“I have a habit,” admits Nate Scheible, Washington DC-based composer and musician, “of picking up unlabelled or vaguely labelled cassettes, VHS tapes, reels, even burned CDs, mostly at thrift stores, flea markets, etc. I believe that this one was from a Goodwill in Northern Virginia. It was a cassette just labelled ‘me’. Which is exactly the kind of thing I’m on the lookout for.”

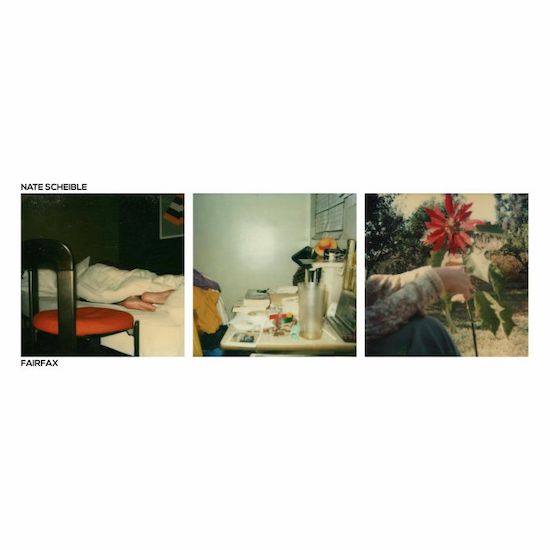

The voice Nate found on that tape – a female voice in the form of phone messages and voicemails to her partner – make the basis of Fairfax, a tape Nate self-released in 2017 that is now receiving a long-needed vinyl and digital reissue by Warm Winters. I haven’t been so moved by a piece of ‘found-sound’ manipulation in my life – what Fairfax achieves isn’t just the lending of ‘dignity’ to detritus, but a beautifully compassionate portrait of love and the foregrounding of this anonymous woman to the point where she becomes the hero of Fairfax, where she becomes as big a character in the listener’s consciousness as the love she’s expressing. Nate, and us, know nothing about this woman beyond what she has left on this tape, but as you listen you find yourself picturing her, deeply empathising with her, walking the same tightrope between hope and desolation she walks so bravely.

It’s that compassion to its source that radiates out of every luminescent moment of Fairfax and that marks it out as different, markedly different, to pieces like Gavin Bryar’s Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet or Steve Reich’s ‘Come Out’. In the case of Reich of course, Val Wilmer’s assertion of Reich’s parochial racist attitudes towards Afro-Americans leaves a nasty exploitative taste in the mouth that has excised ‘Come Out’ from my listening entirely. Bryars’ piece is better, and lends its homeless vocalist a dignity that emerges from his noble optimism and faith. Even there though one wonders whether Bryar’s chopping of a single shard of the man’s voice, folding his inarticulacy in on itself, really provides more than a shallow portrait of hope in the gutter, a reassuringly one-dimensional picture of faith without reason. The use of the woman’s voice on Fairfax is entirely different – Scheible uses much longer passages of her messages, she is allowed to fully express her longings and hopes, while he builds sounds – tones, drones and music – around her expressions in a way that makes the album follow a gorgeous arc of redemption. What comes across crucially is total respect and fondness for the source rather than any kind of ‘playfulness’ or manipulation. I asked Nate what first grabbed him about the tape he found.

“I’ve always been hesitant to use a lot of these found recordings and Fairfax was the first time I decided to integrate one. It’s a gamble, right, because as soon as you introduce text or lyrics, there is a tendency for it to overshadow the music. But with this one, there was so much to draw from that allowed me to weave it through an entire record to complement the music in a way that I was comfortable with. I liked that it was raw, unrehearsed, genuine, and there were more practical considerations that persuaded me to use it as well. The sound quality was good. She spoke very clearly and articulately so that you could understand everything.”

That clarity means that while Scheible can make the music as grainy and refracted as he wishes, the protagonist’s voice remains crystal clear and that gives the work an emotional heft that’s overwhelming. There are hints of darkness on Fairfax’s nine tracks. Although the voice remains non-specific in terms of places, dates and personal details you find listening to this woman’s explanations of her illness, questions to her lover and resolutions to the future rapt with hope, hoping that her and her partner’s problems can resolve because they wrap themselves so tightly around your own memories, losses and heartbreaks.

Throughout, Scheible’s composition is sensitive and responsive to the narrative shifts and impetus. I wonder if Scheible approached Fairfax as if he was composing a soundtrack to the movie of this woman’s life at this particular time in that life. Was that how he pictured her as he wrote?

“I had a very vague picture in my head of what she looked like, what her home looked like, what her partner looked like, etc. Just kind of faint images. But these did not have an influence on the music at all. I probably had about half the music completed before I started integrating the found recording. Then finished the remaining music knowing that a voiceover would be integrated. Contributions from other musicians mostly came near the end – especially as I started thinking about solos or little melodies as their own kind of speaking parts to stand out among what is otherwise mostly ambient, amorphous sound. I don’t have a film background, but I imagine it was a similar process in terms of editing. Especially when trying to craft a narrative and determine the order in which spoken sections appeared. Pacing was important. Making sure the music and text worked in harmony, without one detracting from the other. Trying to keep the music engaging in the gaps between spoken passages.”

There is a deeply cinematic feel of narrative in Fairfax, a journey from unease and fear to final redemption by the genuinely tear-inducing ‘There’s Nothing That Says I Cannot Dream’. ‘Good Morning My Love’ and ‘After Work On Monday Afternoon’ give hints that illness and looming surgery are part of this woman’s story. Sometimes Scheible lets her voice evanesce altogether – ‘Together Again’ wordlessly pitches fuzzy, strung-out chorales against crepuscular peripheral whispers and moans before ‘Our Doubts Are Traitors’ has the voice reading from a self-help manual under unsettlingly dissonant drones. ‘Made To Feel Special’ is the first track on which we get to prominently hear the live instrumentation Scheible has interpolated into the mix – Kyle Farrell’s vibraphone, Maggie Gilmore’s backing vocals and Luke Stewart’s jazzy bass abstractions not only framing the vocal source beautifully but also creating a distinct picture of Fairfax’s creation in Scheible’s studios in DC & Maryland. ‘Thrilled To Death’ hints that the aforementioned surgery is now imminent, but is so lit up with love and caring it’s impossibly poignant even if Scheible’s textures are like Stars Of The Lid at their most haunting. ‘With Any Kind Of Luck’ has a sense of post-operative impetus – the illness is still there but the need in her voice, her yearning to be reunited with her lover, her upset at his anger, the faint hints of tears in the grain of her voice lend every single phrase an emotional wallop that’s irresistible, only accentuated by Sarah Hughes plangent sax-lines. On the closer, the devastating ‘There’s Nothing That Says I Cannot Dream’ Scheible actually fades her slowly out over the building bed of glimmering sound, leaving us in no doubt that this woman is a hero, has a future, has hope. It’s her story that emerges triumphant, with Scheible occupying a fascinating non-persona of someone who is both listening to her – as are we – but who is also providing the soundtrack to her story.

I have to ask Scheible, did that story, that curvature of the narrative, emerge by design or by accident?

“I didn’t put together a story or narrative that stood on its own and then set out to score the music under it. It all came together simultaneously. Sometimes I’d start in on a piece of music and that would dictate what words would go over the top and sometimes it was the opposite. In cases where I set out to create music to incorporate speaking parts, it was mostly in the form of how the specific musical section would be structured more than anything, with one exception. At the end of ‘Together Again (Reprise)’ there’s this weird sample I found of an instrumental part of some self-help tape. It was a cheap copy of the tape that had obviously been redubbed multiple times. It sounds like at one point somebody was in a yard somewhere at night, crickets chirping, and just stuck a mic up to a boombox to record a copy of it – getting both the ambience of the outdoors along with the contents of the tape. I only included that little section because it brought to my mind a certain image. Not of her making the tape, but of her just sitting in a lawn chair in her backyard late one summer night, just thinking…”

This I think is key to why Fairfax works. Scheible doesn’t smother the source with ‘empathetic’ sounds – he sensitively gives her space to speak, to the point where it stops feeling as if the music is composed at all – rather that it naturally emanates as a backdrop to the voice’s suggestions and trajectory. And by almost disappearing himself from the process, Scheible gives both the nameless source, and his own sensitively orchestrated work a place to co-exist, blend and support each other. ‘Fairfax’ will engross you as a listener as much as it clearly engrossed Scheible: you do find yourself – not only because of the warmth of the voice, but the beautifully faltering way it gains self-realisation – rooting for this woman desperately, emotionally bound up in the traces she has left on the tape Nate found in the Goodwill. Built from an ad hoc, accidental encounter with a lost love-story, Scheible’s Fairfax attains the weight of tragedy, of an epic, and remains a testament to the human spirit that’s impossible to resist, an album that crafts a story bereft of sentiment but a story that’s overflowing with heart and hope. A story that is so needed right now, a story that arms the soul. An essential, miraculous release.