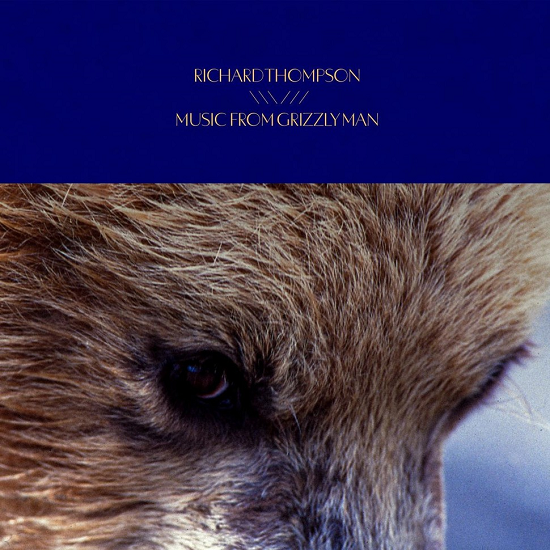

Though it should make us wonder how manmade our view of nature is and how armourless that leaves us, Grizzly Man is not just a moralist cautionary tale about the dangers of anthropomorphic sentimentality. Herzog’s film has a tenderness to it. It’s reflective and meanders and a great deal of this is due to Richard Thompson’s soundtrack (to be reissued next month). Though his songwriting catalogue is astonishing and somewhat underrated (from the sublime early days of Fairport Convention to the stark, exquisite albums with Linda and beyond), Thompson is perhaps best known for his guitar work. Averse to the ‘white guy plays the blues’ model of the sixties (digging into "someone else’s roots" as Steve Winwood put it), Thompson chose another path, that of the roots music of this rain-lashed north Atlantic archipelago we find ourselves on. There’s something both earthy and maritime, deep and wide, about Thompson’s style. Medieval trills and Celtic reels merge into nimble Django-esque gypsy jazz picking, the simulated drone of bagpipes merge into the drones of Indian raga music. If you try playing along with Thompson, you soon find yourself lost. There is a mercurial quality, both traditional and innovative, and he shakes off any pursuit. As Ralph McTell put it, "When you’re a youngster you want to know how the magician does the tricks and when you’re mature, you don’t care as long as you can enjoy the magic. Richard’s way of playing the guitar… it’s as if he’s put his hand there for the first time and where will this go?"

In Grizzly Man, much of what Thompson has learned and created comes to the fore with a kind of weatherbeaten ease. At times, it feels almost like a Western soundtrack, one where the music of these islands meets the vast North American skies. For all his meticulous notes and explorations, Thompson has a superlative sense of space, knowing what to leave out as well as include. The music is evocative not only of the landscape but Treadwell’s psyche, a deceptively gentle river on the surface, hiding currents, whirls and debris that shadow the surface periodically. There is a homely feeling throughout, punctuated by sudden jarring trespass. Though his guitar style is all his own, it’s not a million miles from the atmospherics of Ry Cooder’s Paris, Texas or Neil Young’s Dead Man score. By improvising to a screening of the film, intentionally or not, Thompson embodies the only effective response we can have with nature, which is simply to respond to it, with due care and respect, otherwise we risk being consumed, individually or collectively, whether bear attacks or climate change.

‘Tim And The Beasts’ begins the album on a placid note, recalling the warm yet melancholy-tinged nostalgia of Mark Knopfler’s soundtracks. This bucolic mood continues in the playful ‘Foxes’ and the sleepy serenity of ‘Twilight Cowboy’. The interplay between musicians is gorgeous, at times telepathic (‘Parents’ being a fine example), and even when the vignettes are short (‘Bear Swim’ for example), they have an exquisite gentleness to them, like pastel sketches.

Shadows gather, though. ‘Glencoe’ has a pleasant rolling Victorian air but its title invariably points to undercurrents of betrayal, murder and how unforgiving the wilds are when circumstances turn. Aided by Jim O’Rourke, ‘The Kibosh’ has a touch of the otherworldly transformative quality of dusk, while ‘Ghosts in the Maze’ has spectral shiver to it, like the night-wind on your back as you bask in the glow of a campfire. The more clamorous ‘Grizzly Man (Main Theme)’ is full of echoes of Thompson’s past work (especially the classic Shoot Out The Lights and I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight) with that same feeling of how can music sound so raw and elegant at the same time, which is the definition of a certain type of pain. A similar kind of jagged sadness is evident in ‘Treadwell No More’ alongside a pulse like a ticking clock, as baleful a presence as that one bear that Treadwell continually felt uncomfortable about, rightfully as it turned out. While Grizzly Man lacks the choral weirdness of Popol Vuh and Herzog’s earlier soundtracks, despite experimental moments like ‘Big Racket’, its depths lie in texture, reverb and ultimately emotion. It perfectly mirrors the film, albeit with its own unique depths, like a reflection in a river.

And what of Treadwell? It’s easy to judge him but his sin — solipsism essentially — is a common and forgivable one. There’s a clip of Treadwell on Letterman where he’s asked, "Is it going to happen that one day we’re going to read a news article about you being eaten by one of these bears?" The audience launch into hysterics but significantly neither the talk show host or Treadwell laugh. In that moment, with his ridiculous He-Man haircut, Treadwell looks exactly like what he’d unknowingly become — a character in a Werner Herzog movie. Lost and absurd and as deserving of sympathy as Kaspar Hauser or Stroszek.

One look at the bears, by contrast, and you know they demand respect. Timothy Treadwell gave them something else, something unwelcome, complicating and dangerous. Treadwell gave them love and they tore him apart for it. The lesson in all of this, and it’s eternally prescient, is that there is a cost for departing from material reality, regardless of how benevolent your delusions appear to be. At some point, the deficit becomes unsustainable and reality notices you. Consider the contrast between the names Treadwell gave the bears – Tabitha, Cupcake, Melissa, Miss Chocolate – and the floatplane pilot arriving to find a bear feasting on a human ribcage.

The details of Treadwell’s demise are brutal but not illogical. He stayed on too long, too close to hibernation, around foul-tempered and desperate bears. He knew the dangers all along, admitting "There are times when my life is on the precipice of death," and "Once there is weakness, they will exploit it. They will take me out." Yet he fooled himself that he could impose his will, "But so far, I persevere. Persevere." In the process, once his perseverance and luck ran out, he showed both the limitations of mock-heroic Nietzschean Romanticism and infantilised Gaia-worship. His camcorder was left running with its lens cap on as he and his partner Amie Huguenard were eaten alive. In the audio, the rain can be heard on the tent with Amie screaming over and over to Treadwell, who is outside, "Play dead!" It tests one’s sympathy for Treadwell to know that, knowing himself that he was probably heading over the brink, he brought his rightly fearful girlfriend along, condemning her in the process. For all his Doolittle aspirations, he and Amie were the first people to die at the hands of bears in the national park. Treadwell also ultimately did little to protect his beloved bears, given two of them were shot after attacking responders. In environmental terms, his tale is one of the wisdom of leaving things the fuck alone.

Yet it is hard not to be moved by Herzog’s film, Thompson’s music, the bush pilot singing along to Don Edwards’ song of lost things ‘Coyotes’ and adding his own line ‘Treadwell no more.’ Herzog is acutely anti-sentimental, "And what haunts me, is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discover no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature." In stark contrast to Treadwell keening over a dead fox, Herzog claims, "I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility, and murder." Though a more steely and protective view than Treadwell’s, this too can be a distorting prism, for we do have kinship, understanding and mercy, despite everything. Herzog is right though that is mortally dangerous, however tempting, to try to exist solely within a fiction of ourselves and the world, and yet this temptation is a human one.

Seventeen years ago, I watched Grizzly Man with my late father. At the time, I judged Treadwell as a buffoon. I had a healthy grasp of the wilderness and my own limitations but nevertheless, since then, I found many excuses to stay on mountain peaks too long or ignore the times of tides or venture off the map at ungodly hours. I found the right stories to justify ignoring the weather turning. Born of chaos as much as nature, Treadwell sought kindness, benevolence, harmony in his life. His stories of the bears served a function for him. Maybe it eased the weight of existence. Listening again to Thompson’s soundtrack, I thought of my dad who’d rolled his eyes at Treadwell at that screening but was transfixed by the film anyways. My father was a gardener-groundsman for the council who laboured through all weathers. He was also a hippy, a Celtic one at that, whose head was full of stories of the sidh and the Green Man and will-o’-the-wisp and whatever, things that I had long mistaken for nonsense. I realise now it was a way of colouring a stark world and lightening the load of a life that could be brutal. Shaking his boots off, caked in clay, after a long day’s work, my father would occasionally talk of dank things – the sickly-sweet smell when finding decaying creatures, euthanising myxomatosis rabbits with the edges of shovels, watching pauper burials in the cemetery he tended. The kinder world of folklore was a respite, if not a refuge. The key was not to believe it, as Treadwell had. We are vulnerable when we depart from reality, most of all to our own weaknesses, and we are vulnerable when we fail to recognise that there are aspects to this world that we do not completely know or control. The wilds are a reminder that there are other forms of being. "Thank God for hard stones; thank God for hard facts; thank God for thorns and rocks and deserts and long years." GK Chesterton wrote in The Poet And The Lunatics, ‘At least I know now that I am not the best or strongest thing in the world. At least I know now that I have not dreamed of everything.’

The reissue of Music From Grizzly Man by Richard Thompson is out now via No Quarter