David Crosby once accused Neil Young of being the most self-centred, self-obsessed and selfish person he knew. "He only thinks about Neil, period," elaborated the moustachioed one. "That’s the only person he’ll consider. Ever!"

If there wasn’t some element of psychological projection occurring there (given that Crosby had his own share of personality quirks, if you like), it was an unfair exaggeration. As irredeemably flawed human beings we can find it naturally easier to empathise with those who are directly in front of us rather than others who might be situated halfway around the world. That doesn’t make loving actions moot. To pick an obvious example, Young cares about his children. And others’ too. Millions of dollars have been raised over the years for The Bridge School, for instance.

That being said, one thing Neil Young really does think about frequently, and perhaps spends more time worrying about than anything else, is putting out more music by Neil Young. New studio albums. Old archive recordings. An album with this backing band. Another with that backing band. A live double-LP here. A concept album there. Soundtracks every now and again. It’s relentless.

There’s even a theory that there are members of the baby boomer generation who abandoned their earlier flower power idealism in favour of adhering to the neoliberal rat race for the sole purpose of securing an annual income substantial enough to guarantee the purchase of everything that Neil Young puts out. Plus merch!

That’s not Neil Young’s fault. It’s one consequence of the man’s inexhaustible prolificacy. Which comes from where, exactly? His father, Scott, worked as a journalist, sportswriter and novelist who, according to Wikipedia, produced 45 books in his lifetime. All those hours. All those pages. All that ink. All those thousands and thousands of words. Mourning his friend Martin Amis who died earlier this year, Salman Rushdie wrote this for The New Yorker: "He used to say that what he wanted to do was leave behind a shelf of books — to be able to say, ‘From here to here, it’s me.’ His voice is silent now. His friends will miss him terribly. But we have the shelf." The shelf left behind by Scott Young is impressive but have you ever seen those owned by collectors of his son’s output? Shelf upon shelf upon reinforced shelf, heaving under the weight of CDs, LPs, boxed sets, "official bootlegs" and bootleg bootlegs.

Writers gotta write.

"My boss is my muse," Young has offered as an explanation and he follows this in whatever direction(s) it takes him. Another reason provided is that he is prone to spending money as soon as he earns it, is bad at saving it up, and has to put stuff out and go on tour to stay in the black. If there’s ever been anyone in Young’s team who’s raised the potential problem of oversaturating the market with his produce, then presumably they’ve long since been booted or learned to hold their tongue.

There is more to it than that, however. What makes a great artist, as opposed to a hobbyist or the half-hearted superstar who heaves themselves off the chaise longue every so often for a reunion tour to pay for the house extension/divorce agreement/kids’ school fees? True artists have an irrepressible desire to make art and to spend their every waking moment on fulfilling this mission. Painters in their studios. Writers at their keyboards. Architects at their drawing boards. Even when breaking to refuel, make hanky-panky, work a side-gig to pay the rent or spend time doing something their agent or manager tells them to do, their minds will be on the more pressing concern of THE LIFE’S WORK.

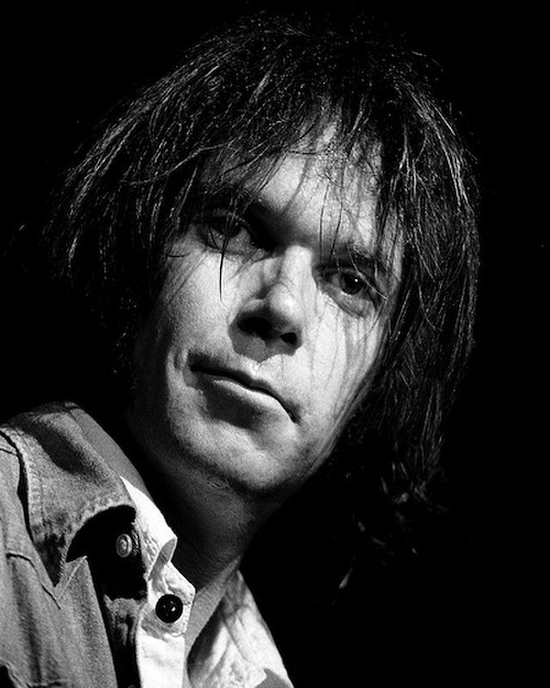

Neil Young in 1976, photo by Mark Estabrook via Wikimedia Commons

That’s how the artistic psyche works, even if not all that it produces is necessarily presented to the public. Not even Young does that. He’s been known to abandon albums on impulse (or rather that of his governing "muse"), sometimes releasing the recordings years or decades later as part of his long-running and apparently never-ending Archives project.

In the now-infamous episode of Friday Night, Saturday Morning in which John Cleese and Michael Palin had to defend the allegedly blasphemous feature film Monty Python’s Life Of Brian, they were confronted by a sour-faced Bishop of Southwark and Malcolm Muggeridge. Then 76, the ex-editor of Punch had converted to Protestantism a decade prior. During the tense debate, Muggeridge made some outrageous claims regarding "the story of The Incarnation" and how it has inspired every great artist, writer, composer, builder and architect who ever lived. He forgets that other countries, cultures and religion also exist as part of the planet’s "civilisation", as Cleese points out. Furthermore, Muggeridge neglects the issue of where artists in Christendom had to find their commissions. The church had money. Ergo religious painting paid off. Whether or not they believe in the harp-heavy place in the clouds, and be their patrons the church, monarch, Napoleon Bonaparte, Warner Brothers Records or Charles Saatchi, artists like to make a living from their talent and a significant impetus for them to express themselves in their chosen field is that burning need to say "I WAS HERE."

If that sounds self-centred, self-obsessed or selfish, there are worse ways for a mortal to spend their brief time on Earth. Like arms dealing, for instance, or advertising gambling companies.

Ever noticed how music journalists keep projecting onto their subjects the presumed motivation of an impending death? When Bruce Springsteen brought his recent tour to the UK, reviewers couldn’t resist evoking the grim reaper. Granted, The Boss looked older. Just as we all do. Always. He talked about friends he’d lost, as well. I don’t (or choose not to) believe Bruce was signing off, saying goodbye or staring into the approaching void in front of his audiences. After postponing some dates due to illness, he extended his tour dates further. Reports of his death have been greatly exaggerated.

When Bob Dylan released Time Out Of Mind in 1997 several reviewers heard it as the sound of Mr Zimmerman feeling old, ill, frail and bracing himself for the shuffle off this mortal coil. He was only 56! He’s made another ten albums since. With hindsight, Johnny Cash was said to have "written his own epitaph" with the song ‘Hurt’ which is daft because he didn’t write it, was told to cover the Nine Inch Nails number by his producer Rick Rubin, and Cash continued recording thereafter. The lyrics have little if anything to do with Cash’s life and work.

Is this the reception that will also greet Neil Young’s new album, which features acoustic and stripped-back solo performances of songs dating back throughout his catalogue? Is that fair? Is that what he is doing here? Is that new?

This morbid theme is imposed on ageing musicians as if it’s a fresh thought that occurs to these figures only from middle age (or later). Mortality grows more pressing, certainly, as life rattles on at an increasingly chilling pace. Yet in all likelihood, it was always on their minds. Woody Allen says he’s understood the concept of death since the age of five and found the idea so unfair that he hasn’t been happy since. He begins the script of his next film as soon as he’s finished editing of the last one.

Since his debut album, Springsteen’s repertoire has been packed with songs, many of their verses written in the past tense and looking backwards, about getting older. And older. And then older still.

Neil Young is the same. As a young man he wrote ‘Old Man’, noting the often overlooked commonality between those of different generations. "As you are now, so once was I," the older person in the narrative could be imparting to his younger observer. "As I am now, so you must be…" Elsewhere on the Harvest album, Young sang straightforwardly of "getting old." He was still in his twenties.

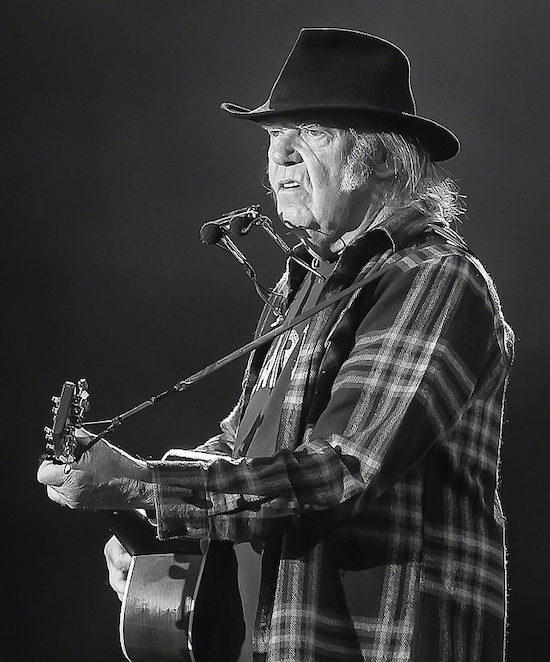

Neil Young in 2016, photo via Tore Sætre via Wikimedia Commons

He has never been a pious man. As a child, Young longed to stop being taken to Sunday School. He says he viewed religion with outright hatred for a very long time. The song ‘Timberline’, from the Toast album, empathises with a logger’s loss of faith. 2005’s ‘When God Made Me’ can be read as a satire on the arrogance of belief. Young has described his own spirituality as closer in line to those of pagans or Native Americans. His church, he says, is to be found in forests, fields, rivers and oceans. It is the earth to which he will one day return.

Young has spoken of taking stock and feeling more vulnerable following the brain aneurysm he suffered in 2005. It isn’t as if his career can be tidily divided into its pre-aneurysm and post-aneurysm periods, however. He doesn’t seem to have radically altered his approach to churning out material, old and new. He carried on as before.

It wasn’t the first shock to his body in the whole of his life. The oldest song on Before And After is ‘Burned’, originally from Buffalo Springfield’s debut album of 1966. People used to believe its lyrics described coming down from drugs. It was actually about one of Young’s epileptic seizures. "No use running away, and there’s no time left to stay," he sings. "… No time left and I know I’m losing." ‘Mr. Soul’, which also appears here, was written after a seizure too. This one occurred while Young was onstage with the band. Some of their audience believed it was part of the act.

The songs on this album are presented without gaps, intended as one "uninterrupted 48-minute piece", and each number, many of which are not among Young’s better-known hits, has been selected for a reason. "Love" comes up a lot across the lyrics, as does the word "dream", which life is but a… "When you’re dying and you could be living," the singer advises on the final song, "don’t forget love."

What is Young telling us on Before And After? Taken as part of the entire oeuvre, it is less to do with the fact that he is now, at 78, contemplating the pressing reality of his own mortality and more to do with the fact that this is exactly what he has always done.

Long may he continue.

Neil Young’s Before And After is released on December 8 via Reprise