Little about Pete Shelley’s solo career was conventional. Sky Yen, was technically his first solo album, in that it was an album and that the record’s sky blue, graph paper sleeve came emblazoned with his name, but it was actually recorded in March of 1974, a year before Shelley and Howard Devoto even decided to form a band. The record consists of two pieces, each twenty-minutes and forty-five seconds in length. It was performed on a purpose-built oscillator, the objective being to create a soundtrack for one of Devoto’s student films. Shelley reportedly used his own sweat to manipulate the circuitry.

Sky Yen owes a little to Shelley’s much proclaimed love of Can. There’s a bit of early-Kraftwerk in there alongside shades of John Cage. He said it was influenced by the Cluster and Tangerine Dream, groups he’d heard played by John Peel. It’s amateurish stuff, really. Few would have ever heard it if Shelley hadn’t decided to release it on his own, short lived Groovy Records in 1980. It was one of just a handful of releases that included the soundtrack LP Hangahar by Sally Timms and Lindsay Lee – on which Shelley makes a guest appearance – and an album called Free Agents by Eric Random, Francis Cookson and Barry Adamson. Sky Yen sold out of its original pressing of 1,000 but god knows what Buzzcocks fans thought of it.

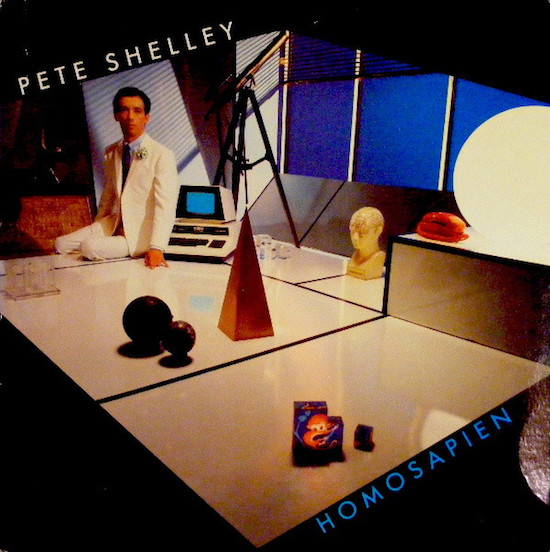

In reality, 1981’s Homosapien was Shelley’s first solo album proper, in that it was an album and that the record’s modernist sleeve (the musician sat amongst a statue of the Egyptian god Anubis, a Commodore PET computer, a red telephone, an erect telescope) came emblazoned not only with his name, but contained actual songs! Still, it’s most likely that Buzzcocks fans, drawn to the Bolton born band by their almost peerless run of perfect rapid-fire punk between 1977 and 1979, were again more confused – this time by ping pong drum machines and lusty electro pop – than they were enthralled by Shelley publicly exploring his growing interest in electronic music.

Again, the majority of Homosapien’s songs predate the Buzzcocks. Shelley had planned to mould the core of his band’s fourth album – the follow up to 1979’s uneven A Different Kind Of Tension – from this handful of songs that had been kicking around since his late teens. The band even rehearsed them and tried to lay them down with producer Martin Rushent in Manchester’s Pluto Studios. Yet this was a beleaguered Buzzcocks who had recorded and released three albums of exceptional quality within two years but were worn down by what they perceived as a lack of financial support from their label EMI.

Concerned that the sessions were proving unproductive, Rushent called time and suggested to Shelley he retreat to his newly built Genetic Sound studio at his home in Streatley, Berkshire. The songs created here would ultimately become a solo album. The Buzzcocks wouldn’t release another record for fourteen-years.

"’Homosapien’ was originally supposed to be a demo for a Buzzcocks track,” Shelley told Taylor Parkes in 2015. “But when we’d done it, Martin was sat there listening to it on repeat, as he often did, then suddenly he swung round in his chair and said ‘That’s finished, that is. You could release this as it is if you wanted’. So we went to Andrew Lauder, who’d been our A&R guy at United Artists and who was now at Island Records, to see whether we were mad or not. It was just two of us in a studio messing round with machines and stuff. I was writing computer programs where I’d tell it the notes I wanted it to play, and then it’d tell you the input you had to enter, all that stuff. We didn’t know if we were just fooling ourselves. Andrew Lauder heard it and said ‘Wow – are you doing any more of these?’”

Homosapien isn’t perfect; it’s far from his strongest work as a lyricist, many of the tracks feel more like sketches than they do fully worked out songs, it falls between two stools – exciting electro pop and listless twelve-string balladeering. “The problem is the bulk of the raw material is too ineffectual, often embarrassing and half realised, to give the songs a focal point which binds, injects or drives them with the necessary conviction or resolution” said the NME at the time, serving as, if nothing else, a reminder that what is revered about the golden age of music journalism rarely stacks up in the cold light of day. But it certainly has its moments; ‘Yesterday’s Not Here’ contains an atonal guitar solo that Blur’s Graham Coxon has almost certainly heard more than once, while Kim Wilde’s 1986 Supremes cover ‘You Keep Me Hangin’ On’, bears a certain similarity to ‘Guess I Must Have Been In Love With Myself’.

But in the title track, Homosapien contains a truly great song; four and a half minutes of bubbling synth and clever wordplay, atop which Shelley puts to one side the knowing coyness he’d frequently inserted into his contributions to the Buzzcocks catalogue, loosens his tie, and, as much as he ever committed to tape, is explicit in telling the listen exactly what he desires. “I’m the shy boy,” he stutters. “You’re the coy boy” before adding the couplet that would see the song, released as a single in advance of the albums release, banned by the BBC, contributing exponentially to the song missing out on the sort of classic eighties pop status awarded to, say, The Human League’s ‘Don’t You Want Me’ (incidentally, a song also recorded by Martin Rushent, as was the songs parent album, Dare).

While the single fared well in both Canada, Australia and New Zealand, cracking the top ten of the first two and narrowly missing out in the third, in Britain, the BBC regarded the line “homosuperior, in my interior” as an explicit reference to homosexual sex. Two years later they would ban Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s seminal ‘Relax’ for similar reasons, though they would ride the resulting controversy to the number one slot. It’s certainly exciting to hear the songwriter talk about desire so primally after previously only ever letting the listener in on whispers – empowering even – but it’s important that the central tenant of the song isn’t lost in a rush for classification. Shelley says as much in the climax of the piece, repeatedly gasping the words, “I don’t want to classify you, like an animal in the zoo”.

Peter Allen’s Bi-Coastal might have been released a whole year prior, as was Pete Townshend’s ‘Rough Boys’, but it would be a stretch to call those songs great or even pop songs. In that context ‘Homosapien’ is the eighties first great bisexual pop song. There is undoubtably great glee expressed by Shelley in the song that he’s found a connection with someone. We know it’s a he thanks to the dropping of the gender-neutral pronouns used throughout his songwriting for the Buzzcocks. The confidence he exhibits in knowing he’s found someone unashamedly on the level is endearing. But the “and the world is so wrong, that I hope that we’ll be strong enough, for we are on our own, and the only thing known is our love” is a line so tender, the song is surely as much about human sensuality as it is about who he’s shagging.

Shelley would never write as explicitly about his desire again. He’d also never write as beautifully about love. Despite several re-releases between then and now, this brilliant song lay tucked away on a flawed but interesting record for decades. It’s inclusion on the soundtrack to 2014’s Pride movie helped save it from obscurity. As did – as is the way with these sorts of things – the passing of its composer last week. It should never have been so. It should have been a song that defined an era. A queer anthem for the ages.

As we said on the way in, nothing the man did in his solo guise was in any way conventional.