The hilarious thing to do in schoolyards in Britain when ‘Homosapien’ came out in 1982 was to sing its title line as “you’re homosexual too”. Yet former Buzzcock Pete Shelley was way ahead of the mockers and rockers on this synth pop venture, ‘Homosapien’ being far queerer than playground masculinity patrollers – or the banning BBC – could imagine. It’s not just the lyric’s double entendre, “homo superior, in my interior” but the song’s expansion from the personal to the political: “I just hope and pray that the day of our love is at hand”. A love song hence becomes a demand for liberation, insisting that “homosapien” is the only label that matters: “I don’t want to classify you like an animal in the zoo”. But there was something equally queer about the sound of ‘Homosapien’, as trailer single for a synth-dominated album. With the era’s ‘rockists’ regarding synth pop as inauthentic and effeminate, this un-manning of music tracked Britain’s shift from a production to service economy, propelled by technology.

Now synths dominate popular music, it’s easy to forget synth pop was initially punk-adjacent, a materialisation not just of punk’s anti-muso ethos but its social transgression and its dialectic between futurism and dystopianism. While Homosapien was released in January 1982, it was recorded much earlier, as Shelley and Buzzcocks/Stranglers producer Martin Rushent tested out electronic equipment in the latter’s new Genetic studio, first as Buzzcocks demos, then prompting the Buzzcocks’ demise. You couldn’t get much more of a sign of the times. In fact, it was Homosapien that got Rushent the job with the languishing League, whose Dare – which came out first – would help to define the new course of pop music. Not only was Shelley further ahead of the curve than chronology reveals, but Homosapien is the anti-Dare, not so much “transitional” as Simon Reynolds argues, but an augur of an 80s that never transpired. Where Dare soared, Homosapien bombed. Buzzcocks had always been the poppiest of punks, but Homosapien eschews Dare’s populism, pursuing an arty anti-normativity and, paradoxically, a humanism absent from the actual 80s – there are few colder songs than ‘Don’t You Want Me’. It’s not just a matter of sentiments but sonics, with guitars warming the synths on Homosapien, a foot in the past that resists Dare’s technological chill.

All this is exemplified by ‘Yesterday’s Not Here’, which sets a brilliantly Beatlesy melody against blipping synths and jerky drum machines, before a howling electric guitar is met by an eruption of squealing synths. It’s more synth-punk than the Units, let alone Devo, its sonic combustibility invoking the old world in battle with the new. Yet Shelley’s lyric refuses the cosiness of a falsely remembered past (“woolly dreams”) and memory’s function as Stockholm syndrome (“even though [the past] wasn’t so good/ It was all that I had”). But delivered in his characteristically anxious yelp, the song has no faith in the future (“tomorrow’s just another day”). Again, thanks to Dare – alongside Depeche Mode and Soft Cell – synths would soon lose their ‘futurist’ association, and bespeak ‘the present’, and in retrospect ‘the 80s’.

Equally apposite to its historical moment is ‘Guess I Must Have Been in Love With Myself’, with its synthwash and chugging beat, while being slavered in acoustic and electric guitars. A Flock Of Seagulls would produce a toned-down version of this sound within months. While inexplicably never a single, ‘Guess I Must’ features a melody as big as any 80s pop hit, but clearly articulates the anxiety repressed in the era’s neurotic positivity. “The rate of change is a sign of the times” Shelley frets as the huge chorus builds up to the title line, “I had no time for anyone else/ Guess I must have been in love with myself”. It’s a prescient sentiment for the coming era, underlined by Shelley adopting uncharacteristically butch tones. The closer, ‘It’s Hard Enough Knowing’ is a rock ballad for synths, with Rushent – a former drummer as well as an engineer for ELP, Gentle Giant and Groundhogs – programming 70s rock tom-fills for 80s drum machines. The track manages to be both ominous and cheeky simultaneously, predicting the decade’s domination by the power ballad, while suggesting another road not travelled, with its bolero section and hints of Led Zep’s ‘Kashmir’ contrasting with the show tune fussiness of 80s power balladry.

If nothing else quite hits these heights, a series of minor pleasures round out the album. ‘I Generate A Feeling’ is another oblique comment on the conjuncture, a utopian love song couched in dystopian Man Machine language – “I am recharged with energy from down below” and culminating in “I just reach deep inside and switch on my euphoria”. Musically it’s matched by gaseous Travelogue synths being spliced with thrashing Bowie-esque 12-string. ‘I Don’t Know What It Is’ matches more Human League synths to ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ piano and Iggy Pop-esque vocals, its attestation of emotional intensity in stark contrast to 80s’ attestations of indifference (from ‘Love Is A Stranger’ to ‘What’s Love Got To Do With It’). The only weak track, ‘Just One Of Those Affairs’ is the synth pop 12-bar boogie no-one needed, but curiously preminiscent of Girls Aloud’s ‘Biology’ it still manages to put the past and future in dialogue. Still it’s a strange inclusion when the rockier B-sides added to the US album – and included on this reissue – are far better, notably ‘Love In Vain’ whose punch-drunk soar is hampered in the nicest way by Shelley’s vocal limitations. The 12-string driven ‘Maxine’ is folk-rock backed by cracking machine beats.

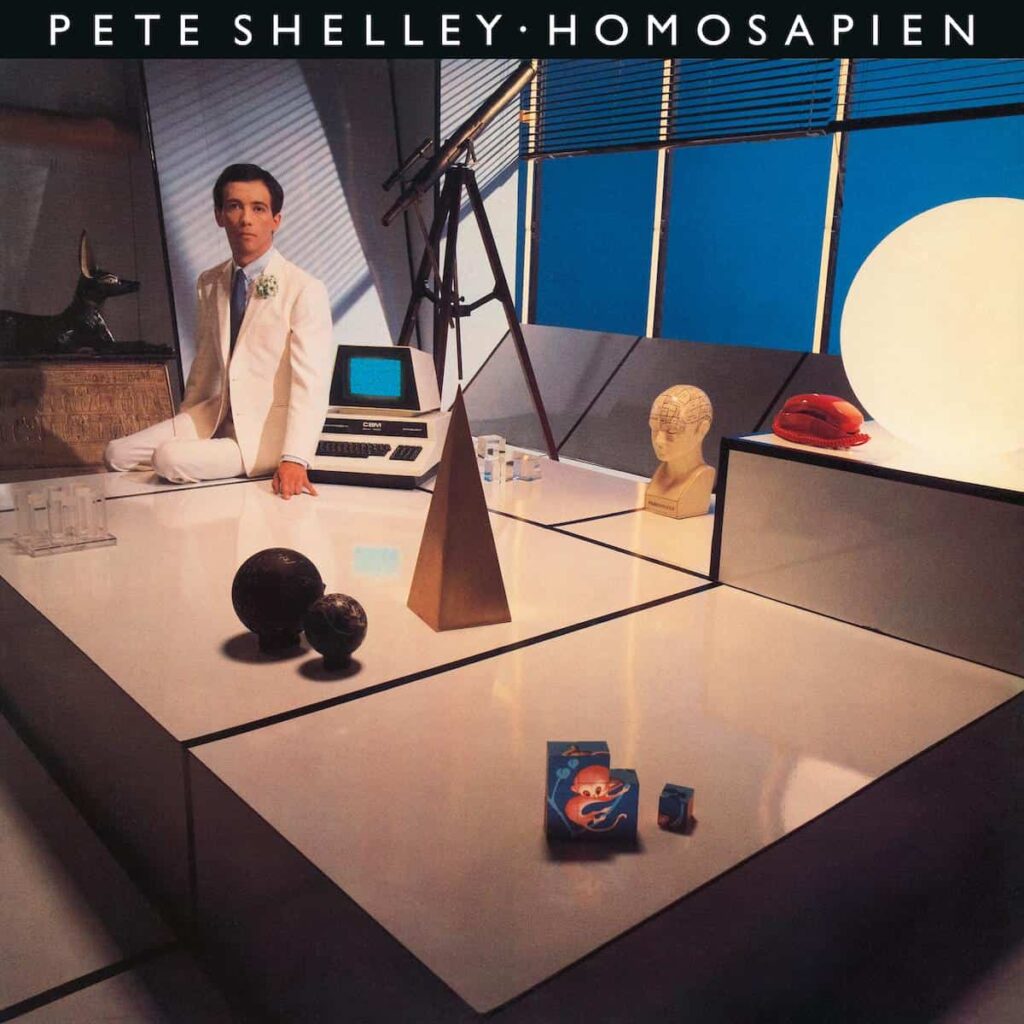

Best of all, ‘Witness The Change’ boasts as lush a production as anything on Dare, and as strong a melody, while its opening lines provide an unintended commentary on Homosapien itself: “In my mind there are mirrors/ Reflecting on the past/ The shattered hopes and dreams of a future/ That was never meant to last.” Homosapien’s cover presents the once styleless Shelley in a natty white suit in a super-stylised office, computer console at his side, but the effect is less ‘80s’ than sci-fi. It’s entirely fitting to an album that’s an irresistible document of a future that never transpired.