These days I hold out little hope that the barren dust bowl that is The Archive could still bear fruit worth eating. It has been overpopulated and overfarmed. So many reissues or ‘lost recordings’ drop like just more plastic pressed up to sell, cashing in on things nobody actually ever thought were any good in the first place, but which have been bestowed with the grace and gloss of time simply pushing inexorably onwards. Yet here I am, happily gorging on what might be one of the most essential live box sets now in my collection. I’ll go out on a limb and say that over the last few months, it has become as important to me as The Complete Matrix Tapes, because it fills in a huge part of the picture that was previously only sketched out. More than that, it shows what there is still to discover when a very good researcher asks the right people the right questions.

Snow Beneath The Belly Of A White Swan is a follow up of sorts to 2021’s Song of the Avatars: The Lost Master Tapes, and is sourced from the same suitcase of tapes that filmmaker Liam Barker tracked down while making his essential documentary on Basho, Voice of the Eagle. Barker says that during filming, he found out that Basho’s personal collection of his own master tapes had been bequeathed to a member of Sufism Reoriented following his untimely death after a chiropractic accident. From there they found their way to a follower of the movement’s founder, the Indian spiritual master Meher Baba, whom Barker was able to track down and who gave Barker access. The case was a holy grail, containing over 100 reel-to-reel tapes which have now been curated into two box sets: the 2021 studio set and now this collection of live recordings, some of which have vague provenance because of poor labelling, meaning that identifying dates and locations have often come down to deduction or guesswork.

What we do know is that Basho was a prolific performer, who nonetheless struggled to make any kind of living from his shows. He never had a manager, and cadged lifts to his own gigs, sometimes taking odd jobs to cover the rent. Robbie Dawson’s sleevenotes state that he was “not as employable nor as popular as his peers” and quotes from reviews that – quite perplexingly given the glorious flights taken on some of these recordings – criticise his inability to deliver the ‘soaring performances’ of peers John Fahey or Leo Kottke, and that he spent an ordinate amount of time tuning his instruments. The Chicago Tribune commented that he was “wholly too esoteric for most tastes and for his own good”, and Dawson writes that he sometimes tempered the spiritual and non-Western influences for live shows, after finding audiences reacted better to what he called the ‘cowboy trip’ and straighter Americana. That Tribune reviewer was out of their mind – I certainly hear some ‘soaring performances’ here. I have written before for this website about how when Basho reaches skyward it feels so raw it is like he has no skin. This is only intensified in moments of ‘bad’ recording on this release, as when ‘Himalayan Highlands’ slips into the red and begins to distort just as Basho’s impassioned vibrato is lifted on glittering clouds of strings. “I’ve heard things you wouldn’t believe up there in the great sky,” he told Frets magazine in 1981.

I often hear a rushing of energy in these recordings, where his playing flows like a fast and complex river, as in the title track or ‘The Golden Shamrock’ (the only recording of this piece). I listen with the same ears to the coursing waterways in Annea Lockwood’s river recordings, some deep and rolling, some quick and glittering, well suited to a shifting focus on narrow or wide-field listening.

The comparison made is always between Basho and the grumpy John Fahey – Erik Davis termed it well when he said Basho was “the mystic moon to John Fahey’s brash, strumming sun” and one of the things I took from Barker’s documentary is that while it seemed Fahey and Basho were never going to fully ‘get’ each other, being people with entirely different temperaments, that connection was crucial to understanding Basho, who is recorded here playing the languorous blues of ‘Some Summer Day’ and ‘Sligo River Blues’ by Fahey (and the rare track ‘Portrait Of Fahey As A Young Dragoon’). But where Fahey always seemed an obstinate kind of visionary, Basho loved to LARP, incorporating a bazaar of borrowed sounds, motifs, and tunings, and an odd, naive sort of presence.

It is these Bashovian idiosyncrasies that make me so enamoured with him, in ways I could never feel for Fahey, as much as I adore his music. It pains me to hear of Basho straightening out his sound for the Americana cowboy set, as much as I like that stuff, because I like it more when he is earnestly inhabiting various spiritualities; I like it when he gets on an overwrought mediaeval trip, and I have always liked the stage banter that slips out while he retunes his instruments. On the album Bonn Ist Supreme, one of the few live recordings released prior to this set, he says: “this guitar’s over a hundred years old… it’s a little fussy” in his Kermit sing-song way that pleases me greatly. Similarly, some of my favourite moments on this set include the moments he addresses the audience – the way he speaks is like a tumbling waterfall. “Those lights are funny, they smell. I can smell ’em,” he says on ‘Autumn Nocturne’, an odd thing to say, begging the question: of what?

When I first got into Basho he was in the canon, but as a weirdo and outsider – rumours about the way he lived and what he was like seemed intensified by his freak death at the age of 46 – but what I take from Barker’s biopic and these two box sets on Tompkins Square, is that Basho might just have had too many big real feelings for some of the scene he came from. Was he too theatrical? Too excitable? Too earnest? He studied and was swept up in esoterica and spirituality from various traditions, ready to try and nail the feeling of a raga, for example, if not the form. I love and envy that readiness to engage; the lack of self-consciousness that might be a cause for concern were he playing today. This box set has only increased my fondness for his playing, adding movement and colour to the portrait as it exists. It is a total wonder, and a nail in the coffin of my critical faculties when it comes to the music of Robbie Basho. My heart and not my head for Basho – my heart.

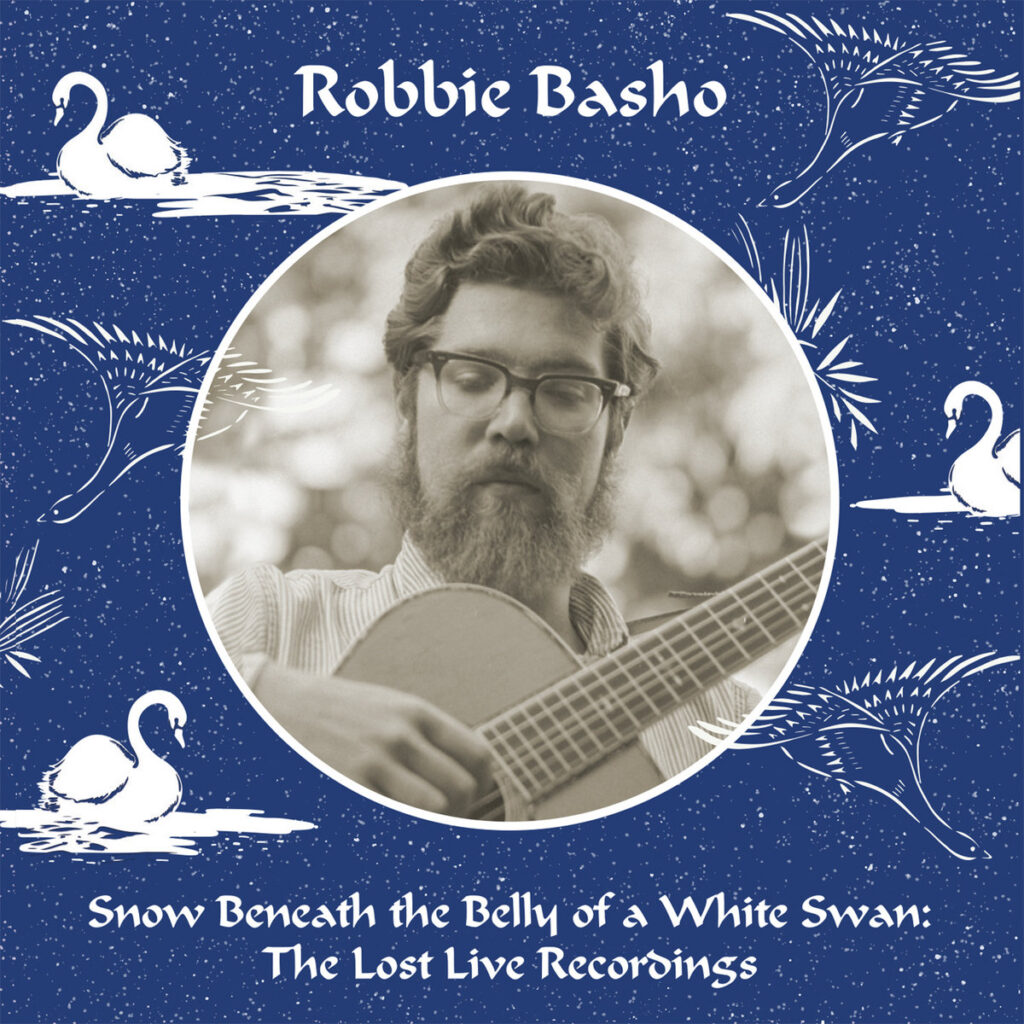

Snow Beneath The Belly Of A White Swan: The Lost Live Recordings by Robbie Basho is out now via Tompkins Square