If you look at Nico’s artist page on streaming sites, are you going to see ‘Valley Of The Kings’ in the list of her top songs? ‘The Sphinx’? ‘Ari’s Song’? The answer is no (although it should be yes) – but, as the years pass, the vitality and unparalleled austere beauty of Nico’s solo records continues to attract listeners both new and old. Domino’s reissues of 1968’s The Marble Index and 1970’s Desertshore – her second and third LPs but the first records of her own material – are worthy reminders that the essence of Nico, while hard to pin down for someone so inscrutable, lies in her own compositions, her own melodies, singing her strange, beautiful songs in her own voice – literally and figuratively.

Nico’s background as a German fashion model, Warhol muse, and member-but-kind-of-not-a-member of The Velvet Underground has informed the public discourse on her since the 1960s. In her latter years, her constant cycle of touring dingy clubs around Europe with her band primarily to fund her heroin habit (there were tales of posting heroin between hotels) became a sad bookend to an enigmatic, itinerant life. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the cultural concept of “Nico” had often been informed by the people, and specifically men, around her – the Lou Reed songs she sang with The Velvets, her solo debut Chelsea Girl (1967) which contains songs by Dylan, Jackson Browne, and Tim Hardin, her appearances in films by Warhol, Morrissey, and Fellini. But it is her solo work, particularly the trilogy of records she made with John Cale in the late 1960s and early 1970s, that is the key to getting closer to whatever the ‘real’ Nico might be. And on these occasions – and particularly on Desertshore – Cale was less director and more facilitator for the sheer majesty of Nico’s vision – which is front and centre.

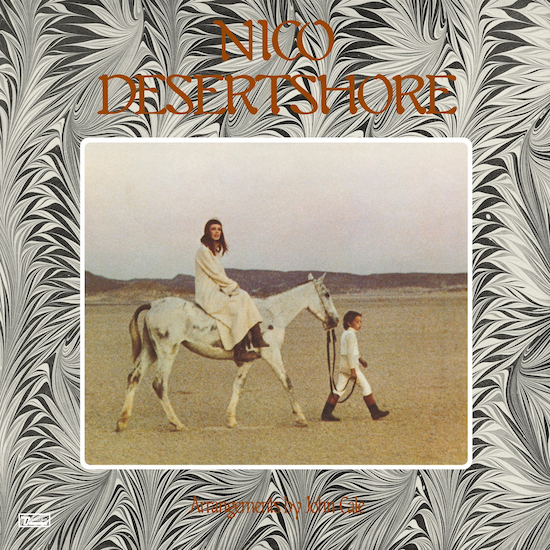

Recorded in the space of around three days, Desertshore is arguably the crowning achievement of her solo career, teaming her up once again with Cale as arranger and fellow musician, plus Joe Boyd, fresh from working with Nick Drake and The Incredible String Band, as de facto producer. Some of the material had also been conceived as part of Nico’s collaboration with the French filmmaker Philippe Garrel, with whom she had begun living in Paris’ Montparnasse Hotel in a black-painted room devoid of heating and electricity. His film featuring her, La Cicatrice Interieure (The Inner Scar) was filmed in the deserts of Egpyt and America; a still appears as the cover image for the album.

Buoyed by this burgeoning creativity, Nico approached Desertshore as a composer. Its songs are keyed in descending minors, like a traditional German song cycle (a methodology she would employ again on 1974’s open crypt of an album The End). As such, the songs feel like you’re slowly descending into some kind of abyss, but curiously with Desertshore there are flashes of light on the trip down – the warm palette of trumpet on the hymnal ‘My Only Child’, for instance, which also contains, unusually for Nico, gentle vocal harmonies; or the mournful ballad ‘Afraid’.

On the diligence of her song craft, though, she once lamented: “I don’t think anyone cares about these things.”

But it is the songs – and Nico’s very craft – that dominates the mood. On the previous LP, The Marble Index, Cale would sometimes bottom out Nico’s harmonium and fill the arrangements with icy neo-classical instrumentation; there would be chiming glockenspiels like black ice cubes, the piercing dolour of the bosun pipe cutting through sea-fog, clattering pianos like slamming doors against the creaking of Nico’s pneumatic harmonium drone.

On Desertshore, though, you think first of the songs – the melodies, the harmonium, her voice – not the arrangements. Cale gives Nico’s songs room to do what they need to, because they don’t need anything else. ‘Janitor Of Lunacy’ features no arrangement at all beyond Nico’s harmonium – gloriously, beautifully, luminously sad and sombre. Where he does add textures and tones – the percussion in ‘Mütterlein’ that gives the song its funereal processional feel, the swirling, murky landscape of ‘All That Is My Own’ billowing like desert sands in the wind, the scraping violas in ‘Abschied’ that underpin the groaning organ – it’s always to complement what is already there, to bring out the tones within the music. It’s never to compensate, or to couch.

The Marble Index was proclaimed by Lester Bangs as “the greatest piece of ‘avant-garde classical’ ‘serious’ music of the last half of the 20th century” and by Richard Williams in Melody Maker as “one of those records which just might, in 10 or 20 years’ time, be regarded as some sort of milestone… desolate and wind-blown, scarred yet futuristic.” It is a sub-half hour of utterly stark beauty and sometimes brooding menace, as dark and icy as the album cover, and its core simplicity – listen to the two-chord seesaw drone of ‘Lawns Of Dawns’ – embellished by Cale’s arrangements that draw out the “implied core” of the music.

Desertshore, recorded a year or so on and released in December 1970, represents a confident step forward in Nico’s writing and performance. If The Marble Index was the first burst of her creativity – and the sublime melancholy of songs like ‘Frozen Warnings’, ‘No One Is There’, and the terrifying ‘Evening Of Light’ cannot be denied – then Desertshore is where it blooms. So potent is the writing that Cale’s arrangements are simply supplementary; there are those aforementioned trumpets and choirs that lend the songs a vague warmth as opposed to the wintry dreamscape of The Marble Index, but the core – and not an implied one this time – is always Nico’s voice and harmonium.

Nico’s deployment of the harmonium is key to understanding the off-kilter energy of her music; she was inspired by Ornette Coleman to flip music theory and instead play the melody in the bass with her left hand. As a result, many of her songs have a keening, queasy quality in the upper register, with the melodies striking in their bold, deep minimalism in the lower register. The harmonium wheeze of ‘Janitor Of Lunacy’, which opens the album, sounds like a door has opened onto the barren desert of the album cover; it is medieval in its primal starkness and earthy in its longing. While Nico’s lyrics err on the esoteric side (“Janitor of tyranny / testify my vanity / mortalise my memory / deceive the Devil’s deed”), the song had been inspired by the death of Brian Jones and one doesn’t need to take the lyrics literally to feel the emotion in her voice.

Emotion is at the heart of Desertshore. Nico traded the rococo Wordsworthian romanticism of The Marble Index for the language of Germanic folklore – there are lyrical allusions to castles, falconers, and knights, to forests, bitter wine, cradles, and tombs. Two songs, the excoriating ‘Abschied’ and relentlessly oppressive dirge ‘Mütterlein’ (written after the death of her mother Grete in February 1970), are sung in her native German. Her young son, Ari, appears on the chilling lullaby ‘Le Petit Chevalier’ (if you listen very closely, you can hear Nico off-mic encouraging him with the next line). As such, Desertshore is Nico’s most personal album, her “heimat” album, the album that one feels is closest to the core of her creativity.

Listening to the solo demos collected on the 2007 retrospective The Frozen Borderline is an interesting exercise, as one can hear not just the crack of emotion in her voice on the demo for the propulsive ‘All That Is My Own’ and the original harmonium accompaniment for ‘Afraid’ and ‘My Only Child’, but also the increased sophistication and complexity in the writing. Cale himself attested: “Her singing was more confident, and I was surprised to hear how her songs had become more musically coherent. The melodies became more adventurous; beautifully constructed, too. She focused much better on having subtle, simple lines and shorter phrases. And she started writing changes – contrasting sections, even.”

One such example is ‘The Falconer’, which begins as a sombre mood piece (and one in which Nico employs effective use of space and silence) before moving into a melodic section that one may even describe as pretty. One imagines the falcon released, free, flying. Pretty is also a word befitting the choral elegance of ‘My Only Child’; there is a lightness of touch and spring in the melody that is absent from much of Nico’s other material. ‘Afraid’, meanwhile, is stunning – a stylish, sad torch ballad that eschews literary allusion for direct address – “have someone else’s will as your own / you are beautiful and you are alone,” she sings to Cale’s elegiac piano accompaniment. Nico’s voice was once memorably described as like “a Garbo-voiced IBM computer falling out of a window”; a song like ‘Afraid’, where she employs a softer and breathier technique, showcases her versatility compared with, say, ‘Janitor Of Lunacy’ or ‘All That Is My Own’, where she richly elongates lines, or the heavy vibrato in ‘Abschied’, or the melismatic syllable-mangling of ‘The Falconer’. Her voice, frankly, is a thing of beauty.

Desertshore threatened to bring Nico a little further into mainstream focus – a promotional push in early 1971 saw her deliver a stirring Peel Session, an exquisite TV performance of ‘Janitor Of Lunacy’ and ‘The Falconer’, and a gig at the Camden Roundhouse. The album made waves of a kind at Rolling Stone (“guttering candles sputtering black wax on cold stone floors as the sound of Nico’s harmonium drifts in from another room. It doesn’t have a beat and you can’t dance to it”) and Melody Maker (“a mediaeval ruin of a record”), and gigs were booked for New York’s Gaslight club in the spring of 1971. However, her increased dependence on heroin and decreased reliability led more often than not to various missed opportunities in the ensuing years. She followed Desertshore four years later with a final album in the ‘Cale trilogy’, The End, which is perhaps the most oppressive of them all, bolstering Nico’s creaking harmonium with Roxy-accented synths and sound effects. From then on, her life and career became a roving one, moving between continents and sporadic recording contracts until she settled in Manchester in the early 1980s and began her wearying road dog lifestyle that continued until her untimely death on Ibiza in 1988.

One may look at Nico’s discography as a whole and see an artist who stuck to her guns, who embraced her individuality, and who cared only for the creativity of the moment. Nico simply couldn’t be arsed to play the game and what was important to her musically was satisfying the root of her creative spark – that is what makes her records so unique and such an ‘experience’. They are all worthy and all beautiful, but Desertshore sneaks atop the turrets with its focus and intensity, its purity of vision, and its variety in mood. My only gripe is that the peerless ‘König’, also recorded during the album sessions, was left off the record. (It later appeared, in re-recorded form in Nico’s even-deeper voice on 1985’s Camera Obscura.) It possesses one of her most beautiful melodies, and the throb of emotion in her German language singing, the way the vowel sounds wrap so acutely around her solemn harmonium, is something special and unique to hear.

Cale was right when he said in 2015 that this music was “truly unprecedented”. Nico herself said: “I want to go beyond history. My songs are visionary.” Both of them are on the money. Desertshore is the kind of record that could have been made today, fifty years ago, or in a distant century. Its arcane beauty continues to marvel – set aside an uninterrupted half-hour and go for it.

Desertshore and The Marble Index are reissued by Domino today