“Punk rock is a word used by dilettantes and heartless manipulators about music,” says an exasperated Iggy Pop as Mogwai’s restrained guitars chime underneath his words. “It’s a term that’s based on fashion, style, elitism, satanism, and everything that’s rotten about rock & roll.”

‘Punk Rock’, the opening track on Mogwai’s second album Come On Die Young samples part of a conversation between the musician and Canadian broadcaster Peter Gzowski which aired on CBC’s late night talk show 90 Minutes in 1977. Both sound ill at ease during the segment, which had been hastily arranged after union the American Federation Of Musicians scuppered an appearance by Iggy Pop and his band – featuring David Bowie on keyboards – at the eleventh hour. The glib presenter asks the defensive musician if he will explain punk rock, and Iggy Pop duly obliges: “You see what sounds to you like a big load of trashy old noise is in fact the brilliant music of a genius: myself. And that music is so powerful that it’s quite beyond my control.”

Powerful music beyond one’s control could easily be Mogwai’s MO – the "young men who give what they have to it", as Iggy Pop put it. And it’s easy to see why the band – forging their own feral path in the late 90s amid the cultural hollowness soundtracking New Labour and the crossover with the flabby arse-end of Britpop – would want to align themselves to this notion: the nihilism of punk. Iggy Pop leaves us with a question: “Do you understand what I’m saying, sir?” During Mogwai’s formative years there was a palpable sense that they were frustrated at being misunderstood in a culture that they were kicking back at, as they themselves sought to understand the band they were and the band they would become.

Of course the band they would later become were to be chart toppers. But – 25 years after the release of Young Team – how did we get to that point? Mogwai’s transformation from snotty upstarts and provocateurs to elder statesmen makes listening back to their first two albums from the vantage point of 2023 a surreal experience. I say with deliberate and pronounced understatement that in the late 90s it would have been very hard to listen to the loud, brutal (though beautiful) music the band were making and imagine that two decades later they would be celebrating an album called As The Love Continues reaching the top spot.

First we need to go back to 21 October, 1997, the day Young Team was released in a dark swirl of righteous noise, Kappa tracksuits and tinnitus-inducing feedback. The Verve’s Urban Hymns was at the top of the charts, having ousted the best-selling album of the year, Be Here Now. But theirs was not the "utopianism" of ‘Live Forever’, theirs was the "nihilism" of Come On Die Young – the stranded youngsters giving a cheery middle finger to the Britpop procession going by.

Young Team reached number 75 in the album charts. 1999’s Come On Die Young would reach the dizzying heights of 29. But these albums weren’t made to scale the charts: the band back then were relatively uncommercial and existed in a different space to the vacant realm of Britpop. Braithwaite, wrote in his recent memoir Spaceships Over Glasgow, that Britpop was “the complete antithesis of everything we cared for. It lacked imagination, beauty and scope” and the band were determined to distance themselves from what else was going on, whether it be Britpop or the seriousness of the post rock movement (a phrase they despised) and the Slint comparisons which were constant and unavoidable.

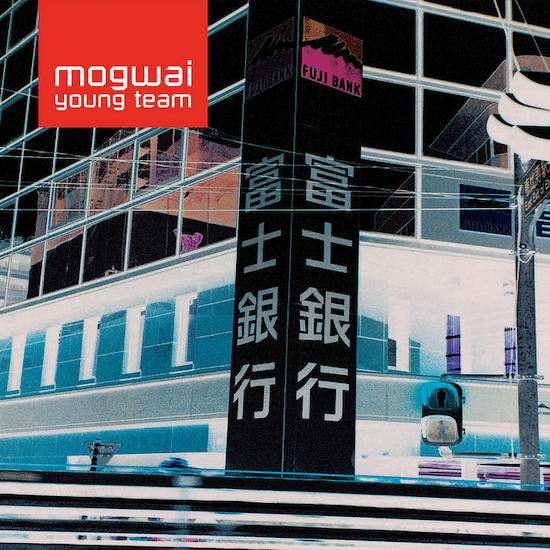

The band used every means available to create a psychic world which stood in stark contrast to what the cultural mainstream was offering. Their song titles (‘Punk Rock/Puff Daddy/ANʇICHRISʇ’); the Exorcist-inspired album artwork of CODY; then-member Brendan O’Hare’s photograph of a Fuji Bank in Shibuya, Tokyo for Young Team; their US underground-facing and heavy metal-literate sound which, in a guitar context, couldn’t have been much further away from the standard mod-Small Faces, or rocker-Slade obsessions of the day; even their pseudonyms (pLasmatroN, Cpt. Meat, bionic, DEMONIC, +the relic+) show a knack for counterintuitive thinking and magical world building.

This was not a band taking its cues from Quadrophenia, The Kinks and merrie England. Like fellow countrymen, Arab Strap, they celebrated their contemporary Scottishness in an iconoclastic manner, something unusual enough for the day. (This needs some qualification: it wasn’t the Scotland of Irvine Welsh and Primal Scream, figures who had come of age during punk, but a street-level Glasgow and Falkirk of the late 90s.) Both album titles, referring to gang names, reflected this, something saying more about the psychic space they were trying to create rather than the quotidian reality of their lives. Braithwaite, in his memoir, found this misunderstanding amusing in retrospect: "We met quite a few hairy characters who obviously thought we were serious… you’ve got all these maddies coming to see this instrumental art-rock band."

But as obtuse and weird as some of these references might have felt, it was all unpretentiously undercut by their dark humour. Indeed, it was the depth that went alongside this disorganised playfulness that was the trick – the press may have tried to peg the band as Kappa-wearing misfits picking fights with indie big hitters and smuggling vodka across Europe in condoms but you could feel the weight of the world they were trying to create reverberating through each song.

It is there in the words of Young Team’s opener ‘Yes! I Am A Long Way From Home’. Friend of the band Mari Myren reads from a Mogwai live review published in a Bergen student newspaper: "Music is bigger than words and louder than pictures." But despite the knowing hyperbole it feels now like a reminder of how the band challenged the received wisdom of what instrumental music could convey in terms of ideas and message, as well as capturing something core to their ethos, something that would remain in place throughout their career.

In More Brilliant Than The Sun, writer and artist Kodwo Eshun talks about how the lack of lyrics in techno is what makes it more meaningful, or helps unlock deeper layers of meaning at least: “As soon as you have music with no words everything else becomes more crucial; the label, the sleeve, the picture on the cover, the picture on the back, the titles. All these become the jump off points for your route through the music." All of these things apply to what Mogwai were doing on their first two albums; they had an identity and an ethos and the lack of lyrics in many ways added to, rather than subtracted from, the symbolic power of these records.

If that all sounds incredibly serious, this was never a po-faced experiment: the pseudonyms, the song titles (I always loved that they have a song named after Scottish referee Hugh Dallas which you can find on the deluxe issue of CODY) and the liner notes featuring the words: “mogwai wear kappa clothing” helped add a sense of levity, going some way to balance out the solemnity of the music. And the incendiary – and, in those early days, very often chaotic – live shows obviously added an extra dimension to what they were doing. It was the thought that they had put into their world building that helped the music envelop you. It wasn’t empty bluster, their whole aesthetic demonstrated where they were from, what they were about and what they were rejecting. They had been building this world before Young Team of course. They were highly prolific in their formative years: in the 18 months preceding the debut’s arrival, there had been three critically acclaimed singles, an EP and the Ten Rapid singles collection.

But this race to create and world build also revealed that they were still finding themselves, still searching for new ideas and for who they actually were. "We had three different types of songs when we started out," recalls Braithwaite with self-deprecating charm. "We had some vaguely happy songs, but they were shite. We had these really bad grungy songs – these gothy, Joy Division-y kind of songs with my awful lyrics – and then we had these instrumental kind of sad ones without any lyrics. And they were what we felt most proud of, I suppose.” Young Team saw them refining those sad songs and carving out a path to the sound they wanted. It was a brutal and unapologetic debut, more ‘rock’ than ‘post’. It’s full of tension and ear-splitting release; ‘Like Herod’ and ‘Mogwai Fear Satan’ remain some of the best things they’ve ever done: the way they erupt still startles.

But the clear and distinct stylistic shift between album one and two demonstrated they were still exploring. Unwilling to settle into the loud/quiet pigeonhole the music press had lumbered them with, Come On Die Young found beauty in restraint. It was as much about the space left unfilled as it was about what you can actually hear. “There were a lot of ideas on the first record; it was overloaded with them. So we decided to be a bit more subtle,” Braithwaite explained. “It’s the difference between how fast you ride your bike and how slow you ride it — it’s always harder to ride your bike slow.”

Instead, the record simmers menacingly, getting progressively louder, as if they were allowing themselves more slack on the leash as the album progresses. It was as if they felt they had to earn the volume. And you feel that when ‘Christmas Steps’ erupts, its rhythm almost dances as the guitars pound you in the face.

Where did this discipline come from? For that we may find clues in the chaotic and frenetic tours they went on – being on the road saw them eating baby food and snorting so much alcohol on a ferry to Norway that they were genuinely not sure whether one of them had fallen overboard. One show in particular – the final date of a tour with Arab Strap at London’s The Garage in 1997 (before Young Team had even been released) also stands out. I’ll leave Braithwaite to explain: “I recall us playing ‘Yes! I Am A Long Way From Home’ and a certain band member playing the wrong chords and shrugging as he seemed to think/know that it didn’t matter. That same individual slept in a sandpit behind the venue that night. I think Brendan got naked at some point and we destroyed most of our gear and handed it out to the crowd.”

It sounds like quite the night – but the fallout seems to have been pivotal. “In our minds we’d become some bizarre crossbreed somewhere between Butthole Surfers and Led Zeppelin. How I wish that really was the case.”

This epiphany of sorts – the realisation that they were not just there to overwhelm with volume (and take loads of drugs); that they needed to get away, focus on the music and be somewhere free from distraction helped shape Come On Die Young. So rather than head back to the Chem19 studios they travelled to rural Cassadaga, NY, to record with Dave Fridmann. The pseudonyms were the first against the wall – this was now the music of Stuart, Dominic, John, and Martin.

Come On Die Young was a serious and conscious effort to move on – to push and pull and probe at their sound and to create affect by less obvious means. We even got Braithwaite’s up-front vocal performance on ‘Cody’, a beautiful melancholic ballad for old friends. “And the way that it is, I could leave it all/ And I ask myself, would you care at all?” This is the clearest signpost to the Mogwai of today. It felt like a serious band making a serious record. Although, elsewhere, perhaps not too serious. 1999 would also see the Blur: are shite T-shirts unveiled at T In The Park.

And now we’re here in 2023: Iggy Pop a national treasure on 6 Music and Mogwai themselves never far from constant rotation on the same station. And it all seems to make sense, somehow. Iggy Pop’s full reply to Gzowski contained a sentiment which didn’t make it onto the Mogwai debut: “I’ve worked very hard for a very long time to try and make something that’s beautiful enough so that I can enjoy it and so other people can enjoy it.” And Mogwai too put in the work to discover their sound, to find the beauty amid the nihilism.